Samin Nosrat has cooked for the likes of Hillary Clinton ("I burned the beef sauce"), dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov ("He danced in appreciation after the meal") and actor Jake Gyllenhaal. These command performances apart, the 37-year-old chef has remained relatively below the radar to this point in her career. She's worked at two well-known restaurants, to be sure – the Berkeley, Calif., landmark Chez Panisse and Florence's Ristorante Zibibbo – but as part of the team, one of many cooks toiling away.

She's moving from backstage to the limelight this month, with the release of her first book, Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking. It's had prepublication nods from Bon Appétit ("a cookbook you'll actually cook from") and the U.S. National Public Radio (the "next Julia Child"). A frequent contributor to The New York Times food section, Nosrat has also just been asked to front a big-budget television show – if you don't know her or her work already, chances are you soon will.

Her book, 17 long years in the conceiving and writing, is a curious thing: part memoir of her salad (making) days at Chez Panisse, part a passionate food geek's articulation of a unified theory of cooking, part a practical, unpretentious guide to becoming a better cook. It contains excellent step-by-step guides to buttermilk panna cotta, grilled artichokes, almond cardamom cake and a labour-intensive, herby Persian frittata, but its chief aim is to liberate insecure home cooks from a slavish reliance on recipes.

Recipe: Samin Nosrat's grilled artichokes from her new cookbook

"I want you to be able to see what's fresh in the market, and to develop the confidence to make something good of it," she says in her book-filled Berkeley apartment. "Or, if you haven't shopped, to look at what you have in the fridge and to throw something together." She says old-fashioned recipes are included because "the publisher insisted" – more than a how-to guide, she wanted to give home cooks transferrable "tools."

As a girl, Nosrat didn't look headed toward a culinary career. The U.S.-born daughter of Iranians who left just before the 1979 Islamic Revolution, she grew up in San Diego. "I was the overachieving kid of immigrants. I decided I was going to be both a lawyer and a doctor," she says. Then, a high-school English teacher turned the would-be double professional on to reading and writing and, on his recommendation, she went to study literature at the University of California, Berkeley. "Then, I was going to be a poet – that was my big money-making scheme."

Ironically, it was another aspiring poet who inadvertently diverted her from this path, a "rosy-cheeked, sparkly eyed" fellow undergrad who mentioned his desire to eat at Chez Panisse, the NorCal restaurant, founded in 1971, that is credited with leading the California Cuisine movement – in a nutshell, organic and foraged ingredients combined artfully.

"Restaurants weren't this thing in San Diego, with its fish-taco shops and pizzerias," Nosrat says. "Still, I liked fancy things, bouge things, and if everyone else was going there, I wanted to try it."

The pair saved for four months, carting their coins to the bank the night before, getting out two crisp $100 (U.S.) bills and two $20s, and the meal did not disappoint. "Dessert was chocolate soufflé. When the server brought it to me, she showed me how to poke a hole in the top … then pour in the accompanying raspberry sauce. She watched me take my first bite, and I ecstatically told her it tasted like a warm, chocolate cloud."

Afterward, Nosrat wrote a note of appreciation to Chez Panisse founder Alice Waters and took it to the restaurant, with her resumé, to ask for a job. "The woman who'd watched me enjoy the soufflé was the woman I met with. She read the letter – the résumé had nothing relevant – and gave me a job on the spot."

Nosrat fell in love at first sight, as she writes: "The sheer beauty of the kitchen, filled with baskets of ripe figs and lined with gleaming copper walls, mesmerized me." Twenty years old when she started there, she moved gradually from early-morning lettuce-cleaning and pasta-prep up through the ranks, learning lessons she tries to distill for her readers.

The kitchen she describes is not the one from many other chef memoirs, a space with cursing, drug-addicted pirates swaggering around. "It was started by a woman, and for every thing, there was a method, a way of putting the tie on the garbage bags, of putting the garbage in the can," she says. "There was no yelling, no screaming, everyone moved with grace and efficiency."

Then she raises her eyebrows, waggles her head and bursts out laughing. "There was aggression, of course, but it was deeply passive aggression."

The other restaurant where she trained, Zibibbo, was also run by a woman, the legendary Benedetta Vitali. "She's somehow thrived in what is a macho scene. There was certainly this politics to her being … the boss."

Nosrat has also faced – or decided to face – political challenges of her own. A U.S. citizen by birth, in late January she joined a large, impromptu protest at San Francisco airport after the Trump administration tried to limit citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries entering the United States and was interviewed by The Associated Press; her words published around the world.

"I am the child of refugees," she said. "If they were not allowed to come here, I do not know what my life would look like." In the interview, she adds, "I have always been searched at the border. In a way, what's happening now makes that discrimination more evident."

The recipes in her book feature some of the Iranian recipes her mother cooked when she was young, as well as working the two other culinary veins she knows best, Italian and Californian cuisine. Her still-extant love of literature outs itself in sly references to Wallace Stevens and a slipped-in quote from Seamus Heaney in which the Irish poet calls butter "coagulated sunlight."

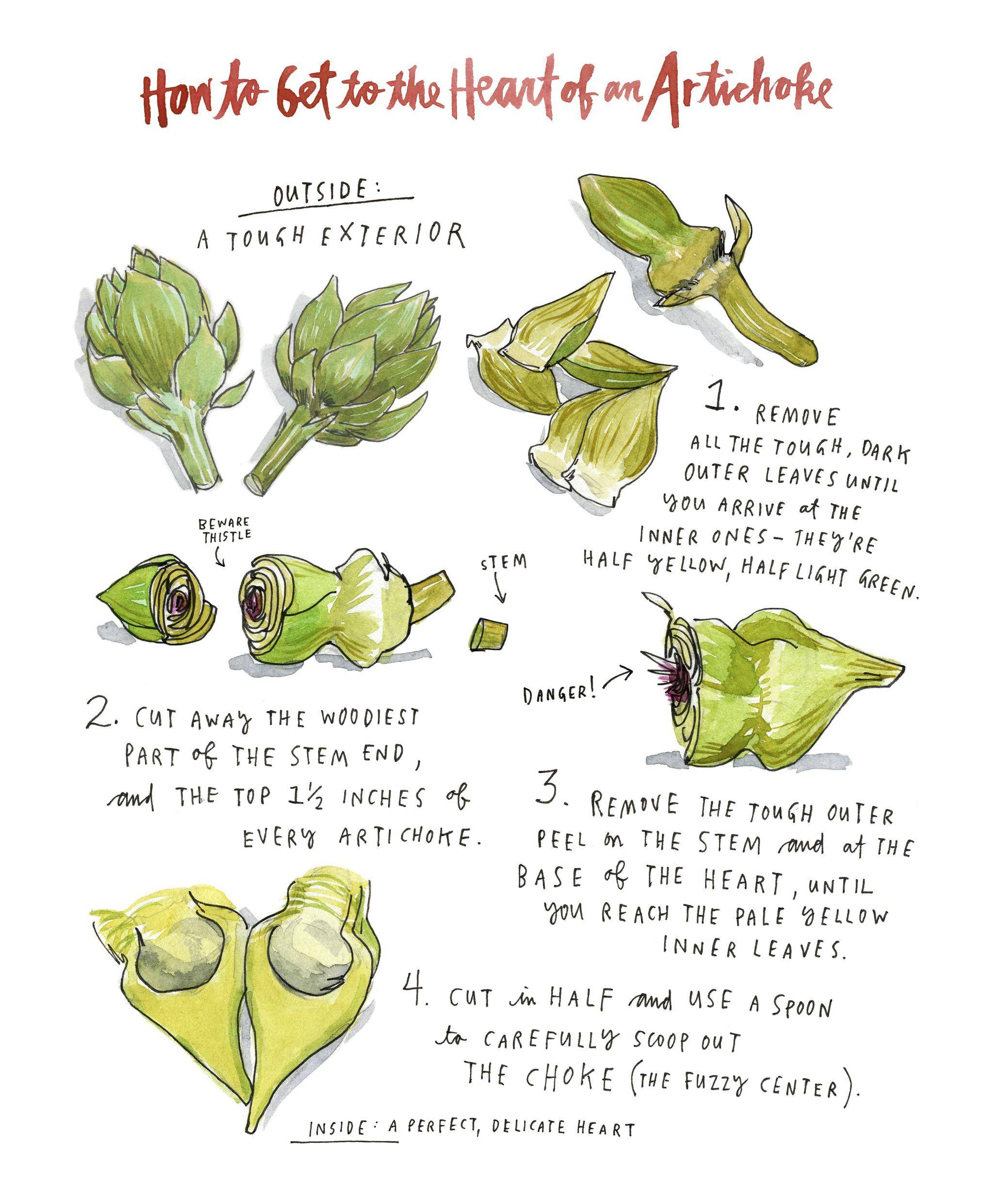

San Francisco-based illustrator Wendy MacNaughton provides pictures that communicate what even many well-chosen words fail to get across – how, for instance, to dice an onion efficiently. As important, the illos add notes of play to the rigour on evidence throughout: Next to the bottles of vinegar and lemon juice, she's drawn in the acid section is a little, unobtrusive vial labelled LSD.

Although the Berkeley chef's book is very free-to-be-you-and-me in its approach, there are certain liberties even she can't countenance. "Throw out your iodized salt," she writes. "It was developed in a time where people didn't get much iodine from the rest of their diets, but they do now. It tastes metallic. Toss it! Grate parmesan fresh. Use good olive oil."

This is one of many Chez Panisse lessons: Once, when Waters asked her chefs to take part in a tomato-sauce-making contest, she could taste that many had used the rancid olive oil they had at home in making their sauces. "The consciousness around olive oil wasn't there then, even among our cooks," Nosrat says.

Now, she's passing such simple, but essential, teachings on.

Nosrat is a practised instructor – she taught Michael Pollan, one of the world's leading food writers, how to cook – and her book expertly reduces the art and craft to a mastery of the four elements named in the title. "Salt, fat, acid and heat are the four cardinal directions of cooking," she writes, "and this book shows how to use them to find your way in any kitchen." (The food-and-travel-oriented television show will feature one of the titular subjects per hour-long episode.)

In general, Nosrat is an advocate for tasting and adjusting, tasting and adjusting, a method she teaches in classes by slowly combining the elements of a Caesar salad, and, after learning and tasting what the different elements add, getting students to call out what they think it needs. "Of course, at the end of those classes, although we've learned how to do it in this intuitive way, they all want the recipe, something to hold on to.

"At first, I would say you don't need the recipe, you've learned how to combine the elements, but then I gave up. In the kitchen, in life, people, sometimes they just want the recipe."