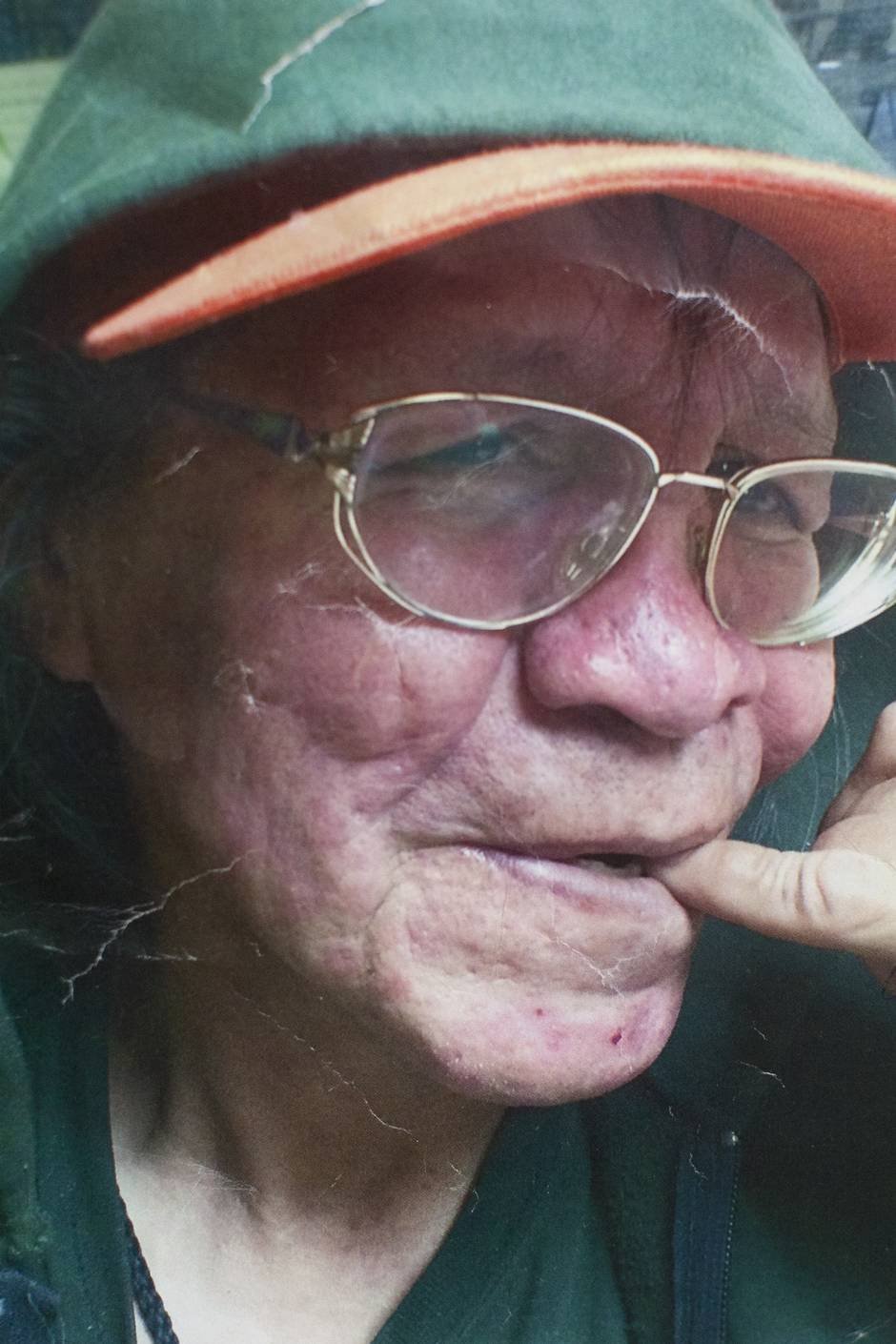

Lorna Bird pages through the notices of friends gone too soon: dozens of crinkled papers, poor-quality photocopies, torn edges. Such notices used to go up on the office wall, but a surge in deaths and a shortage of space has restricted more recent notices to a plain red folder, labelled in black ink: "In memory of."

Ms. Bird, the president of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), pauses on a photo of a man in his late 50s, smiling, with short salt-and-pepper hair and a trim goatee. "Tex" is written neatly under his photo, "November 3, 2016," to the side.

"They called him Tex because he was from Texas," Ms. Bird said. "He died right outside my door."

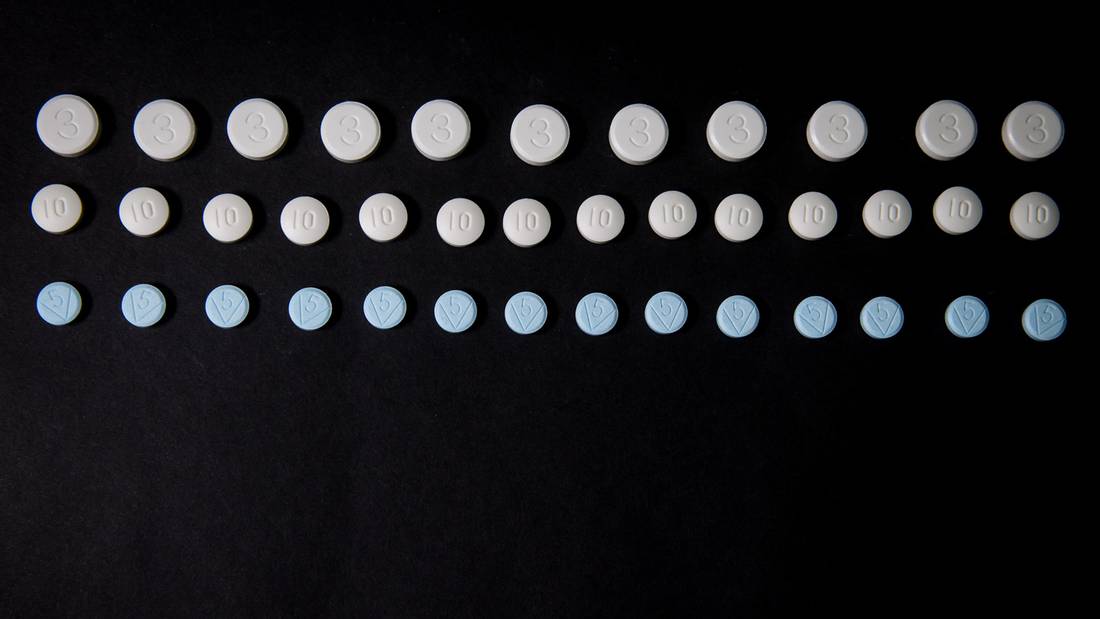

Tex was among 922 people to die of an illicit drug overdose in B.C. last year, the province's worst year on record for such deaths. The figure is nearly five times the average of years since 2000 – but the scope of B.C.'s overdose crisis is measured not just in fatalities.

April 14 marks one year since B.C. declared a public-health emergency. Since that day, 919 people have died and roughly 25,000 overdoses have been reversed – by physicians in hospitals, by peers in back alleys. Social-housing providers have become front-line responders, attending to thousands of overdoses in Metro Vancouver alone. Hard-hit communities, such as Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, have lost friends faster than they can be counted.

Overdoses

For every person who died of an overdose last year, B.C. recorded at least 27 overdoses that were reversed. This estimate is based on overdoses reported at emergency departments, overdose prevention sites and major social-housing providers, and it is likely a gross underestimate due to the number of overdoses that are treated within the community and never recorded.

While the figure is staggering, health officials say it speaks to the efficacy of initiatives implemented so far: Under a provincial harm-reduction program, nearly 30,000 naloxone kits – used to reverse opioid overdoses – were distributed free-of-charge to drug users in the past year. Overdose prevention sites, which the B.C. government opened in December, sidestepping federal rules that guide official supervised injection sites, have reversed more than 2,000 overdoses since December.

"People say to me, 'You want us to spend millions of dollars and it doesn't seem like anything you've done has done any good,'" said Patricia Daly, chief medical health officer for Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH). "We think it would have been worse if we hadn't done these things.'"

VCH, which logged 98 overdose deaths in December and January, could have seen up to 20 more deaths had it not been for such interventions, according to preliminary analysis from epidemiologists with the health authority.

Indoor deaths

About 90 per cent of all illicit drug overdose deaths in B.C. are happening indoors, in private residences, shelters and single-room occupancy hotels. PHS Community Services Society, which operates 19 buildings, intervened in 2,026 overdoses last year – around 500 more than Insite, Vancouver's public supervised injection site. Atira Women's Resource Society intervened in about 625 over the same period; RainCity Housing, 120.

Andy Bond, senior director of housing for PHS, said the appropriate response to the evolution of opioid-based drugs is to "get resources into community hands via training, supports and funding." PHS runs four of the B.C.-sanctioned overdose prevention sites, including one at a residential building in Victoria, and hopes to expand further.

Meanwhile, Atira has converted a suite in each of around 18 of its buildings into "shared using rooms," CEO Janice Abbott said.

Looking forward

At an update on the overdose crisis this week, Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson spoke of the "incredible frustration and anger" he felt over the rising death toll. It's estimated that 110 people have died of drug overdoses in Vancouver this year – already more than half of last year's total of 215.

"Despite many people's best efforts on the ground, it's not slowing down," Mr. Robertson said.

But while solutions have been put forth, many roadblocks remain. For example: Heroin-assisted treatment, championed by some addictions physicians, has in recent months garnered the support of all levels of government.

Mr. Robertson has asked that $8-million of the federal government's $10-million allocation for B.C.'s overdose response go to scaling up supervised injectable opioid-assisted treatment (siOAT) such as prescription heroin. The B.C. Centre on Substance Use is drafting guidelines on what various models might look like.

However, Provincial Health Officer Perry Kendall noted that siOAT – an intensive, last-resort treatment – is not universally accepted even among addictions physicians. And it is costly: Each patient on the program at Vancouver's Crosstown Clinic costs about $25,000 a year. The one-time infusion of $10-million, Dr. Kendall said, is better spent on training, building treatment networks or on one-time health-related capital expenditures such as supervised consumption sites.

At the same meeting, both Dr. Kendall and Dr. Daly called – as they have before – for the government to consider decriminalization.

"I work with the public-safety component of this on the drug task force appointed by Premier Christy Clark and they would acknowledge that we are unlikely to arrest our way out of this," Dr. Kendall said.

"And although I think there is a lot of opportunity for treatment, I think we are unlikely to treat our way out of this. So I think it is time to have a discussion to look at alternate regimes that might offer Canada better options than we currently have."

On Thursday, the Mayors' Task Force on the Opioid Crisis, which convenes mayors of 13 Canadian cities, issued its first set of recommendations, which included a new pan Canadian standard for collecting, reporting and accessing data on opioid overdoses and deaths. At present, only two of the task-force cities – Vancouver and Surrey – have access to monthly overdose data.

Remembering

Memorial walls erected to remember the dead are covered in names within hours. Most recently, one sprang up on Vancouver's East Hastings Street, near an overdose prevention site and street market frequented by those who use drugs. Another sits along a stretch known as the "Surrey Strip. And there is the one in the VANDU office.

There, John Puff surveys the death notices, scanning for familiar faces. In Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, full names can be elusive, which complicates the grieving process. Many don't know how to identify the friends they have known for years, or where to find out what happened to them.

"Around here you don't get a lot of names: 'This is John,' or 'This is Sue,'" Mr. Puff says. "It's mostly faces. You put up their pictures and I know them all."

Advocates have called for the BC Coroners Service to release the names of those who have died of overdoses – something it has occasionally, though seemingly arbitrarily, done. The service says it is reviewing its practice to ensure it is in compliance with the Coroners Act and will no longer be releasing names of the dead until that review is complete.

Ms. Bird, VANDU's president, is thinking about creating profiles for members: a page with a photo, vital statistics, a few lines.

"There are so many people that you'll go, 'Oh, I know that person but I don't remember their name,'" she said. "It would be nice if they could turn around and look at something and say, 'Oh yeah, this is who that was, and where they came from.' It's sad when you've known someone for so long and you can't even say where they were from, what their name was, or when their birthday was."

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL:

…