Caity’s life of addiction in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside was transformed after a Vancouver clinic treated her with suboxone.

When Caity showed up at St. Paul's emergency room last October, she was in rough shape.

The young woman – The Globe and Mail has agreed to not use her last name – was at the time living on the streets in Vancouver and addicted to illicit drugs, including heroin and pills likely laced with fentanyl.

She said she wanted help. ER staff called Dr. Mark McLean, who was on call for St. Paul's Rapid Access Addiction Clinic, which runs out of a small room one floor above the ER.

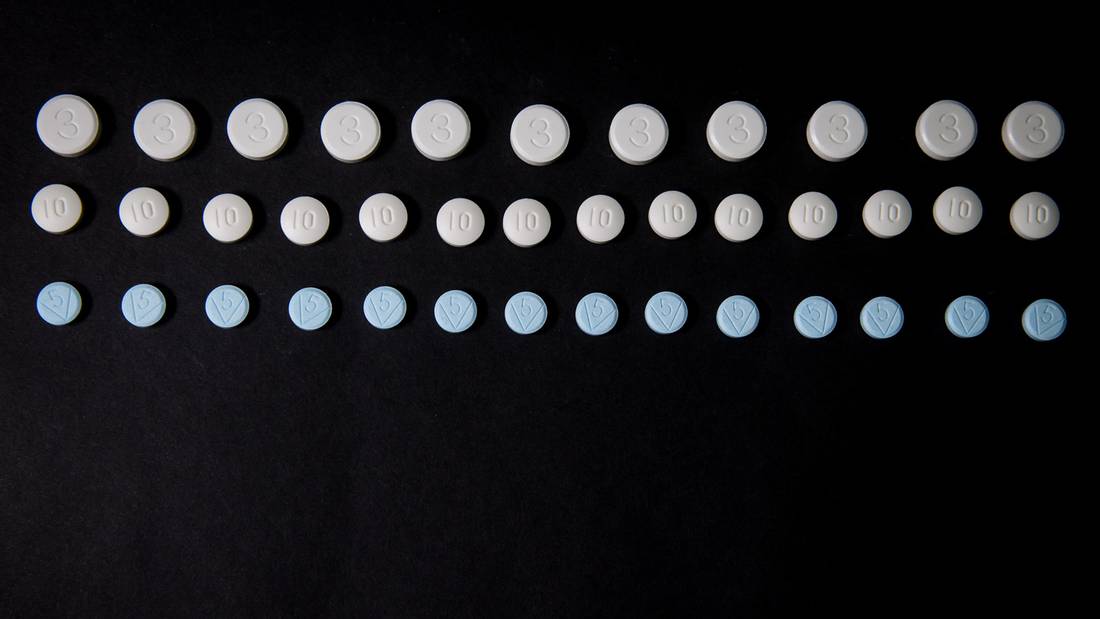

Dr. McLean said Caity should come back to see him at St. Paul's the next morning when she was in full-blown opioid withdrawal, so he could start her on Suboxone, the trade name for a pill composed of buprenorphine and naloxone.

That's what happened – in large part because her parents, who'd come to Vancouver to help her, made sure she came back on time. Now, three months later, Caity is sober, living with her parents and taking a daily dose of the treatment, which she says has transformed her life and given her hope for the future.

She wants other people to have the same chance.

"It was amazing, because I went from the worst agony of my life to absolutely normal," Caity said in a recent telephone interview from her home in Interior B.C.

Caity's experience provides a textbook example of what the Rapid Access Addiction Clinic was set up to do: provide treatment, as quickly as possible, to people addicted to opioids or other substances, including alcohol. Other community clinics – including the Mobile Medical Unit operating in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside since December – have embraced the same model. Her story also highlights the potential benefits of drug treatments that experts say should be key in tackling an overdose crisis that killed nearly 1,000 people last year in B.C. alone.

For Caity, now 23, the clinic was a turning point on a perilous road. As a teenager, she enjoyed goofing around with friends and spending time with her family. She started using drugs when she was 19. Cocaine and "oxys" – OxyContin – progressed to injection heroin. She overdosed several times, once in the basement of her family home, where she came to after her father gave her CPR.

She came to Vancouver, where she drifted between the Downtown Eastside and a stretch of 135A Street in Surrey known as the strip and renowned for open drug use, poverty and homelessness. Her parents struggled to keep in touch, at one point not hearing from her for more than 30 days. Her father made several trips to Vancouver to check on her and give her small amounts of cash, phones or phone cards, which were invariably lost or stolen. He was by turns worried, angry and despondent, at one point telling himself that his next trip would be to identify her at the morgue.

But they pushed Caity and pushed the system, pressing police to keep an eye out for her and looking for programs that could help. At one point last year, they signed her into a treatment centre in Vancouver but she didn't stay.

Then, in October, her parents made another trip to Vancouver. They found Caity and took her to St. Paul's because she had an abscess on her thumb. (Abscesses are a common complication for injection drug users.) The ER doctor on duty remembered her from a previous visit and, after speaking to her and her parents, thought she might be a good candidate for treatment and called Dr. McLean at home.

The pieces came together. Caity was soon stabilized on Suboxone and her parents feel they have their daughter back.

"Caity finally got to that point where she wanted to get out of Vancouver, and off the streets and wanted to get help," her father says. "All of those things lined up. But there are thousands of people who would like to do it, but who don't have the support – whether that is family, or institutional things."

Taken orally, the buprenorphine and naloxone combination works by reducing withdrawal and cravings. With methadone, Dr. McLean says, dosages have to be increased gradually to avoid risk of overdose and it can take up to six weeks to get patients to the point where they are stable and free of cravings.

With Suboxone, he can stabilize patients in a day or two.

Because patients have a lower risk of overdosing compared with methadone, patients can get take-home medication, or "carries" sooner.

British Columbia has been a front-runner in making buprenorphine/naloxone more accessible. The province added Suboxone and its generic equivalent to its drug formulary last year, meaning those medications are paid for under the provincial drug plan. Also last year, regulations were changed so that B.C. physicians no longer need an exemption under the federal Controlled Drugs and Substances Act to prescribe them.

Dr. Mark McLean, left, and addictions registered nurse Sherif Amara, right, talk with patient Daniel Lagrois at St. Paul’s Hospital, in Vancouver.

DARRYL DYCK/For The Globe and Mail

This month, B.C. said it would provide full coverage for opioid substitution therapies through a drug plan for people with low incomes.

As of December, 2016, according to a review from the B.C. Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, buprenorphine/naloxone was listed in the provincial drug plan formularies for all 10 provinces. (Data for Nunavut, Northwest Territories and Yukon were not included in the update.)

But only four provinces – B.C., Alberta, Ontario and Nova Scotia – do not require special authorization for the drug to be prescribed. And all provinces require or recommend documentation of doctor training prior to prescribing.

This week, B.C. Health Minister Terry Lake said about 500 doctors and nurse practitioners in the province have been trained in prescribing buprenorphine/naloxone over the past six months.

Last year, 6,800 patients in B.C. received Suboxone or its generic equivalent and 18,200 patients received methadone, says the Ministry of Health. (Those numbers are not mutually exclusive as some patients would have switched from one therapy to another throughout the year.)

The number of people receiving treatment for opioid addiction has climbed by 52 per cent since 2011, the ministry says.

A 2016 report by the B.C. Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and CRISM, the Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Misuse, cited the experience from other jurisdictions where the drug is more widely available.

In France, where all registered doctors have been able to prescribe buprenorphine/naloxone since 1996 without specialist training or licensing requirements, opioid-related overdose deaths have declined about 80 per cent since 1995, the report said.

The Rapid Access Addiction Clinic is nothing fancy. There's a room furnished with five reclining chairs, where patients can sleep. The room has a computer and a phone and a television will likely come soon. It's a place where people who are not sick enough to get a bed can stay, under medical supervision, until they have been stabilized on opioid treatment.

Patients are referred from the emergency room at St. Paul's or from community health centres. In some cases, they seek it out.

Clinical nurse leader Nancy Chow believes the clinic is unique to hospitals in Vancouver and hopes other facilities will follow suit. "If we give another option, and have another place that's a little bit more comfortable to stay, and have the immediate attention, that could be increasing the access to treatment," Ms. Chow said.

The clinic opened Sept. 26, staffed by two nurses and a physician, and with help from peer navigators and social workers. Its goal is to provide treatment within one or two days of a referral.

Caity's father understands the difference small changes can make.

When he brought Caity back to the emergency room last October, she wanted to sleep, but couldn't stay upright in a chair. A sympathetic nurse offered a bed, but staff soon reclaimed that for patients with more urgent medical needs. Security staff said she couldn't sleep on the floor. With her parents keeping watch, Caity took some blankets and curled up under a bus bench outside, where she stayed until Dr. McLean came to meet her.

"To have a nice room where they could just sleep and not be bothered when the doctor comes in – these are just the little things people are not aware of," Caity's father said.

People can stay on the buprenorphine-naloxone combination indefinitely. The idea is for the medication to be a safety net for people as they get their lives back on track.

For Caity, Suboxone has allowed her to reconnect with family and friends. She's thinking of going to school, and talks about being a psychiatric nurse and sharing her experience with families and young people.

For Dr. McLean, the clinic brings a measure of optimism amid a sea of discouraging news.

"For me, the most exciting part is the variety of different types of addiction problems that patients bring to us," Dr. McLean says.

"Many of the patients who come to us do have moderate to severe addiction. And we are finding that it is possible to intervene successfully. We are stabilizing patients. Many patients have had problems for a long time that have been hard to control and we are indeed making an impact on that part of the population."