There are myriad reasons to recommend travel. One of the more splendid things is its efficacy as a filter. If you are on the beach in Cancun and strike up a conversation with a passerby, you'll pass some time; perhaps the experience will be interesting or stimulating, though more likely it will be shallow, or dull. But if you are, say, chopping your way with a machete up an overgrown jungle stream in search of the lost Temple of the Jaguar God, and you meet another soul who has the same motivation, you can guarantee an interesting conversation around the campfire. Travel sifts away the dross and connects you with people who realize they are alive on our wondrous earth and are game to seize each day. This filter serves you well on every splendid adventure, but clogs when you stick to the well-worn tourist paths.

That's why set plans often do a traveller a disservice, as no travel plan survives contact with friendly forces. I've said on more than one occasion that good people greatly outnumber nasty people worldwide. There is a network that existed long before social media: the network of persons of good will, who will introduce and pass you to other persons of good will, such that you can take a friendly look around a town, a nation, or the world, as you like. There is no similar network among nasty people. They are on their own, and if you know what is good for you, you will leave them alone.

Lately I've been spending more time in Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine, making new friends and staying in touch with the old friends, travelling at a slower pace to allow more time for writing and thinking. Mostly, going somewhere new has been replaced, necessarily, by return visits, and that brings its own rewards, to see what has changed and what remains. Life is endlessly fascinating.

The traveller who loves travel for its own sake is found, at the end of the journey, in possession of a treasure that cannot be picked apart or taxed, or fought over after death. A person who put as much energy into building a mansion would find the taxman assessing it, and having to pay property tax accordingly. There would be jealous neighbours to endure, and it would have to be sold eventually to pay the owner's death taxes. If that mansion, even built by owner's own hands, was assessed by the government at millions of dollars, then people would curse that person as part of a "1-per-cent elite," hoarding the resources that ought to be distributed among the needy. And yet, a traveller like me has accumulated experiences worth millions of dollars; actually, many of my experiences are, or will soon become, priceless. They will be impossible to duplicate as nature and our surviving relics of antiquity disintegrate or are sequestered for the lucky few.

And no taxman can come away with so much as a smidgeon of my rich experiences, any more than it is possible to get blood from a stone. This alone makes experiences garnered through travel a superlative store of value in a time of strident talk of income inequality. But my wealth can be shared – not with the taxman, but with anyone who asks for a story. And its value does not diminish in the telling. In a sense, the traveller can have it all and give it all back to the community, as long as the travels were adventures and fun or interesting for the listener, and not mere box-ticking or country-counting in the service of tedious one-upmanship.

Roald Amundsen, the early-twentieth-century Norwegian polar explorer, once quipped, "What is the point of going somewhere someone else has already been?" He invented the concept of independent adventure travel in its modern form. Indeed, he was ahead of his time in many ways, and more like a modern adventurer than I am, a blogger and crowdfunder who concocted the idea of working the media to raise funds, and attracting an admiring audience of vicarious armchair travellers. But we are in a post-Amundsen world now. Humans have become numerous, and it is in our species' nature to spawn adventurers, so it's a tall order to find feats of derring-do yet undone, and many of those remaining seem contrived. Consider the man who set out to walk the Amazon, a first. It took him years of squelching through mosquito-infested muck instead of a swift and sensible float of a couple weeks. What will he do for an encore? Canoe the Sahara?

Some people say it's a small world now. And certain adventurers have a visceral need to feel caught up in events on a scale far bigger than themselves, a need that cannot be satisfied in such a small world, or with good works done for their own sake. So what is the point of travelling to places where someone else has already been? I hope that I've helped to answer that question. Because otherwise we are left with good works that do not scale, and the threat behind the anonymous quote "In a society that has destroyed all adventure, the only adventure left is to destroy that society."

Villagers and tribal people often have a tremendous sense of fun and can get a laugh at the absurd, including the unfathomable ways of nomadic backpackers. They were happy to tell me why they make a home where they do and behave as they did, what they do for a living, how they raise children, what they expect from life. Their answers have given me much to reflect on. Importantly, comfort is not all it's cracked up to be, and can be dispensed with. Naturally, I was at times lonely, bored, and frustrated. But most of the time, I'm happy to say, I accepted, with as good grace as I could muster, any obstacles and ill-luck.

My understanding of the world comes not only from common sense, but from gleaning the uncommon sense that comes from chatting with a rogue's gallery of bandits, tour guides, tribesmen, subsistence farmers, students, terrorists, ministers, businessmen, police, and exhausted NGO workers at their local watering holes. These moments can be had in the most out-of-the-way and unlikely places. The single greatest revelation from my two decades of more-or-less constant travel is something that probably should have been obvious before I started: the world is not small. The people who share our planet are diverse, and there is no simple answer to the meaning of life.

Yet hidden behind some very peculiar customs and cultural differences, people are basically good and are worth knowing whatever the race or culture they hail from, and in this way we are all remarkably similar. If you are accepting of their circumstances, rather than being judgmental and rigid, you will have no problems getting along with people anywhere on the planet. To avoid the trap of the soft racism of low expectations, I am always mindful when making comparisons between different races and cultures to compare hillbillies in Malaysia to hillbillies in the Appalachians, rednecks to rednecks, scholars to scholars. When I do this, the commonality of our human experience jumps out at me. However, anyone who insists on comparing a Mongolian redneck to a Melbourne white-collar worker, and is bullheaded with their opinions, arrogant and condescending, will have to get used to suffering a narrow mind and wearing an appalling frown. The world is not a simple place of firm identities suitable for constructing some ideology. We all have opinions, of course, and most people can be diplomatic if they try hard enough, but I think that effort is better directed, instead, at understanding where people are coming from.

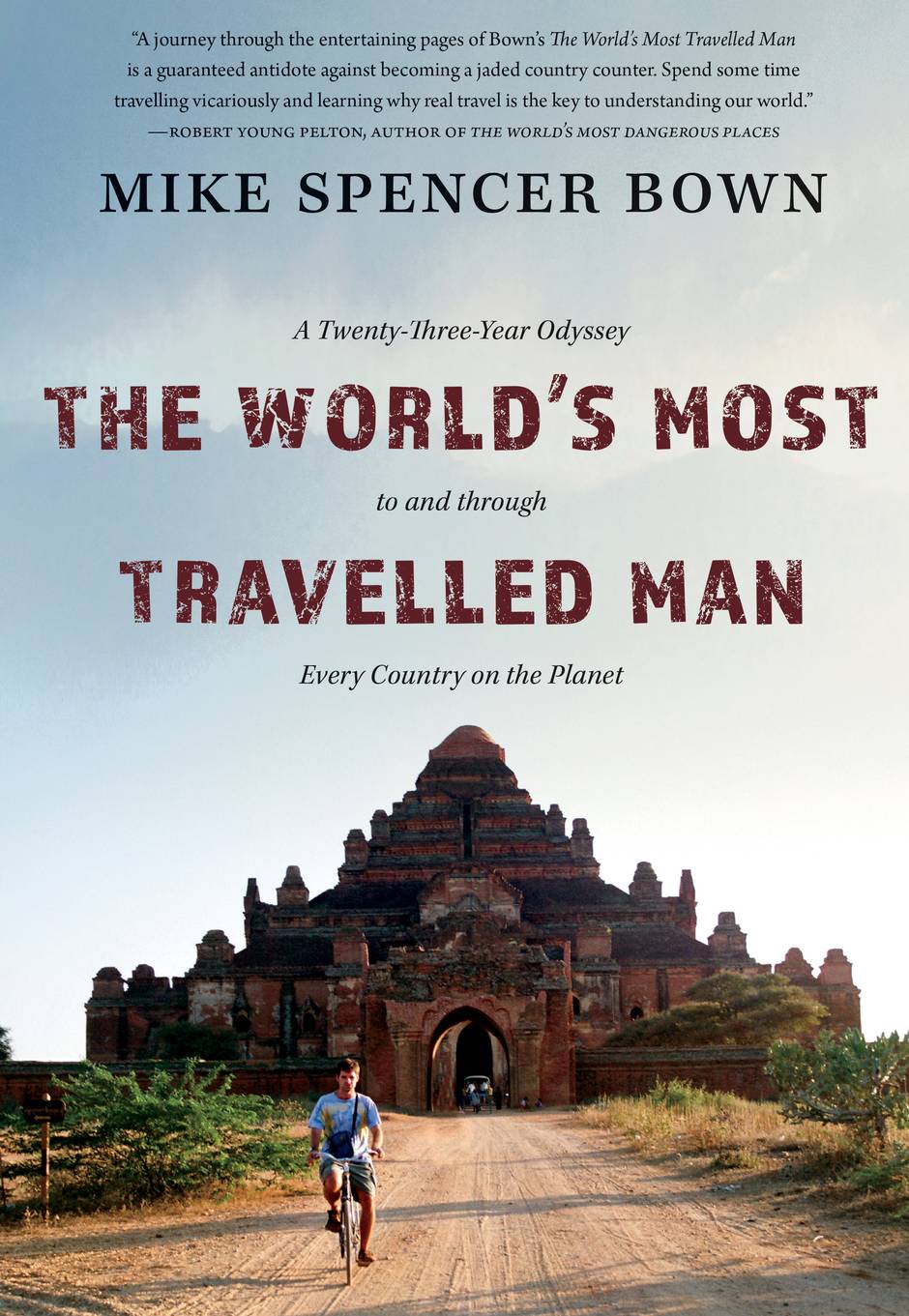

As compensation for my outlandish roving, I've amassed a body of knowledge and a collection of adventure stories of a breadth to satisfy my own curiosity. Because I had put my whole adult life into it, reporters called me the world's most travelled man, and I suppose, according to the backpacking, freestyle travel so dear to my heart, I am - having followed my dreams to explore our planet free from gimmickry, not to prove a point, but to let the adventure teach me what it means to be alive in what is a chaotic, alluring, and tremendously large world.

From the book The World's Most Travelled Man: A Twenty-Three-Year Odyssey to and through Every Country on the Planet, by Mike Spencer Bown, © 2017. Published by Douglas & McIntyre. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.