10 minutes

10 minutes

The clock had run down for Gord Pederson. His pub, Longshots, had survived the frenzied oil sands boom but was now being evicted and shuttered – a victim of a push to overhaul Fort McMurray’s tired downtown.

The drive for downtown renewal is a hallmark of a city that had exploded in growth over the past decade as the oil sands surged, widening a divide between those who like Fort McMurray the way it is, or was, and those with more grandiose plans. A 2012 city urban renewal plan laid out a vision for high-density development, bike-friendly streets, skyscrapers and retail – using aspirational photos from Vancouver, Portland, Toronto, Brisbane and other cities. Fort Mac was dreaming big.

This is a classic boom town saga, featuring stunning growth, seat-of-the-pants planning and now a quintessentially Canadian solution – visions of a gleaming new arena, hotel and casino complex – all against the shaky backdrop of plunging oil prices that have undercut the very basis of the boom.

The city has spent $48-million snapping up prime core land, evicting tenants and razing buildings – in some cases using expropriation to force the plan through. Following complaints about how the land was being procured, two officials – one a bureaucrat and the other a consultant – left town in the midst of an audit that found Fort McMurray’s administration was something of a Wild West. It uncovered a spotty paper trail and a murky chain of authority.

Longshots was a goner in October, 2013. Other bars, a hotel, the former Fort Theatre, a law office, an oil company office, restaurants, a music store, non-profits and other businesses have since followed, or will, all clustered in the city centre.

But nearly all the land is now empty, and council has since seen oil slide below $50. Capital budgets in the burgeoning community are already stretched and the main bidder on the project last month asked for more money, sources say.

One landowner whose property was expropriated is a current MLA, though he says the deal has badly hurt his business. With the downtown ordeal top-of-mind, voters went to the polls in 2013 and turfed five incumbents. An expropriation inquiry ruling later said the city plan was “not sound” and was unfair.

“There wasn’t a whole lot of thought put into this, whatsoever,” said Keith McGrath, one of the new councillors who won a seat amid unrest over the project.

While trying to revitalize the downtown core, the city has so far done the opposite – gutting a prominent block in the heart of town, forcing out businesses like Longshots.

“Put it this way: It’s frustrating to me to see it sitting empty. And I’ll let people read between the lines on that, because everybody knows there’s reasons why it’s sitting empty,” said Mr. Pederson, who had to sell his restaurant equipment for 10 cents on the dollar. “Maybe if things had been done differently before, during and after, we’d still be there.”

Tale of two cities

There are two Fort McMurrays – the fly-in, fly-out crowd who come and go with the price of oil, and those here for the long haul. That first group may not come back this year, amid $50 oil, layoffs and billions in deferred capital spending. But the second group is still here and has grown weary of being seen as a boom-town outpost. Many support doing something about the neglected downtown.

A plan emerged with the February, 2012, release of the municipality’s City Centre Area Redevelopment Plan, or CCARP, spearheaded by a Toronto-based consultant, Ron Taylor, who’d been brought on in mid-2011. The goal of Mr. Taylor and the municipality’s highly paid top bureaucrat hired the year before, CAO Glen Laubenstein, was to build an arena.

The CCARP is a 96-page document with few concrete details, instead pledging to turn Fort McMurray’s downtown into that of Vancouver or other cities. On three occasions, the document also refers to a downtown arena. No specific block is indicated, but for Mr. Laubenstein – whose past experience left him familiar with arena projects in other cities, including Winnipeg and Kingston – and Mr. Taylor, the plan was something of a starting pistol.

On behalf of the city, they began buying land, but not on any particular plot.

The first deal to close, in March, 2012 – a month after the plan was released – was the Oil Sands Hotel, an institution though one with precisely the sort of seedy underbelly that fed the negative narrative. One criminal lawyer said in an interview that he supports the revitalization but, half-jokingly, lamented that closing the Oil Sands Hotel, with its two bars and a strip club, cost him business. The purchase took some city councillors by surprise; they learned about it only afterward. The arena was moving ahead without them.

“When I questioned it, I was told, well, we have money in the budget for land purchase,” Councillor Jane Stroud said. “It made it difficult to pursue [the issue].”

Nonetheless, the Oil Sands Hotel was bought for $7.7-million by a cash-flush municipality with $700-million in annual revenue, largely from oil sands projects that are within its sprawling borders.

Despite the hotel purchase, an arena site hadn’t been picked. By Bob Barrett’s recollection, he began getting inquiries about his building on the next block in 2012 – at first from a builder, then the city. He stood to lose his building, his retail tenant and the storage he used for another business. “Were they willing to ante up, they could talk to me. But they weren’t willing,” Mr. Barrett said.

The land buying quietly continued. The city bought an empty theatre across the street from Mr. Barrett’s and, eventually, the Longshots building behind him – pinning him in. “It was handled very poorly,” Mr. Barrett said.

Council, meanwhile, was unclear on much of this. In interviews last month, some said they didn’t know key details of the arena project. Councillors also could not say when a site was selected, nor could Mr. Laubenstein or his successor, Marcel Ulliac. Councillors say it was the administration that led the land buying, with few public updates due to the confidential nature of the bidding process. But, at some point, they pushed ahead with the original block, the one with the Oil Sands Hotel – and a building next door, owned by Mike Allen.

Mr. Allen, while a municipal councillor, had been in talks with the Oil Sands Hotel owners to sell privately, together, before the municipality came knocking. Once it bought the hotel, the city wanted his building, too. Mr. Allen says he wanted any deal to include relocation of his business, Campbell’s Music, and other non-profit tenants. But talks with the municipality fell apart, he says, and it expropriated instead.

The city paid what Mr. Allen says he had already agreed, in theory, to sell for – roughly $4.5-million – on a building he’d paid $1.15-million for in 2006. Some non-profits were moved and the city also agreed to move Campbell’s Music to another building it had bought, emptied and renovated nearby at a cost of just over $4-million. Similar to Longshots, that building was near, but not on, the arena site.

The lease between Mr. Allen’s business and the municipality, obtained by The Globe and Mail under freedom of information laws, shows Mr. Allen will pay $141,700 a year, or $25.60-per-square-foot, over a five-year term. Market rates in Fort McMurray are typically at least $40, and often well above that, say several people familiar with the city’s retail sector.

Mr. Allen said the city was simply obligated to charge him what his business was paying already in his building, or pay the difference if he found a new lease on his own. He soon faced local anger over rumours of the deal, and was bound by a gag order in the lease from discussing it publicly – one he asked the municipality to lift, and says it refused.

He also produced a letter from Alberta’s Ethics Commissioner, clearing him of a conflict as an MLA in the sale, and says the city assessed his property’s value last year at $7.5-million, well above what he was paid in expropriation. He will seek re-election and still supports the arena. “It was about improving quality of life,” he said. “It was about improving Fort McMurray, the downtown.”

Other businesses fought their expropriation, including The Keg restaurant, which was losing its parking lot; A&W, which would lose its entire building and a drive-thru on prime land; and a law office that also housed French energy giant Total’s modest office.

That triggered an expropriation hearing that produced a ruling that said there was no evidence the city closely studied whether the block it was now pursuing was suitable for an arena – no evidence of transportation, parking or utilities studies, for instance – and that the city “did not proceed fairly.” But the ruling was non-binding and the city pressed ahead.

By the time the 2013 election rolled around, the fight had gotten messy, particularly with expropriation. The new council came in and, amid the outcry, later brought in an auditor, KPMG, which began its work in April, 2014. Mr. Taylor’s contract was terminated that month, and Mr. Laubenstein resigned the next month as the audit continued, a municipal spokesperson said.

Mr. Laubenstein declined to comment on the circumstances of his departure.

“The reality is whenever you’re making the kind of changes being made there, there’s three sides to every story, and there’s people who stand to benefit from the change and people who stand to be hurt from the change,” he said. “And that’s downtown development in just about every city I’ve ever seen.”

The final KPMG audit was critical of the municipality, saying broadly that the community, in its growth, didn’t have proper records or checks and balances on spending, travel and other matters. On the arena, in particular, it found no documentation of any conflict-of-interest checks, no evidence of a paper trail on expropriation, and that some land purchases were only “completed and approved verbally.” It did not find criminal wrongdoing, but blamed a lack of “tone from the top.”

Mr. Taylor did not respond to several interview requests.

Several council and city officials in interviews welcomed the findings and pledged action, though not all thought the audit worthwhile. “It says we don’t push enough paper on our stuff.… There’s nothing there,” said Councillor Allan Vinni, a lawyer.

Mayor Melissa Blake is Fort McMurray’s only full-time elected municipal official. Ms. Blake, who was mayor when the expropriation began and was re-elected in 2013, said she stands behind the votes she’s made on council, but distanced herself from the audit’s finding. She suggested “tone from the top” refers to the administration, not her, raising a question of who is in charge.

“The council tries to make it about me, but I’m going to tell you the top is not me,” she said. “The top is the leadership that’s there.”

Stumbling Block

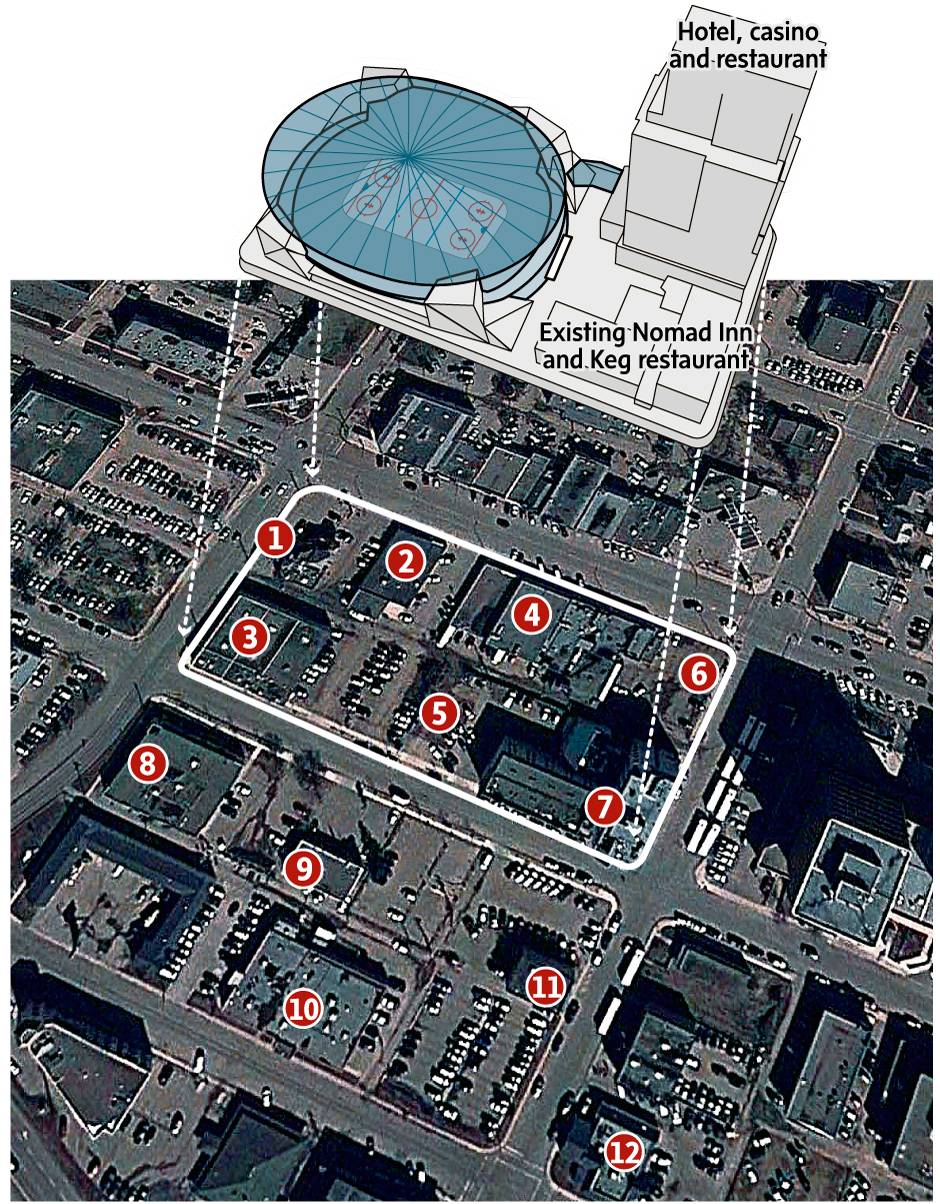

Some information is emerging about the project. The arena is a 7,500-seat facility poised to take up nearly an entire block. It will be built first, aimed possibly at a minor hockey team tenant; the proponent hopes an AHL-level team, one step below the NHL, could be wooed, while others have their doubts. It could also host other events like concerts and trade shows. After it’s built, a hotel and casino will go up next to it and eventually a 480-stall parking garage across the street, said Ted Zlotnik, the municipality’s director of supply chain management.

He acknowledged much of the information has been kept secret, amid a proprietary bidding process. He hopes that will change within a month. “We hope we can get to a signature on the letter-of-intent shortly and move to a public engagement process as soon as possible,” he said.

However, one building on the block is unaffected: the Nomad Hotel, which also houses The Keg. The hotel is owned by a group that is also leading the Clearwater Consortium, the top bidder for the arena. Clearwater’s parent company, Shelter Canadian Properties Ltd., donated $2,000 to Ms. Blake in the 2013 election, though CEO Arni Thorsteinson said it had no impact on the outcome. Election records show the company did not donate to any other candidates. “That’s part of the political process,” Mr. Thorsteinson said. “We always encourage and financially support candidates seeking public office at all levels, municipal, provincial and federal.”

Mr. Zlotnik echoed that, saying it was the administration that recommended Clearwater’s bid to council, though Ms. Blake did not recuse herself. She said she isn’t aware of everyone who donates to her.

The proposed deal, made public in the fall, would see Clearwater build the arena on city land, taking on all the risk and potential profit in exchange for, as of October, $7.6-million in city funding annually over 30 years. Clearwater would also buy the Oil Sands Hotel site to build, run and own a hotel and casino. In a closed-door council meeting on Jan. 20, though, Clearwater asked for more money before a letter-of-intent can be signed, roughly $9.5-million annually, sources say. Mr. Thorsteinson declined to say whether his bid was seeking more money.

Amid it all, the price of oil has dropped – and could take with it growth projections that might have underpinned the justification to spend millions annually to subsidize an arena. Now council is left negotiating a letter-of-intent in private, with doubts about whether it will proceed.

“Here we are now, coming to almost two years we’ve owned these buildings, lost this revenue, people lost their jobs, and we’re nowhere closer today to actually utilizing these lands than we were when we first voted them out,” said Mr. McGrath, the new councillor.

So councillors are left with a decision – bow to Clearwater’s demand for another $60-million over the term of the deal, pick another proponent, or walk away and start over. And, if they walk away, they’re stuck with empty land and could face legal fights over expropriations that, in the end, weren’t needed for a public purpose.

In the frenzied, oil-cash-fuelled bid to overhaul their downtown, that land was bought at a premium. Some councillors doubt they could sell it for what they paid. “That’s the multimillion-dollar question, I think,” Councillor Tyran Ault said. “If it doesn’t go forward, we’re in a tough spot, because we have to play with the cards we were dealt as a council.”

Some people, including the mayor, still support the arena.

“The process has been awful,” said Councillor Sheldon Germain, one of the councillors to be re-elected. “… I’m scared it’s actually marred a very good idea, which is a sports and entertainment centre.”

In the meantime, several businesses are stuck in limbo. A Unifor union office, jewellery store and Mr. Barrett’s tenant, a men’s wear store that bears his name, face the prospect of being pinned in between the currently empty Longshots site, which is said now to be used for construction equipment, and the arena construction site. That disruption could hurt his business, Mr. Barrett said. He, like the rest of Fort McMurray, is waiting to see what’s next.

“This was a huge leap to change the downtown core into something. And it got trapped in the way they tried to make it happen,” Mr. Barrett said. “…They tried to say the public is never going to be happy with it 100 per cent anyway, so ram it through.”