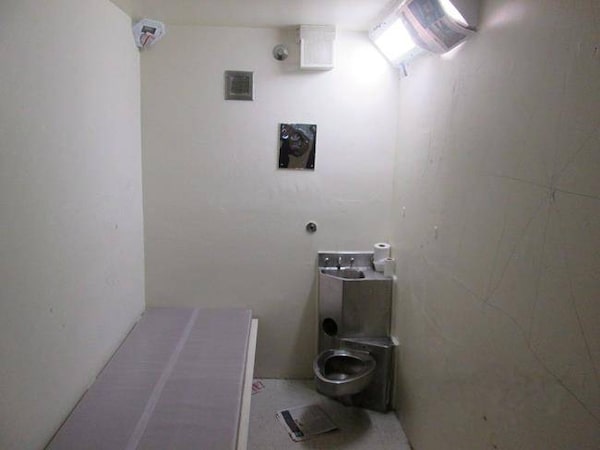

A solitary confinement cell is shown in a handout photo from the Office of the Correctional Investigator.

An inmate at a federal prison says he could feel his mental state "deteriorating" after nearly a month in solitary confinement.

James Lee Busch, who is a prisoner at British Columbia's Mission Institution, testified on Tuesday in a case challenging the use of solitary confinement in Canada. He is one of about half a dozen inmates expected to take part in the B.C. Supreme Court trial, a rare opportunity to hear directly from prisoners who have experienced such treatment.

Mr. Busch said he has been in administrative segregation eight times – three instances while he was serving a sentence for aggravated sexual assault and five since he pleaded guilty to second-degree murder in 2010.

Solitary confinement: How four people's stories have changed Canada's hearts, minds and laws

Mr. Busch, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia in his early teens, testified by video, although most of his evidence was entered through an affidavit.

"I know that I have committed crimes and that I deserve to be punished for them. But, I am still part of this Canadian community and I do not believe that any Canadian deserves to suffer the consequences of segregation," he wrote in the affidavit.

He said he has spent nearly all of his adult life behind bars, or on probation or parole, and still struggles with his experiences in solitary.

His longest stay in isolation was 66 days in 2009, when he was at Saskatchewan Penitentiary. He said he was placed in solitary in that instance for two reasons: He passed a guard a note inviting her to call him once he was released; and he cursed at a psychologist who wanted to prescribe him psychotropic medication.

A spokesperson for Correctional Service Canada confirmed "it is not within the professional scope of psychologists within CSC to prescribe medications. Only psychiatrists and physicians within CSC have prescribing authority." In his affidavit, Mr. Busch refers alternately to a "psychologist" and a "psychiatrist."

Mr. Busch said he had negative experiences with such medication in the past.

Mr. Busch testified that he was born in Edmonton in 1977 and is a member of the Cold Lake First Nations. He said his mother battled addiction and died by suicide in 1992. The next year, he said, he was sexually assaulted.

He said he was first placed in administrative segregation for seven days in 2008 because guards were concerned about his aggressiveness toward other inmates. He spent 10 days in segregation in June, 2009, because guards believed his behaviour was becoming threatening, he said.

The 66-day stretch began that October and Mr. Busch said he would spend 23 hours a day in a small cell. He said he had been taking high-school equivalency courses and had progressed from having a Grade 5 education to nearly graduating. But he could not attend classes while he was in solitary and, ultimately, lost his motivation, he said.

Mr. Busch said he almost immediately felt depressed in solitary.

"The suicidal feelings began almost as soon as the door of the segregation cell closed behind me," he said.

Mr. Busch said his segregation was reviewed four times during the 66 days and it was not made clear how he was a threat to the institution.

During his second review, on the 27th day, he said he asked to be returned to the general population because he knew his mental state was deteriorating.

His third review was on Day 54 and Mr. Busch said he "felt like dying." He said he later agreed to take the psychotropic medication and was released from segregation in December, 2009. He said he believes solitary confinement was used to "coerce" him into taking the medication and he was extremely anxious and touchy when he was returned to the general population.

Mr. Busch was released from prison in March, 2010, but was arrested again two months later and charged in the killing of Sandra Marie Ramsay in Saskatoon.

His longest stretch in solitary since he returned to prison was in November, 2010, when he was placed in segregation for 25 days for fighting another inmate.

The BC Civil Liberties Association and the John Howard Society of Canada sued the federal government in January, 2015, over the use of solitary. The trial began last week in Vancouver.

The Globe and Mail has reported extensively on the prevalence and effects of solitary confinement, beginning with a 2014 investigation into the death by suicide of Edward Snowshoe after 162 days in a solitary cell.

A federal government lawyer used his cross-examination to question Mr. Busch on why he was sent to solitary. In the first instance, Mr. Busch denied being aggressive to other inmates. He also denied wrongdoing in the second instance.

Mr. Busch acknowledged he was placed in solitary in October, 2011 – the sixth instance – because he had fashioned a weapon out of metal. He said he had been feeling paranoid and concerned someone was out to get him.