On a Sunday morning, the tanker Eser K idled in Burrard Inlet, off of Kinder Morgan's Westridge Marine terminal in Burnaby, B.C. The ship had just loaded 356,626 barrels of Alberta crude oil, destined for California.

Deckhands prepared to weigh anchor, their departure timed so that the ship would cruise under the Second Narrows rail bridge at the precise moment that the currents were neither pushing nor pulling: Slack tide.

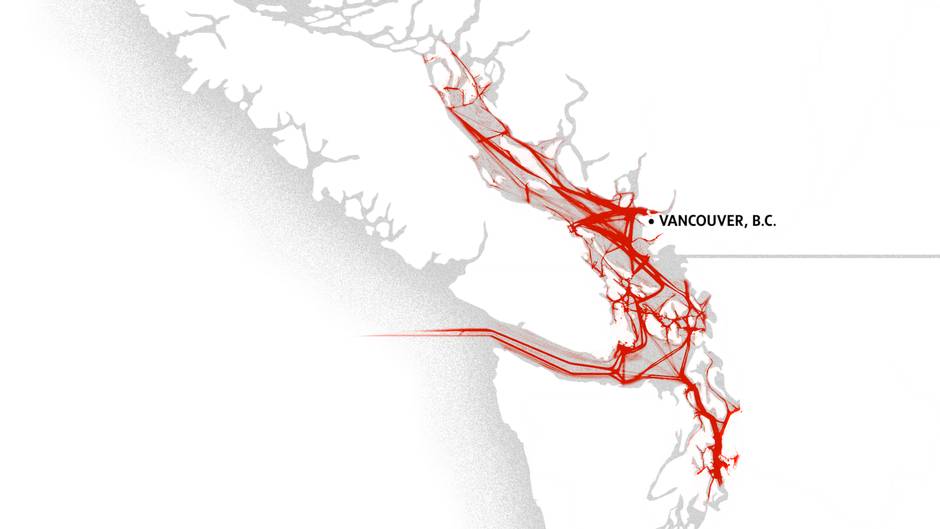

The roughly 250 large commercial vessels that enter the Port of Vancouver each month do the same, but Kinder Morgan's Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project, approved by the federal government last November and now at the centre of the delicate negotiations over the future of British Columbia's minority government, has put oil tanker traffic off the province's coast in the spotlight.

The company hopes to begin construction this fall, although the decision is on hold until the company has all the financing is in place. The project would triple Kinder Morgan's oil shipments from Cold Lake, Alta., to the coast and the expanded capacity would mean a sevenfold increase in the number of oil tankers leaving the terminal to make the passage through these narrow, busy waterways.

According to Kinder Morgan, the risk of a major oil spill on this route is small. A major spill, as defined by the company, would be one 3,000 times larger than the Marathassa spill in English Bay in 2015 and is a once-in-473-years event. But critics say the risk has been dramatically underestimated.

The City of Vancouver, in its submissions to the National Energy Board, tabled a report showing the risk of a marine oil spill in the 50-year life of the project is between 16 and 67 per cent. The city argued the risk is too high because a spill could cost the economy hundreds of millions of dollars, and the environment would be devastated with the deaths of more than 100,000 sea and shorebirds. Harbour seal and salmon populations could be decimated, and the endangered southern resident killer whale population would be at risk of extinction.

The Concerned Professional Engineers, a group with expertise in the design, construction, and operation of the systems for moving marine goods such as oil, said even using Kinder Morgan's data translates into a 10-per-cent chance of a 8.25 million-litre heavy oil spill over the project's operating life. However, they say that figure is conservative because the risk of a tanker colliding with one of the three bridges along the route in Vancouver's harbour have not been adequately calculated.

The Globe and Mail followed the Eser K through the most hazardous stretch in B.C. waters, a 10-hour journey spanning 80 nautical miles, to observe those risks and the mitigation measures in place.

The Westridge Marine Terminal is seen on the right.

Jimmy Jeong/for the globe and mail

On the morning of Feb. 5, two Canadian pilots, assigned by the Pacific Pilotage Authority, boarded the Eser K to take command of the vessel until it passed Victoria. The ship is flying a Marshall Islands flag and the international crew may have little experience in these waters. Canada requires locally-trained pilots to be in the wheelhouse on commercial vessels of this size, to direct the ship's course and speed from the port of Vancouver out to Brotchie Ledge, near Victoria.

The port of Vancouver is the most active in Canada. Ice-free and deepwater, it is home to terminals for oil, chemicals, containers and bulk goods, as well as a cruise ship terminal. For vessels as large as the Eser K, a tug escort is mandatory in addition to the pilots, and two Seaspan tugboats, the Raven and the Kestrel, were tethered to the 250-metre-long Aframax class vessel – the largest oil-tanker class allowed in the port – before the massive anchors were hauled in.

Once the ship was loose, the pilot's voice came across the radio on the bridge of the Raven: "Show us what you can do." Butch Peever, at the helm of the Raven, twirled a dial on his console and the engines hummed. The 30-metre long tug with 5,000 horsepower engines nudged the Eser K around to face the twin spans of the Second Narrows rail bridge and the adjacent Ironworkers Memorial bridge.

Captain Peever has served on tugboats on these waters for 40 years, and has worked tanker escort runs since 2001. He has dealt with engine failures, steering failures, "a couple of instances when things have got tense," but no major mishaps. "I've been pretty lucky."

The crew of five will live aboard the Raven for a week at a time, working in six-hour shifts as engineers, chefs, deckhands and masters. Technological advances have improved marine safety, but the changes have also allowed companies to whittle down the size of their crews.

Just east of the Second Narrows lies the narrowest corridor on the route. Although there appears to be ample space between the shores, a man-made obstacle lurks below the surface, a line of loose rock that has been piled up to serve as armour for a municipal water line.

Passing the Second Narrows railway bridge is a carefully calibrated move, said Robin Stewart, vice-president of BC Coast Pilots. "There is a defined edge, at the rail bridge, of 138 metres. The rest of the channel [depth] varies greatly depending on the height of the tide. The area around the water line presents the least amount of channel, so it is there that defines if the vessel can transit or not." The Eser K requires a clear channel 125.4 metres wide to safely pass, but that can change depending on the tide, or how shallow the ship is sitting in the water. "If there is not enough tide, we do not sail the vessel."

Thirty years ago, larger ships would be allowed in these waters without tugs or modern navigational aids, he noted.

But the Exxon Valdez disaster changed everything.

In 1989, the oil tanker Exxon Valdez struck a reef in Alaska, releasing 44,000 tonnes of oil. The Canadian government rewrote the rules to improve shipping systems to reduce risk, to improve spill response, and to ensure that industry was responsible for the costs.

The pilots gauge the ship's clearance in all directions, including space for the tugs to manoeuvre, the draught of the hull below the waterline, and the air draught – the distance from the surface of the water to the highest point on the vessel. Clearing all those points under the span of the bridge is a bit like threading a needle, and the harbour master allows only one tanker through at a time.

These precautions reflect the risk. The Concerned Professional Engineers group notes that this bridge has been knocked out of commission five times because of ship collisions. Aframax tankers like the Eser K are five times heavier than the largest of those vessels, and the group estimates that such a vessel could knock the bridge right off its foundations and carry the bridge superstructure into the adjacent highway bridge that lies 110 metres to the west.

Vice-president of the B.C. Coast Pilots, Robin Stewart, poses for a photo while on escort of the Eser K oil tanker.

Jimmy Jeong/For the globe and mail

Between the Second Narrows and the Lions Gate bridge, the Vancouver harbour is alive with pleasure craft, container ships, SeaBuses and float planes landing and taking off. The Eser K moved slowly, towering over most other vessels. At the Lions Gate, the traffic narrows again and no other ship was allowed through while the Eser K slid beneath, into English Bay.

A recent oil spill in English Bay provided a vivid reminder of how difficult any cleanup would be. In 2015, the cargo ship MV Marathassa spilled 2,800 litres of bunker fuel while at anchor in the bay. Despite ideal weather conditions and close proximity to an oil spill response base, it is estimated that only half of the fuel was recovered. An independent review described the incident as "an operational discharge of persistent fuel oil with very high consequences."

Det Norske Veritas is an international independent agency that provided a risk analysis of the Trans Mountain project for Kinder Morgan. The company looked at what could go wrong, from a ship-to-ship collision to a fire on board the vessel. They pinpointed several locations most likely for an oil spill to occur, and despite the high traffic, the authors concluded that collision with another ship in English Bay was a low probability.

However, Det Norske Veritas did indicate there is a risk of a collision with another vessel out in the open waters past Roberts Bank because of the frequency of ferry traffic and the traffic crossing from the Fraser River. This, though, is where the safety restrictions imposed by the port are reduced.

As the Eser K headed past the emerald green point of the University of B.C. lands, it picked up speed to 13 knots. The Seaspan Kestrel tug peeled off, its escort duty complete. The pilots radioed over instructions to the Raven to begin a training exercise – a rare opportunity to practise controlling the ship from the tug.

It was now Capt. Dave Dawson's shift. The Raven was tethered at the stern of the tanker by a cable that is rated to pull 300,000 lbs. The Raven swung out to port, and then starboard, changing the tanker's direction. As the Raven pulled to each side, it keeled over to 15 degrees, its black bumper rails kissing the waves. Capt. Dawson focused on keeping his cable taut, but the chef in the galley cursed as lunch preparations bowled around.

Out on the Strait of Georgia, the next stretch was 35 nautical miles of open waters. The tug's tether was dropped and the Raven paced the Eser K.

"Right now we have snow squalls, we have a gale, probably six-foot waves and we have less than a half a mile visibility," said Capt. Dawson. "Yeah, that's more like it. I do like routine but it's also fun to get a little bit of – snow showers? I can't believe this winter."

Jimmy Jeong/for the globe and mail

After a bouncy crossing of the strait, the tug resumed its tethered escort duties as the two vessels entered the stretch between British Columbia's Gulf Islands and Washington State's San Juan Islands.

This is the turn point at the Arachne Reef and Des Norske Veritas warns this is a dangerous junction. "Possible powered grounding is a low probability event due to pilots and tethered tug," the report states, "but this location is rated with greatest level of navigational complexity for the entire passage. Location also has high environmental values."

The Eser K lowered its speed, winding through Boundary Pass and then Haro Strait. By now, the dark of an early winter evening had set in. Keeping the tug crew busy, the pilots used the Raven at times to steer the tanker around the islands.

Near the end of the trip, the tug's master swung the Raven out to port as instructed, but was visibly anxious because in the dark and with the blowing snow, he could not see if the cable was wrapping around the Eser K's stern. Capt. Dawson returned to the bridge, threw a spotlight on the line and the tug adjusted its position, manoeuvring the tanker on a line into Juan de Fuca Strait. This is the kind of experience that isn't replicated in the computer simulations that pilots usually train on.

Capt. Stewart of the BC Coast Pilots joined the crew on the Raven to answer questions on the trip. Before he departed, he said he was proud of his relatively uneventful career. "There's nothing flamboyant about success; there are not a lot of sea stories to tell about successful voyages."

Capt. Stewart, who served 22 years as a captain tug master before becoming a pilot, said his team brings a deep knowledge of the local waters, as well as specialized equipment and training, to their work. But it's also a passion for this marine environment that keeps them sharp. "We were raised on this coast. You take it so seriously because we know we have so much to lose."

Tug boat captain Werner Klein on the evening shift while escorting the Eser K oil tanker from the Kinder Morgan Westridge Marine Terminal.

Jimmy Jeong/for the globe and mail

As the ships passed the city of Victoria, a pilot boat pulled alongside the Eser K, matching its speed. The pilots descended a gangway part of the way down the steep side of the ship, then hopped over to a ladder dangling down to reach their own vessel.

The ship was approaching the final risky point, according to Kinder Morgan's risk analysis. In the Juan de Fuca Strait at Race Rocks, where the marine weather can be strong, a collision with another vessel was determined to be a low probability but possible because not all vessels in this location have a pilot aboard.

But this is where the Raven ended its escort duties, and the Eser K made its way out toward the Pacific alone.

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL: