“Do you know what we call him here?” says the woman sitting next to me on my first night in town. “The prick with a stick.”

“I once tried to read Ulysses, and couldn’t,” adds her dinner companion. “So I got it on audiobook. But it was still nonsense.”

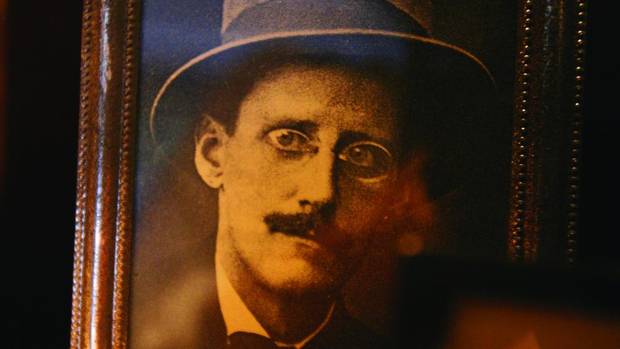

Welcome to Dublin, a city made famous, in part, by James Joyce and his book about the city’s residents, Dubliners, which was published 100 years ago this week. During his long struggle to see the book to market, Joyce famously boasted that he had captured Dublin’s very essence: “I have written it for the most part in a style of scrupulous meanness and with the conviction that he is a very bold man who dares to alter in the presentment, still more to deform, whatever he has seen and heard.”

But, as the book reaches its centenary, and as Joyceans around the world get ready to celebrate another Bloomsday on June 16 (the day on whichUlysses is set), a strange thing seems to be happening in the legend’s hometown. Joyce remains an essential tourist engine for Ireland, drawing countless visitors each year. Yet in the laneways his characters haunted and the bars he wrote about, few people seem to care about him. I wondered, is Joyce even relevant to the city any more?

Even the woman scheduled to give me a walking tour of Joyce’s Dublin was skeptical. “You really want a Joyce tour?” she asked, when I met her in the lobby of my hotel. I confess, I was relieved. After a few days in the city, I’d had enough of the old fellow, whose sour face is everywhere, on buildings and in shop windows, and whose quotes adorn the walls of taverns and countless sidewalk chalkboards. I was quite happy to take up her offer of a more general meander.

As we wandered east along the River Liffey, lined with stunning old Georgian buildings rivalling any in Europe, my guide suggested we see the new Dublin Docklands development. To get there, we crossed the soaring Samuel Beckett bridge, completed in 2009. On the other side, we twisted and turned and emerged into Grand Canal Square, a public space designed by Martha Schwartz that is lined by the canal and vaulting, hyper-modern buildings by Daniel Libeskind.

A street fair was under way, with food trucks and a sad little carousel. Men sold balloons and you could play carnival games with numbered floating ducks, as likely to drain to your wallet as the tourist-packed bars of the Temple Bar district a few kilometres away, where a pint of Guinness might set you back €7.

On the canal, a water-skiing competition was taking place, the announcer’s voice booming across the square. People applauded and ate tacos. It felt modern and fresh – a lifetime (or perhaps just 100 years) away from James Joyce.

To find out if anyone still liked him, I asked the person I thought most likely: Thomas Morris, the newly appointed editor of Ireland’s premiere literary magazine, The Stinging Fly. His own debut collection of short stories is due out next year. He’s also the editor of a fascinating new book, Dubliners 100, in which 15 contemporary Irish writers “remix” one of the stories from Joyce’s original version.

I met with Morris at Grogan’s, a beloved pub that he described to me in an e-mail as “filled with the oddest people (in the best sense).” I tucked into my 32nd-or-so Guinness of the trip while Morris, feeling a bit under the weather, had a “hot whisky.”

I asked him why he’d decided to celebrate Dubliners, a book in which Dubliners seem uninterested.

“It had been my feeling that outside of universities, there was a great deal of empty gesturing towards Joyce and Ireland’s literary history,” he said. “People talked about Joyce and held him up as an important figure; they dressed up for Bloomsday and spouted crap about his legacy, but yet there seemed to be very little attention given to the work, especially to Dubliners.”

The new takes, he hopes, will show that there are creative ways of marking a book’s importance, as well as “remind people that Dubliners is a bloody good book that deserves revisiting, and highlight the fact that, as well as a literary past, Ireland has a vibrant literary present.”

He was not the only true believer I met. One morning near the end of my stay I made my way to Sandycove, a muted suburban beach village, where Joyce lived briefly in a Martello tower, dozens of which dot the Irish coast. This particular one is immortalized in the opening scene of Ulysses and is now the James Joyce Tower and Museum.

There I met the museum’s curator, a gentle, mustachioed man named Robert Nicholson, who showed me the small but fascinating collection he’s assembled since taking up his post in the 1960s.

There’s a beautiful vest adorned with deer and dogs, given to Joyce by his mother, and a tie donated to Nicholson by Samuel Beckett, which Joyce, a fancy dresser, had given him in Paris. First editions, quotidian objects that are mentioned in Joyce’s work, illustrations of the author: It’s a ramshackle yet charming collection. Being in the tower was the first time on the trip when I had a sense of Joyce being represented as a living, breathing idea, a messy life converted into a force that continues to resonate, rather than a concept turned museum piece, collecting as much dust as tourist dollars.

From the roof of the tower, we saw the coastline spreading in front of the town, and, to my great surprise, people descending what looked like stone steps into the nearby Irish Sea.

“I swim almost every day of the year,” Nicholson told me.

On my way back to the village, I could not resist. I descended to what I later learned is a legendary swimming spot called Forty Foot, removed my shoes and clothes and, gingerly, in my boxer shorts, walked down the freezing, wet steps to the sea, steadying myself on a feeble iron railing. I jumped in. I screamed. I thrashed about a bit. I jumped out. I later learned the water that day was nine degrees.

Afterward, I threw my wet boxers away, slapped on my clothes and made my way back up the steps to a little lane, where Nicholson was hustling by, umbrella in hand.

“I went in,” I said proudly, teeth chattering.

“Yes,” he replied. “I spotted you.”

Later that night, I walked through Smithfield, a working-class neighbourhood on the western side of city centre, in the shadow of the massive Jameson whisky distillery. Down an alleyway labelled Coke Lane, I noticed a bar called Frank Ryans, which looked like my kind of place – slightly grubby, neon signs – and indeed it was: a dark, long room crammed with bizarre memorabilia, its ceiling strung with shoes hung from their laces, men’s and women’s underwear, abandoned brassieres. It wouldn’t be out of place in a special Dublin-set episode of Twin Peaks.

As I settled into a warming whisky of my own, I looked at the dozens, perhaps hundreds, of framed photos on the wall. A huge number of them featured the same person, a man I did not recognize with a sad, youthful face, thin mustache and a poof of black hair. Eventually, I got up and investigated. They were all photographs of Phil Lynott, the Dubliner who played bass and sang in the legendary rock band Thin Lizzy. Lynott died in 1986 at the age of 36, his body destroyed by years of drug abuse.

Gazing into dozens of portraits of the artist as a young man, I felt relief. Here, in the middle of Joyce country, I’d uncovered an elaborate shrine to someone else, someone more recent – perhaps even more relevant, and certainly, in this room, more beloved.

Cities change, and no identity, no matter how many tourists it draws, can represent a people and a place indefinitely. In the eyes of the world, Dublin belongs to Joyce. But on that night in Smithfield, Phil Lynott was back in town.

IF YOU GO

Where to stay

The Morrison Hotel: A renovation has turned this hotel into a shrine to Irish musicians – song lyrics decorate the walls and music thrums in the lobby. The location is unbeatable, steps from the River Liffey. Rooms from €260 ($382.30). Ormond Quay; morrisonhotel.ie

Where to eat and drink

The Winding Stair: Spectacular contemporary Irish cooking in a stately old room above a bookshop. 40 Lower Ormond Quay; winding-stair.com

Dunne and Crescenzi: Tired of meat and potatoes? Head to this Italian spot, with excellent fresh pastas. 16 Frederick St. S.;dunneandcrescenzi.com

The Stag’s Head: This bar came strongly recommended by The Globe’s John Doyle and Cathal Kelly, two men who know their bars. A quintessential pub experience. 1 Dame Court;louisfitzgerald.com/stagshead

What to see

The Book of Kells: The ninth-century illuminated manuscript is breathtaking, but better still is the library above it, a beautiful shrines to literature. Trinity College; tcd.ie/Library/bookofkells

The James Joyce Tower and Museum: A labour of curatorial love, this museum puts you as close as possible to the writer. jamesjoycetower.com

The writer travelled with assistance from Tourism Ireland. It did not review or approve this article.