Even though human activity has done harm to the environment, new research has found the traditional lifestyle of First Nations people who inhabited a stretch of coastline in British Columbia is a boon for forest ecology thousands of years later.

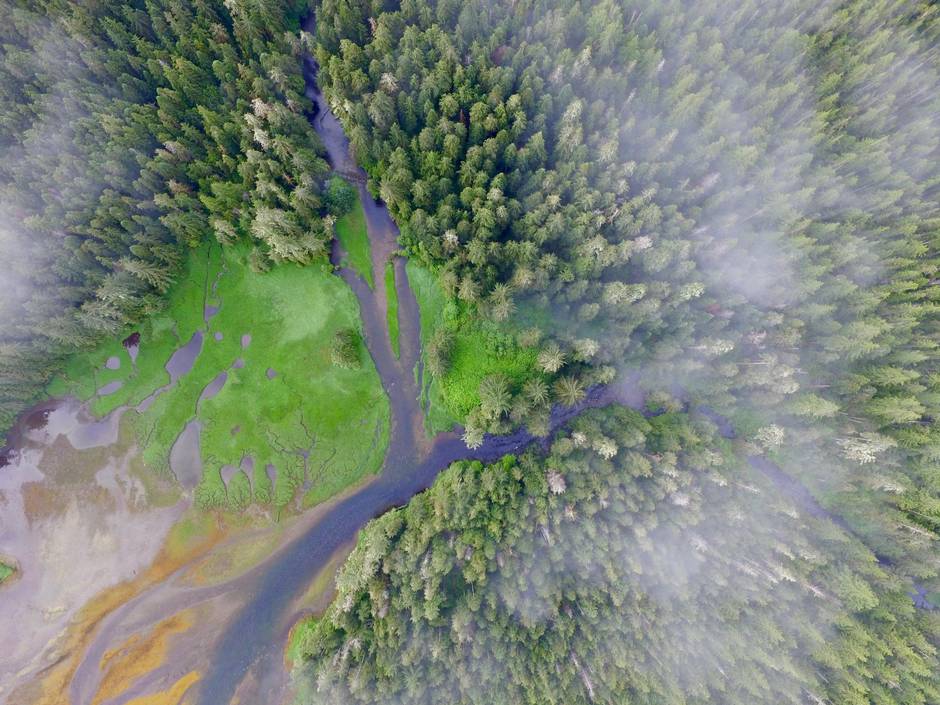

The research team surveyed Calvert and Hecate Islands, which are off the central coast of B.C., collecting soil samples and studying the health of the western red cedar trees that grow there.

They found the trees are healthier in areas that have evidence of past civilizations, and they give credit to large middens – accumulations of organic materials containing things like shells, fish bones and charcoal – that people left behind. These, along with ancient fires, have enriched the soil with nutrients like calcium and phosphorous.

“What we were looking at was how these forests were functioning, and the fact there’s more biomass,” said Andrew Trant, lead researcher of the study and assistant professor at the University of Waterloo’s School of Environment, Resources and Sustainability. “The trees are healthier when they’re growing in close proximity to these sites.”

The study, which was conducted from a scientific research station called the Hakai Institute, was published in Nature Communications.

Researchers found the trees are faster-growing, with greater girth, greenness and fuller crowns, than those in control sites away from traditional habitation zones. The soil in the control areas has lower levels of calcium and phosphorus and is more acidic, Dr. Trant said.

First Nations people lived in the area for more than 13,000 years, until about 200 years ago, he said, “longer than any other known human occupation anywhere in North America.”

The contents of shell middens depended on diet, to a large extent. Given the geographic location, it consisted of what could be gleaned from the sea, such as clams.

“We can think of the midden material as being this nutrient subsidy that people were bringing onto land,” he said.

“You can think of fire as a catalyst because it helped to transform the nutrients coming from the midden material into something the trees and plants can use. Fire is well documented to increase the pH of the soil.”

The layering of shells and other materials created more effective drainage systems, too, he added.

Shells were used to create level platforms for villages found all over the coastal region in B.C., said Dana Lepofsky, a Simon Fraser University archeologist who has worked in the area. “Shells are a fabulous, malleable material. It’s just the perfect construction fill available and it adds to the sediment.”

Nutrient-packed soil in certain locations is part of indigenous peoples’ lasting legacy, Dr. Lepofsky said.

“If you look in the very soils that are throughout the Amazon, for example, this dark earth is the result of people living, cultivating and managing this landscape over the millennia.”

Dr. Trant emphasized these are culturally rich archeological sites and that similar examples are found all over the world. “We do think that this isn’t isolated just to this part of the central coast of British Columbia.”

The research is particularly comforting at a time when people in the scientific community are fixated on humanity’s negative effects on the environment, he said.

“There’s a lot of discussion right now about … how humans are leaving this mark on the planet,” he said.

“It’s really negative, but this is a nice example of the opposite – it’s refreshing.”