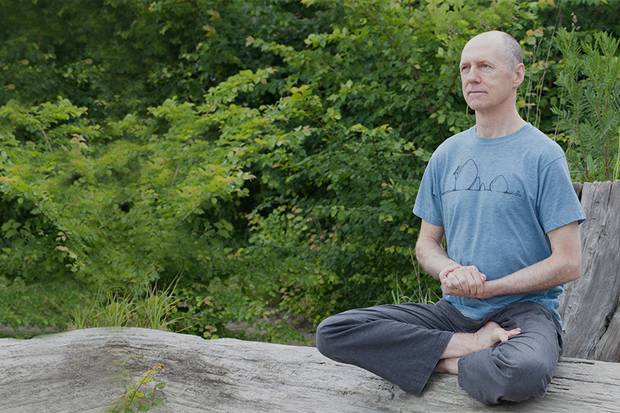

Vancouver yoga teacher Bernie Clark says yogis should stay within their limits rather than pushing their bodies into extreme positions. ‘You don’t have to put your foot behind your head,’ he says.

This is the second story in a four-part series on men's health. Other stories in the series are related to nutrition and high-intensity activities.

It was an eye-opening experience. A third-eye opener.

A lithe, grey-haired gentleman was practising on a yoga mat next to mine. He wasn't following along with the class.

Rows of us were sticking bridge poses, feet and shoulders on the ground, hips in the air. He was instead in a full wheel pose, an older man with his back arching high off the ground like a child's. I can't (and will never) muster this.

The gentleman then rocked forward and backward a few times, gaining a little momentum and then flipped himself up and forward to a perfect standing position. It was astonishing.

This particular studio in Toronto tends to attract more advanced yogis, and even cultivates a competitive edge in class, a no-no in yoga where it's supposed to be more about following at your own pace. The gentleman gave a serious look of self-satisfaction after I gave the smallest of nods, acknowledging his feat.

Yet the flip, while inspiring, put the practice of yoga into perspective. It's not about aiming to do what you can't do, it's about focusing on what you can.

The stretching and strength benefits of yoga are obvious, and there's truth in the talk of yoga fostering better balance and flexibility, as well as working joints in ways joints aren't normally worked. I even buy into the rhetoric, as modern science and ancient medicine have claimed, that yoga helps internal organs and the lymphatic system remove the toxins and general, muddy waters that build up in life. The unlikely named Half Lord of the Fishes pose works wonders, if you ask me.

Also, the meditative side and the droplets of wisdom from Eastern antiquity that you get from some of the more learned instructors add a dose of mindfulness to the day.

But yoga, at least the kind that's focused on health and well being, as opposed to how you look, is about curbing your competitive instincts. That can be hard for men (and women) in a world where we're forever equating exercise with competition and our health to everyone else's.

I asked Bernie Clark, a highly regarded teacher in Vancouver, about this competitive urge.

"Let's examine this concept you have of improving," he said, shooting down my whole notion of competition. "That's a Type A thought, a yang type of thought" (in contrast to a calmer Type B personality and passive yin thought).

But this isn't just about attitude. It gets to the core of how to approach yoga. It means that holding a pose isn't about pushing the body to its limits. It's about going into the posture only to the point of stressing the body. It's a subtle difference in approach, but a big one.

"You don't have to put your foot behind your head. You don't have to go further," Clark said. "The idea of improving could lead to a lot of injuries. The intention isn't to get to a particular place. The intention is to create a stress, and if you're already there, stop thinking about improving. You're there."

Pulled muscles, as well as joint or hip pain, are easily possible from overdoing it. A University of Sydney study published this year found that 10 per cent of practitioners suffered musculoskeletal pain of one kind or another from yoga, although this is around the same rate of injury in other fitness activities, the study said. Good teachers will typically ask students if anyone has injuries or ailments as they start class.

And teaching a safe, sane approach will remain key as the hordes of yoga acolytes continue to grow. A study by Yoga Journal and Yoga Alliance found that more than 36 million Americans, for instance, practise yoga, up from 20 million in 2012. A large part of that is an increase in men, at 10 million in 2016, up from four million in 2012.

Vancouver yoga teacher Bernie Clark got into Zen meditation in the mid-1970s to reduce stress and then moved to yoga to aid his meditation. His teaching specialty is yin yoga.

Clark, who is 63, came from a stressful career working at Xerox and then MacDonald Dettwiler and Associates (the maker of the Canadarm). He knows about Type A types. He was one. He got into Zen meditation in the mid-1970s to reduce stress and then moved to yoga to aid his meditation. His teaching specialty now is yin yoga, which can consist of only a half dozen poses or so, held for many minutes at a time, during yoga practices which last an hour or more.

It can be surprisingly gruelling. The poses are meant to drill down to the core of your muscular system and connective tissue.

A common occurrence is for a student to push himself, Clark said, "and you'll go up and ask him how he's feeling. And he'll go, 'I'm good. I'm going to feel this tomorrow.'"

It's the old habit of equating muscle soreness with a good workout.

But, "we have a completely inappropriate relationship with pain. We don't even know what it is. You have to tell students that if they feel anything sharp, burning, tingly, electrical, these are not good signals. The body is trying to warn you: Stop doing this," he said.

I couldn't help pressing the question though that improvement feels good, and naturally improving over time enables one to twist a little further or to stretch a little more deeply. Shouldn't this be seen as a good thing, something to strive for?

"There are two broad categories in yoga," he responded calmly, sagely. "There is the functional approach, and there is the aesthetic approach."

The functional approach is all about going at your own pace, being aware of your capabilities at that moment. The aesthetic approach is about mastering the pose, being driven by competition and improvement. And he acknowledges that this does exist throughout the yoga world.

Even in ancient times, gurus "would compete with each other to win the disciples of the other groups," whether it was in debating in Sanskrit, or displaying prowess in poses, or debating yoga's philosophical underpinning, he said. In yoga's more recent history, for example, there has been the popularization of harder levels of ashtanga yoga, a style that's more about creating internal body heat and therefore tends to be more athletic. (Yoga studios will also call it vinyasa, flow, or power flow – they're versions of ashtanga made more accessible for the masses.)

Unsurprisingly, there are also yoga competitions, with national and international federations pushing yoga as competitive sport. The symbol for USA Yoga looks like the basketball player in the NBA's blue and red logo suddenly deciding to do the splits vertically.

The aesthetic yoga business (and don't forget, so much of it is about business) is especially prone to Instagram-ready poses. "It's amazing that you can get some woman who has the bones for it. Her spine just has the shape to do a really deep, lovely back bend. She can choreograph [the bend] to music. She has a beautiful background in Bali, and she'll get a million followers [on social media]," Clark said.

But Clark also remembers a certain class at a yoga conference being given by one of the most well-trained, elite teachers in the yoga world. The class drew only eight people, Clark said. "Something has changed." In other words, aesthetics, competition and attracting one million Instagram followers are all fine, but realize that these are very different from the functional approach.

"If you go to a functional approach, in which you're there to become healthy, or maintain your health, then all of that aesthetic stuff is not necessary. You are just there to stress [your muscles and joints]," he said.

To use a weight room analogy, most everyone doesn't lift weights to be the next Vasily Alekseyev, the Soviet power lifter in the 1970s. "You're not there to set a world record. Some people can do that, but you're just there to stay healthy," Clark said.

Swimming is a gentle-enough exercise for those with certain injuries, such as joint pain.

Sarah Mongeau-Birkett/The Globe and Mail

Easy does it: Five more low-intensity exercises

According to Vania Hau, a personal trainer and director of the Free Form Academy in Ottawa, here are five low-intensity exercises specifically for men who are looking to ease their way into a healthy, active lifestyle.

Walking

Walk as much as you can, every day. Ten thousand steps every day is part of the required daily physical activity, but to make sure you're not going overboard you can do a simple thing like the "talk test." If you're able to carry on a conversation [while walking] you're less likely to overexert yourself.

Swimming or cycling

Both are great for cardio, and they would be good if you have certain injuries, such as joint pain.

Hiking

You don't want to do too many non-weight-bearing exercises, so hiking is perfect to get more hills and elevation into just your normal walk. That way, you're working the legs a little bit harder.

Strength training

Work with a trainer to learn how to move properly and build strength that can help improve mobility. Improved mobility is important for injury prevention.

With a report from Adam Stanley in Ottawa. His interview with Hau has been edited and condensed.