Recently, I went on a design adventure. I descended into a kinky thing – a fetishistic underworld of little bits of printed paper people licked. Yeah, stamps. Or, perhaps I should say that I took up a philatelic habit. (Briefly.) It sounds so much more clandestine that way. Which is entirely appropriate. Even devoted philatelists don’t go around announcing their predilection. It’s like a secret society of foot fetishists: Only fellow philatelists completely sympathize with the obsession.

How I found myself in this underworld is innocent. I was thinking about the perils of post in the modern world. Canada Post is in the throes of survival; home delivery to some postal codes is being phased out. I thought of the endangered postal species – those heroic people who trudge through all weather to drop something through your door.

Letters are like artifacts now. You’re lucky if you get a few Christmas cards, when once they were a part of festive decorations, something to showcase one’s social network. Post was integral to daily life; waiting for it to arrive; the clatter of it dropping through the slot in the door; stamp collecting was a way to travel the world without leaving home. Who cares about them any more?

I went on a little anthropological expedition, mostly when I was in the land of postal birth – Britain. There, stamps are having a revival. In 2016, a £22-million ($40-million) British Postal Museum will open in London. The Royal Philatelic Society of London – the oldest of its kind in the world (established in 1869) – has seen membership rise nearly 25 per cent in the past 10 years, says Frank Walton, incoming president of the Royal, as it calls itself. Next year, the 175th anniversary of the Penny Black, the world’s first stamp, will be marked with several events. Herewith, my not-quite-postage-stamp-sized field notes.

A stamp design is part of national identity

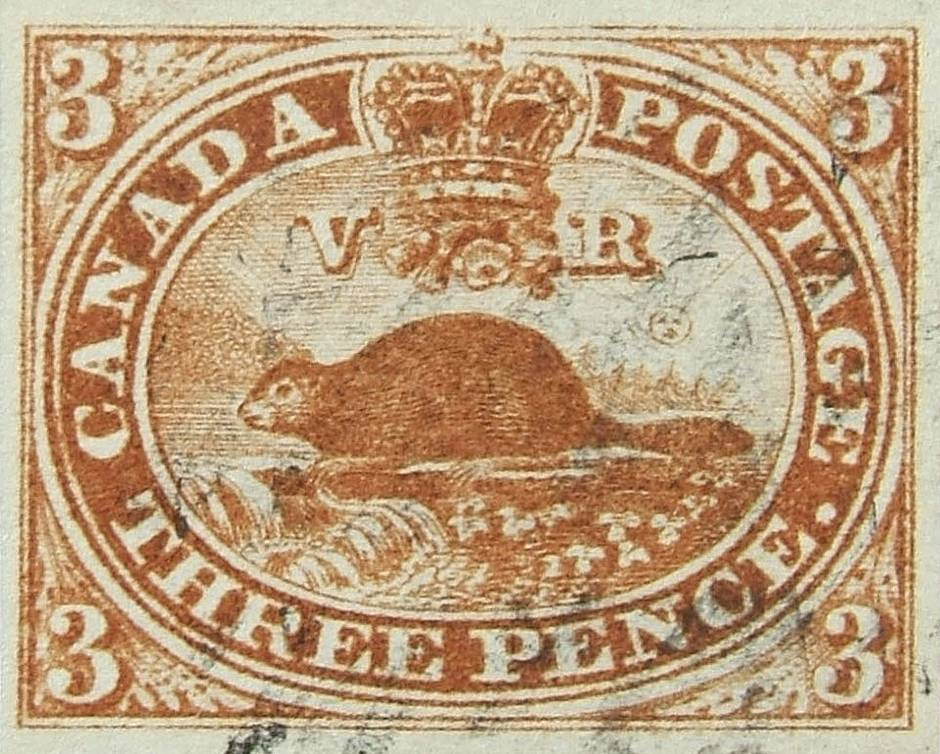

We are a land of beavers. So communicated this country’s first stamp, designed in 1851 by Sandford Fleming, to signify the colony’s economy and the industrious nature of its inhabitants. It’s also a claim to fame in philatelic circles. Canada was the first to put a mammal on a stamp, according to Charles Verge, archivist and director of the Vincent Graves Greene Philatelic Research Foundation in Toronto.

It comes as no surprise to philatelists that China is an area of growing stamp collecting. They’re buying Chinese stamps as a way to repatriate their cultural heritage, one expert explained.

Thingness in a virtual world

A certain profile image of Queen Elizabeth II has been the main definitive series of stamps in Britain since June 5, 1967. It’s called the Machin head – the “most reproduced image in the history of the world,” according to Mark Copley, curator at the Royal. And I saw the original bas-relief sculpture plaster by designer, Arnold Machin. I could have googled it, of course. But here it was, 40 centimetres long by 30 wide, a ghostly image, all white; the Queen caught in time. Under glass at the Royal, it sits alongside a bas-relief sculpture by William Wyon of Queen Victoria in 1837, which was used as the design for the Penny Black. That image of Queen Victoria was used on stamps throughout her life. Even though the image of Queen Elizabeth II on British coins has been updated twice (1984 and 1998), the one on British stamps has not. I was struck by a sense of her constancy as an iconic figure. “Is the current Queen copying her great-great grandmother?” I asked. “I wouldn’t presume to know,” Walton replied.

As revolutionary as e-mail

Until Rowland Hill began postal reform in England in 1837, sending a letter was something only the rich could afford. Uniform penny postage – introduced in 1840 – triggered a number of social changes: increased literacy, education, commerce and connection.

A crafted piece of printed history

In 1940, there was talk of an alliance between France and England – a stamp was even designed to commemorate it, showing then-French president Albert Lebrun and King George VI. In the British Postal Museum & Archive, I was shown the various iterations of its designs – some with battleships in the distance, then changed to merchant ships. Approved on June 8, 1940, it was never issued. On June 17, 1940, the French capitulated to the Nazis.

Another documentation of a reality that never came to be: King Edward VIII’s coronation. For his coronation series, the King approved a design with castles in the background in March, 1936. Essays (or trials) were printed by hand. Late in the design process, “from on high came the direction that the King would like to see himself crowned,” explains Douglas Muir, curator of the British Postal Museum & Archive. A design showed the monarch’s head with a large crown. Again, trials were hand-printed. On Dec. 11, 1936, the King abdicated.

A quaint investment

Stanley Gibbons, a firm once known solely for its stamp catalogues, reinvented itself in 2004 as an investment company specializing in stamps. “These are rare, tangible assets,” says Keith Heddle, managing director of investments, adding that stamp assets have seen “very stable double-digit growth over the last decade. In our swipe-and-text, snapchat world, there’s a real desire for permanence and to look back at heritage and history.”

The most expensive stamp in the world is the British Guiana (now Guyana) one-cent magenta. Issued in 1856, only one specimen is now known to exist. It sold this year at auction in New York for $9,480,000 (U.S.).