There is nothing particularly eye-catching about this flat, brush-covered island about a dozen kilometres upstream from Fredericton along the Saint John River.

It is, however, unique – and for that reason it has been declared a reserve by the Nature Trust of New Brunswick.

Nature cannot break Burpee Bar. Ice scours it like steel wool as winter water levels rise and fall and the ice pack grinds its way downstream. Spring floods drown the bar. And yet, each summer, rare plants such as Brunet's milk vetch and Rand's goldenrod spring up defiantly.

Burpee Bar was once renowned for the Atlantic salmon that could be found in the surrounding pools – the iconic sport fish were large and healthy and numbered in the thousands.

But no more. Burpee Bar might be able to handle nature, but its waters cannot survive man.

What pollution doesn't kill and the dams don't block is devastated by overfishing: Today, this stretch of the Saint John River is closed to fishing.

"We're basically down to counting individual fish," says Simon Mitchell, the area adviser on World Wildlife Fund Canada's Living Rivers Initiative. "The Saint John River historically was the salmon river. It wasn't the Miramichi. It wasn't the Restigouche. It was the Saint John River."

Philip Lee would agree. Mr. Lee, a journalism professor at St. Thomas University in Fredericton, is a passionate fisherman on the river – in those areas where fishing is still permitted. He is the author of Home Pool: The Fight to Save the Atlantic Salmon.

"This may have been the largest producer of migratory fish in eastern North America," he says as he poles his canoe through the currents swirling past Burpee Bar. "They are here in the hundreds now instead of the hundreds of thousands."

The numbers are verified by the Atlantic Salmon Federation, which released a report last August that tallied 482 grilse (young salmon returning to the river to spawn for the first time) and 173 large salmon along the Saint John River. The year before it counted 586 grilse and 86 large fish – a far cry from the mid-1990s, when the average count was more than 3,000 grilse and almost 2,000 large salmon.

"The St. John certainly needs all the help it can get," the report concluded.

A mist rises amid several old bridge pilings along the Saint John River in Fredericton in 2015.

Jeff McIntosh/The Canadian Press

Is it the St. John River or the Saint John River? Both, apparently. The New Brunswick Ministry of Tourism, Heritage and Culture, which is responsible for toponymy – official place names – says the waterway, in both official languages, is the Saint John River and Rivière Saint-Jean. But many historians beg to differ, pointing out that the river – called the Wolastoq ("beautiful river") by the Maliseet – was renamed by Sieur de Monts and Samuel de Champlain in 1604 after they reached the river mouth on the Bay of Fundy on June 24, the feast day of John the Baptist. Hence, St. John.

No matter what it is called, it is most assuredly "beautiful." The Saint John River runs for 673 kilometres as it drains a vast, ancient mountain area that lies roughly two-thirds in New Brunswick but also includes sprawling hills in the northeastern United States and an area in the southeastern portion of Quebec.

It is a river of vastly different personalities, raging like the Niagara as it roars through Grand Falls, placid enough to be called "The Rhine of North America" as it slides through the rich farmland of the Saint John River Valley, pastoral as it passes Florenceville-Bristol ("The French Fry Capital of the World") and slips under "The World's Longest Covered Bridge" at Hartland, and park-like as it moves through the city of Fredericton and twists its way past the Oromocto First Nation, touching vast Grand Lake and moving ever southward toward Saint John.

It has falls and rapids and dams. It provides a border between the United States and Canada. And it is a major tourist attraction at Saint John, where the high tides of the Bay of Fundy and the ceaseless flow of the river create a phenomenon known as the Reversing Falls.

"Happiness is the word which always comes to my mind when I think of the River St. John," novelist Hugh MacLennan wrote in his 1961 book Seven Rivers of Canada. "It is the shortest of our principal streams, being only about 420 miles long, and its system is a small one. Yet it offers so much variety of scenery that a stranger travelling along it encounters a surprise every twenty miles or so. The St. John is intimate and very beautiful."

It is also a river of long history. First Nations have lived along its course for 10,000 years. The river was a critical transportation route in New France. When France and Great Britain fought during the Seven Years' War, 1,500 British soldiers headed up the river in early 1759, destroying Acadian settlements along the way. In one campaign known as the "Ste Anne's Massacre," New England rangers pillaged and burned the village of Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas. When the captured leader of the Acadian militia refused to swear an oath of allegiance to the Crown, the soldiers killed his family members in front of him, and still he would not swear.

Perhaps it was this tale that inspired Fredericton poet Alden Nowlan to describe the waters of the river he so loved as "the colour of a bayonet."

The Harbour Bridge in Saint John spans across a segment of the historic New Brunswick river.

Robert McGouey/Alamy Stock Photo

Upstream around the mill town of Edmunston, Acadian flags are common today, immediate reminders of the Great Expulsion that took place between 1755 and 1764. Of the roughly 14,000 Acadians in the larger region, 11,500 were deported because the British considered them disloyal.

Many Acadians ended up in Louisiana, some later returning to start life again in the Upper Saint John River Valley. There is even a quirky portion of the province known as "The Republic of Madawaska" that has its own flag and "president" – really the mayor of Edmunston.

A generation after the Expulsion of the Acadians, it was Loyalists fleeing the American Revolutionary War. They came by the hundreds to settle in the growing centres of Saint John and Fredericton and to build charming small communities such as Woodstock.

To commemorate the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812 and celebrate the long and storied history of the river, Eric and Kim McCumber paddled the length of the Saint John in 2013, often wearing period costumes and accompanied by other paddlers. Mr. McCumber's grandfather and great-grandfather were captains in the steamboat era of the river, and while so much of the valley has been settled and farmed, he was delighted to discover how much still appeared as his ancestors would have seen it.

"It's not a wilderness paddle," he says. "But in places it can feel like it."

Mr. McCumber – a retired chemical engineer and amateur historian who has written a book about the river's first European settlement – sees the Saint John as a great "communications" system. Historians have called it "The Road to Canada" with cause.

It was the river that allowed military travel and settlement. Before the railways, paddle wheelers delivered supplies. The river was at the heart of the massive timber industry, carrying logs downstream from the high hills to sawmills in Fredericton and Saint John. American author Annie Proulx's most recent bestseller, Barkskins, is about the early timber trade and is largely set in New Brunswick.

During the U.S. Prohibition years, the upper reaches of the river that formed the boundary between New Brunswick and Maine were popular with bootleggers. The ferry between St. Leonard on the Canadian side and Van Buren on the other was said to regularly feature American travellers crossing the river only to quickly return on the next ferry with "bottles of Dominion rye in hip pockets."

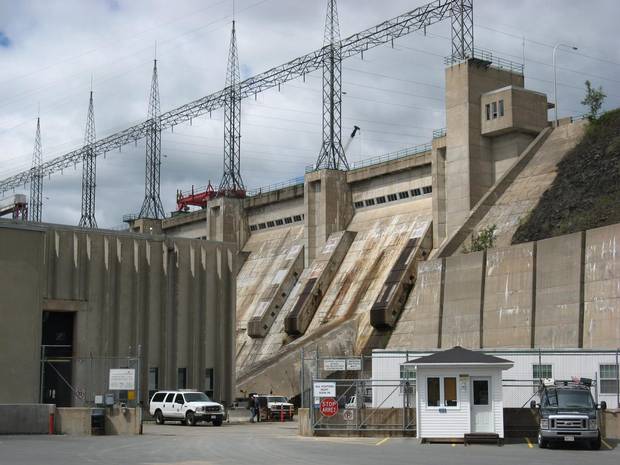

The Mactaquac Dam near Fredericton was added in 1965, and dramatically changed the flow of the Saint John River, cutting salmon off from their spawning grounds.

Brian Atkinson/The Globe and Mail

Today, the Saint John River is a vital source of hydroelectricity. The Grand Falls/Grant Sault dam was built in 1925 over a deep, dramatic cataract where, legend has it, a Maliseet maiden named Malabeam, who had been captured by the Mohawks, sacrificed her life by leading a Mohawk war party over the falls, thereby saving her village.

The falls remain a major attraction – even though at the height of tourist season, the river virtually dries up as the water is diverted for energy production.

Not so this year, though, as evening rains and fine daylight weather have created a banner year for Zip Zag, a local zip-line operation that charges $40 to fly across the spectacular gorge and back.

"It's the setting," says Christine Ouellette, who co-owns the company with her husband, Eric. "Other places have trees, but we have the falls and the gorge."

Larger hydroelectric dams were added at Beechwood and Mactaquac in 1955 and 1965, respectively. The damming dramatically changed the flow of the river, creating huge reservoirs but also cutting off salmon from their spawning grounds. The diminishing salmon fry were often killed as they fell into the turbines while trying to make their way out to sea.

But before any of this European settlement or development, the Saint John River was the Wolastoq and it was home to the Maliseet, or Wolastoqiyik, who lived along its banks, hunting through the forested hills and fishing the bountiful fish that fed and spawned in its pools.

In 2011, three specific Maliseet locations along the river were designated a National Historic Site. Two years later, the river became part of the Canadian Heritage Rivers System.

To the Maliseet, the river was Creation itself. In the oral tradition of the people – as described by elder Gabe Paul of Pilick in 1917 – a monster once stood between the Wolastoqiyik and their advancement up the waterway. When the monster was killed, it fell as a tree, and "this tree became the main river … and the branches became the tributaries, while the leaves became the ponds at the heads of these streams."

The First Nations who lived along the Saint John River and the salmon in the river cannot be separated, WWF-Canada's Mitchell says. "They are entwined," he says, "and have been since time immemorial."

A motor boat sits tied up to a dock along the Saint John River in New Brunswick.

iStock

"I've been building canoes since high school," Steven Jones says.

Now 60, he carries on the trade of his father, Carl, who was one of the key builders for the world-famous Chestnut Canoe Company, the Fredericton firm whose cedar-and-canvas products were prized by such iconic Canadian paddlers as Bill Mason, Pierre Trudeau, Tom Thomson and Grey Owl.

The canoes, first built by William and Harry Chestnut in 1905, became so famous that most manufacturers in North America emulated their designs, particularly for the popular Prospector models. As Greg Clark, the popular outdoors writer for the Toronto Star, said in a letter to the Chestnuts in the early 1950s, "Your canoe is like a pair of good-fitting shoes."

The history of the canoes – lovingly told in Roger MacGregor's 1999 book When the Chestnut was in Flower – came to an end in 1979. With plastics and other new materials taking over the recreational canoe market, the Chestnut factory simply closed down.

Years passed and the Oromocto First Nation, downstream from Fredericton, decided the canoes could be built there. After all, many of the best canoe builders for Chestnut had come from the Maliseet community.

Steven Jones worked for Chestnut to the bitter end. When the Oromocto First Nation took possession of the original moulds, he was soon back at work building the same canoes he began building as a teenager.

"These moulds are over 100 years old," Jones says, waving his hammer toward the back of the Great Spirit Canoes factory. "And we're still banging canoes off them."

The canoes built by Great Spirit are exact replicas of the originals, but they cannot carry the Chestnut name because it was purchased decades ago by an Ontario canoe builder.

"These are real Chestnuts," Jones contends defiantly.

Some aficionados of the original Chestnuts treat their vessels like works of art, but Jones has no time for such thinking. "These canoes are built to be used," he says. And used, whenever possible, on the Saint John River that flows within sight of the Great Spirit factory.

"I've fished it," he says. "I've canoed it. I've had motor boats on it. All my life. It's a beautiful river, and these canoes were made for it.

"The Saint John is a nice river."

The Reversing Falls and a pulp mill are seen in Saint John during low tide in the Bay of Fundy in July 2009.

Gaertner/Alamy Stock Photo

There are issues big and small along the path of the Saint John River, but even the small ones are huge to those affected directly.

The people of little Gagetown, for example, have lost their ferry, which was pretty much the main tourist draw in the area. Three ferries have been decommissioned by the provincial government, and no community is as upset as Gagetown. Farmers say they now have to travel much farther with produce. Shoppers say their trips to the larger centres are longer.

Kylia Mazariejos's complaint is far simpler: She simply wants to take her one-year-old daughter Marleigh on it.

"I wanted my kids to experience it," says the waitress from the Old Boot Pub by the river. "It was the most wonderful thing to go on as a kid. The whole town wants it back."

The sitting provincial member, a Tory, says the government should sell the ferry to the village for $1. The Minister of Transportation says "the decision is final – the ferry is not coming back." So enraged are the townsfolk over this cavalier attitude that the ferry is expected to be the top local issue in an election that is still two years away.

A far greater issue – one that directly affects the Saint John River Valley – is Energy East, TransCanada Corp.'s proposed project that would convert approximately 3,000 kilometres of natural gas pipeline to one carrying crude oil and still require 1,600 kilometres of new pipeline, most of it right down the valley.

In New Brunswick, there are two clear sides on the matter.

The Irving Pulp and Paper Mill, seen in Saint John, is one of many that run along the province’s major river.

Brian Atkinson/The Globe and Mail

One side, closer to the sea, sees the creation of 4,000 full-time jobs in the economically challenged province. Some $15.7-billion will be spent over nine years to build the line, which would bring 1.1 million barrels of crude each day from Alberta to Saint John refineries and a new export terminal. The Conference Board of Canada says the project would pump $36-billion into the national economy over the next two decades, much of the money ending up in New Brunswick pockets.

There is, however, another side. "An oil spill anywhere in this valley would be catastrophic," says Mr. Lee of St. Thomas University. "It's a river, after all."

With the National Energy Board still to rule on the controversial project, the Conservation Council of New Brunswick has produced a report sharply critical of the plan. "We believe the risk to the environment and existing jobs in fisheries, tourism, agriculture and forestry outweighs the potential benefits," the report concludes. Instead, the council argues, the province should concentrate on renewable power projects.

One renewable power source, however, is itself a major issue in the river valley: the Mactaquac dam, about 20 kilometres upstream from Fredericton. Built in the late 1960s and expected to last a century, problems with the concrete have forced a shortened timeline for the huge project; the facility is now predicted to reach the end of its lifespan by 2030.

The dam, which supplies about 20 per cent of the province's power, has been the subject of much debate over the past year.

NB Power, which owns the dam, invited the public to help decide its future. Four options were proposed: rebuild the dam and generating station, rebuild just the dam to maintain the headpond at current levels, partially rebuild the facility to extend its lifespan – or rip the dam out and let the river return to its natural flow through the area.

On Dec. 20 it was announced that the dam would be kept functioning until 2068 at an estimated cost of $2.9-billion to $3.6-billion. NB Power said this was the lowest-cost option, and while the Friends of Mactaquac Lake said they were very pleased with the decision, the six Maliseet communities that had called for its dismantling said they were "deeply disappointed," as was WWF-Canada.

Factors under consideration if removal had been the choice include flood control – Fredericton has a long history of dealing with spring freshet volumes, most recently with severe flowing in 2008 – but also salmon benefits, cottager concerns and what would replace the lost power capacity.

"It's not a free-flowing river any more, and that causes me concern," Lee says. "I do feel it needs to be released and not held back. It may or may not happen. It's a bit of a heartbreak that way."

Mr. Mitchell of WWF-Canada says that Energy East, if completed, would have about 200 stream crossings as it makes its way through the valley to Saint John. There are a great many who would prefer to avoid the risk of a spill and, instead, find future energy in solar and wind projects and, most promising, Bay of Fundy tidal shifts.

But, Mr. Mitchell says, the reality is that such solutions are neither instant nor certain. "This has always been a working river," he says, "and will continue to be so. So striking a balance is important."

The Mactaquac Hydro Electric Dam is shown near Fredericton on July 27, 2010.

Kevin Bissett/The Canadian Press

Five years ago, the Canadian Rivers Institute published a state-of-the-environment report on the Saint John River. It estimated the population of the river basin was close to half a million. Forestry, the dams, hog and poultry farms, the country's third-largest potato crop, mills, paper products, rayon, etc. have punished the river for two centuries. But, said the report, "the overall quality of the river has improved in the last 40 years."

This improvement, of course, is relative and mostly due to communities now treating their waste water. Agriculture sediments and, in some areas, untreated sewage remain major concerns.

In March, WWF-Canada released its watershed report on the river and evaluated the threats. Overuse of water was "low," habit loss "moderate" – but pollution was deemed a "very high" threat.

Mr. McCumber, the paddler, worked in the pulp and paper industry all over Canada, including the Saint John River Valley. He does not mince words when he says "the pulp mills killed the river. For generations you couldn't go near the river. People stayed away."

But no longer. On a warm summer day, there are swimmers and kayakers, canoeists and motor boats all along the river. In those areas where it is allowed, they fish for striped bass and sturgeon and, yes, the Atlantic salmon that once made this the salmon river.

"It's not perfect," Mr. McCumber says. "But it's relatively healthy."

Poling his long canoe past Burpee Bar, Mr. Lee has to agree: "It's such a beautiful river. And to have something like this so close to the city – two hours upriver and you're into a completely different world."

"We're considered 'have-not,'" adds Mr. McCumber, "but we have a wonderful place here."