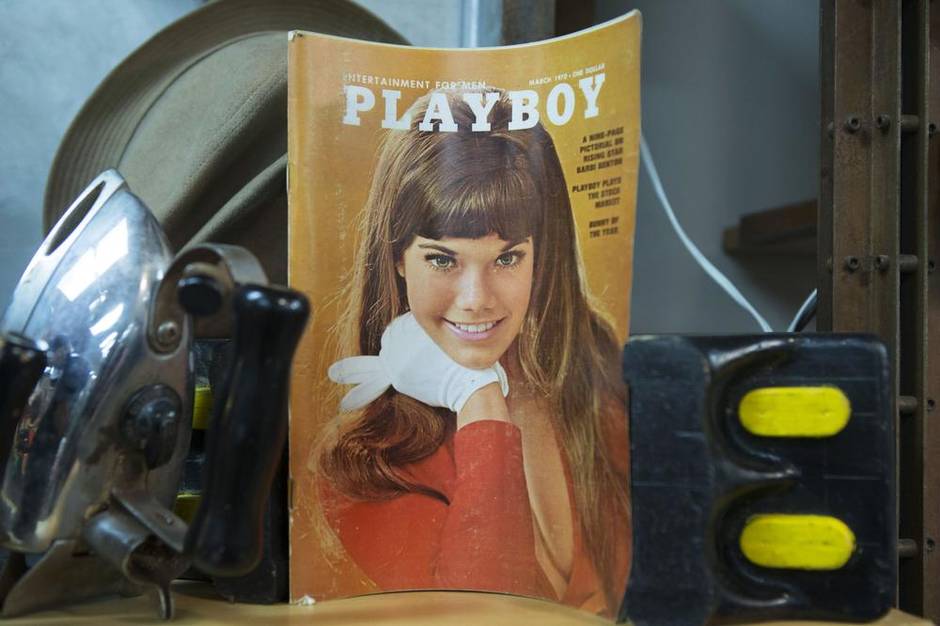

I blush when the wrapping paper comes off the April, 1973, issue of Playboy. There’s no nudity on the cover of my 40th-birthday gift – just the nose, chin and glossy red lips of Swedish model Lena Soderberg, who has a postage stamp on the tip of her tongue.

My heterosexual male mind is flummoxed. I might have expected a gift of throwback pornography from a male friend, but not from a woman who isn’t my wife. I know my friend Amanda Smith has a deep love of all things vintage, which extends from her living room to the optical store she owns in Peterborough, Ont., and that she enjoys a cheeky laugh. But I’m also aware that many women find Playboy’s erotic photos an objectifying affront to feminism. So I’m not sure why my modern, liberated, platonic pal is giving me one.

Then I learn that women are enthusiastic purchasers of vintage Playboys – and that the challenges of feminism aren’t so clearly defined.

My “birthday issue” isn’t among the dozens of men’s magazines from the 1960s, 70s and 80s artfully arrayed around the west-end Toronto vintage emporium Mrs. Huizenga. “I get lots of them, but I have a hard time keeping them in stock,” says owner Catherine Huizenga, who sells the periodicals for between $5 and $10. “Women often buy them as birthday gifts or aphrodisiacs, but mostly they buy them for themselves.”

Across the country, vintage, antique and used-book dealers say back issues of Playboy are flying off the shelves. The magazine came to life in December, 1953, and pre-1980s issues are hilarious retro romps. The mid-century-modern aesthetic they showcase is all the rage – “These magazines are showing up on a lot of coffee tables,” Huizenga says. The pictorials, interviews, cartoons and kitschy advertisements are being embraced by interior and fashion designers, and celebrated in museum exhibits and on the female-dominated Pinterest digital bulletin board.

This is one trend I can embrace: More Playboys could be coming my way as gifts (from anyone); I like the idea of my wife giving me one (for any reason); and I like the idea of women giving them to one another. But it still doesn’t add up. If the goal of feminism is to achieve equality between the sexes, then shouldn’t modern, liberated women oppose the dissemination of “Entertainment for Men” from any era?

The appeal of vintage Playboys is all about context, says Jennifer DePoe, director of Toronto’s annual Feminist Porn Awards and manager of the city’s Good For Her sex shop.

“In the sixties and seventies it was taboo to be empowered by your sexuality. Your role was to be an object for men,” she says. “These Playboy models went out and said, ‘I own my sexuality, I’m going to put myself in this magazine and I’m going to get paid for it.’ This was pretty feminist for the times.”

DePoe agrees that the trend is also fuelled by a widespread backlash against modern depictions of women.

“Back then, people weren’t expected to have this very specific body type that’s impossible to achieve. Looking at old Playboys nowadays, it feels like you could almost be that person.” DePoe calls old Playboys the “comfort food of porn,” and adds that the ubiquitous pornography of today “doesn’t appeal to a lot of people when it’s unrealistic or degrading.”

By now I’m getting mental whiplash from all the backlash, and it gets worse after speaking with Anne Eaton, an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Illinois-Chicago who specializes in feminist critiques of pornography.

After I outline the vintage trend, she immediately references Ariel Levy’s 2004 book Female Chauvinist Pigs, which explores the rise of “raunch culture,” the objectification of women by other women (think Girls Gone Wild videos and pole-dancing classes).

“Pornography is pitched to women as a way of affirming their sexuality, and in a sense, of being feminist,” says Eaton. Again, I can’t figure out the catch.

Playboy’s objectification of women and disregard for female gratification are both troubling, Eaton says, but the most alarming gender imbalance involves the allocation of resources.

“These magazines are part of a mechanism that makes women hypervigilant about their sexiness, and makes them put all this time, effort and money into being sexy.

Men, meanwhile, can focus on their careers and other important aspects of their lives.”

The rise of vintage Playboys, Eaton says, extends the reach of raunch culture to a cultured, “hipsterish” demographic that embraces the vintage images with an ironic, playful wink. Feminist critics, the professor says, face the classic accusation of being “deeply unlikeable, unattractive, humourless bitches” who can’t take a joke.

Now I’m even more confused, and conflicted, over the vintage trend. I’m all for gender equality, but does female attractiveness have to suffer in order to achieve it?

Is my birthday Playboy part of a mechanism that determines what female attractiveness should look like? Is this the same mechanism behind $250 bikinis, Brazilian waxing and the litany of other female predilections I find utterly incomprehensible?

While shopping in Mrs. Huizenga, the friend who gave me the magazine sets me straight. “Women like looking at old Playboys because there are real bodies inside,” Amanda says, as if to a small child. “Men like looking because those bodies belong to naked women. It’s natural.”

I can’t argue with that. But in fairness, I should probably run out to buy a $250 Speedo and a gallon of hot wax.