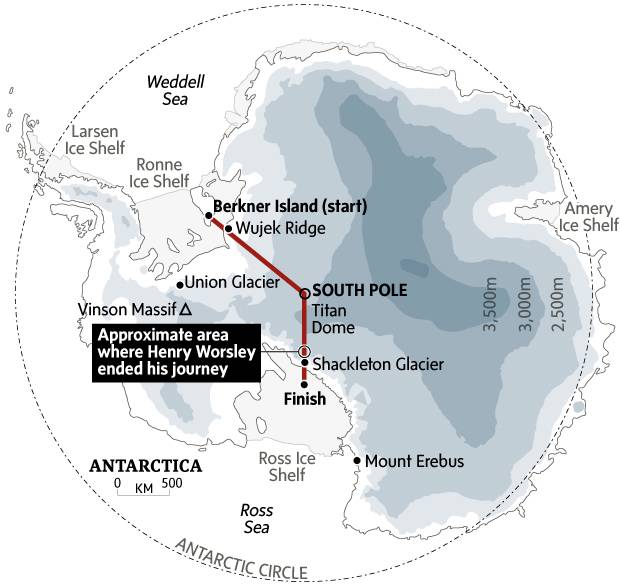

Henry Wosley’s route across Antarctica.

TRISH McALASTER / THE GLOBE AND MAIL/HENRY WORSLEY / SWNS.COM

Henry Worsley, a newly retired British lieutenant colonel, reached the South Pole for the third time on Jan. 2. It was –42 C.

Mr. Worsley, raising money for wounded British soldiers, had travelled, alone and unassisted, for 51 days. He was on skis, pulling a heavy sled with food and supplies, but there was more to go: He was roughly two-thirds through what was to be the first solo and unassisted mission across Antarctica.

At the pole, in a short audio recording, Mr. Worsley said there had been many darker days and, choking back tears, thanked his wife Joanna, his 21-year-old son Max and his 19-year-old daughter Alicia.

"They have been with me every step," he said. "I owe them everything."

On Sunday, Mr. Worsley died of organ failure in a clinic in southern Chile, after he had been airlifted from Antarctica. On Friday, Mr. Worsley had realized he could not forge onwards. He had covered almost 1,500 kilometres – and was about 200 from the finish. In his final broadcast, his voice was laboured. His face had gone gaunt, his cheeks were ravaged, his body exhausted. But he spoke of convalescence.

"The first thing I'll do," he said, "is get a hot cup of tea."

The 55-year-old was inspired since boyhood by British explorers who became stars in their successes and failures in the early 20th century. Mr. Worsley was especially entranced by the men who sought the South Pole, his hero Ernest Shackleton in particular.

There was a familial strand connecting Mr. Worsley and Mr. Shackleton, who in 1909 nearly was the first to reach the pole and, more famously, later led a failed expedition that morphed into an incredible rescue story. On that expedition, Frank Worsley, a New Zealander and distant relative of Henry Worsley, was captain of Mr. Shackleton's ship, the Endurance, and an essential leader of the rescue.

In 2008-09 and 2011-12, Mr. Worsley led trips to the South Pole, the first retracing Mr. Shackleton's steps a century earlier.

Mr. Worsley's return to Antarctica two months ago was a coming home. His first day was easy, over forgiving terrain. It was sunny, –7 C and calm. There were familiar sounds, the swish of skis, and also the resounding silence. "It's just the best place on earth right now," reported Mr. Worsley on Nov. 14 as he set camp.

He soon was enveloped by "white darkness" – the whiteouts he experienced so often during the trip. With no visibility, he travelled essentially blind.

On Day 20, conditions were awful. "The usual," he said: driving snow, cold, high winds, whiteout. "It seemed crazy to set off this morning but I have to press on."

In the white swamp, he was moving downhill – but didn't realize it was steep. His sled suddenly overtook him – "rather alarming, in its suddenness." It knocked him over, dragged him, and then the sled flipped. But the incident didn't cause any harm.

The journey was a slog. He often battled sastrugi – hardened wind-sculpted waves of snow that slowed him – and later the snow became something like wet sand.

Henry Worsley stands with his patron, Prince William, in October before attempting his Antarctica crossing.

John Stillwell/AP Photo

Three days before Christmas, he wondered, "How to put into words the feeling of despair?"

A century ago, such journeys to the South Pole or to the summit of Mount Everest were firsts, explorations. Today, firsts come in variations, though they remain incredible tests. In 1997, Norwegian Borge Ousland was the first to make a solo and unassisted crossing of Antarctica – but used a kite to pull his sled. In 2012, Briton Felicity Aston was the first woman to cross alone – but supplies were dropped along the way.

Mr. Worsley would have been the first to go solo, on his own power, with no supply caches. But he didn't make it. Before it ended, he strove forward, 14- and 16-hour days, sleeping little.

On his previous mission, his son Max had inscribed on his skis the maxim that success is the result of repeated small efforts.

Midway on this journey, Mr. Worsley spoke about spending most of his time not thinking, focused only on each slide of the ski. But in the moments his mind wandered, his thoughts ranged: what his next energy bar would be, those who came before, Mr. Shackleton, and most often, family.

"I often visualize my wife and children," he said, "walking beside me, urging me on."

Henry Worsley on day 62 of his crossing.

Shackletonsolo.org

From the daily audio journal of Henry Worsley

Day 2, Nov. 14, 2015

My first full day in the saddle. I'm pleased with the distance covered. The sledge is actually pretty difficult to pull over even the smallest bump at the moment and the last 30 minutes uphill today was not popular. No wind at all today and a comfortable -13 degrees under sun and broken cloud. Music certainly helped today. Lots of Bowie, Johnny Cash and Meatloaf.

Day 9, Nov. 21

It was on this day [100 years ago] the Endurance succumbed to the vice-like grip of the Weddell Sea and disappeared from view. What an awful feeling that must have been for the crew to witness that and to know that now their survival was in doubt. I am hunkered down in my tent while outside a 30-mile-an-hour wind batted it from all sides. Substantial drifts have built up by the side of the tent and it's extremely noisy.

Day 19, Dec. 1

Half day today. Toughest yet in terms of weather visibility and surface. The highlight of the day was a four-hour storm that blew with such ferocity – 30-35-mile-an-hour winds, -31 wind chill, driven snow. The light was so flat, that on two occasions immediately after stopping, I fell straight over, such is the disorientating effect it has on your senses.

Day 36, Dec. 18

I rose early today … and was on the trail at 4:45 this morning. The sun was dominant all day … and I faced a light easterly breeze. Even that took the wind chill down to -31-degrees Celsius. The 15-hour day was full of all sorts of surfaces. Lots of sastrugi causing varying degrees of delay. I should reach 7,000 feet tomorrow. In sum, a long but productive day. Not one I'm likely to repeat often before reaching the pole unless I desperately have to.

Day 43, Christmas Day

I'm lying in my sleeping bag, cigar in one hand, phone in the other and a rather grubby [unintelligible] cup of Royal Brackla whisky by my side. Perfect way to celebrate Christmas if you can't be with your family. I opened numerous small lightweight – mostly edible – presents from my wife, Joanna, and daughter, Alicia, lovingly and carefully prepared for me.

Day 51, Jan. 2

Location, 90 degrees South. In all my planning and preparation for this journey, I estimated the journey to the pole to take 50 days, so I'm very content to have done it in 51. I owe so much to all of you for your support in getting me this far. I cannot emphasize too strongly just how much it has urged me on in the darker days, of which there have been many. But those I have to thank most are Joanna, Max and Alicia. They have been with me every step of the way. Each with a warm hand in the small of my back lifting me when I'm down, strengthening me when I am weak and filling me when I am empty. I owe them everything.

Day 66, Jan. 17

It's been a punishing day. An 80-per cent whiteout persisted all day. The cruelty though is the very soft snow. It was hellish, all day. Weaker now, of course, it was the last thing I needed. It saps what little energy I have left straight out of my now very skinny legs into the cold air.

Day 69, Jan. 20

It's been a very unproductive day unfortunately, on the realization that I simply don't have time to reach the ice shelf for the intended pickup. My sights are now set on the blue ice. At least then I will have reached part of the destination.

Final day

Today, I have to inform you … my journey is at an end. I have run out of time, physical endurance and a simple sheer inability to slide one ski in front on the other to travel the distance required to reach my goal.

Trekking through a harsh environment such as Antarctica takes an enormous toll on the body

Antarctica can be extraordinarily strenuous on the human body.

During 71 days of single-handedly lugging 150 kilograms of supplies over almost 1,500 kilometres of terrain and dealing with fierce environmental conditions, Henry Worsley confronted dangers with enough power to whittle away at strength, morale and the immune system.

Hannah McKeand is a pre-eminent polar explorer who set a record in 2006 for being the quickest to make it to the South Pole on skis.

"It's a monotonous task getting across Antarctica, physically and emotionally," Ms. McKeand said. "Everything about it resists your movement across it – your being within it."

Dr. Greg Wells, a University of Toronto professor of kinesiology whose research includes studying how the human body performs under extreme stress, says the window for error in a place such as Antarctica is slight, making the risks involved during such a journey great.

Simply sweating can induce a pang of fear.

This is because excessive perspiration can have potentially lethal consequences. To avoid this, Dr. Wells said there needs to be a moderate workload.

"As soon as you start sweating, you lose heat very fast because water evaporates from your skin, which can put you into a state of hypothermia within minutes," he said.

The intense dry-cold climate can lead to dehydration, which can cause a plethora of different effects. Dizziness, fatigue and cognitive impairments are common symptoms.

"It's extremely easy to get dehydrated in the cold because the air gets so dry, it pulls moisture out of your body," Dr. Wells said.

"You lose an enormous amount of fluid just by breathing."

The metabolic system works harder in colder temperatures for the body to stay warm, which requires more nutrition.

"I've heard of people eating straight butter wrapped in bacon in order to get the calories they need to keep going," Dr. Wells said.

"When you're not fuelling yourself appropriately and don't have enough nutrition, that can cause weakness, compromise the immune system and open yourself up to sickness."

It's not uncommon for someone to develop a cold, or disease, after experiencing high stress.

"When your body is under tremendous stress, the body spends its energy on fuelling movement and reconstructing proteins to rebuild muscle tissue and sometimes the immune system gets compromised, leading it to not fight off disease like it's normally able to if you're rested and well fed."

UV rays beaming down on the snow 24/7 and reflecting on exposed skin can also cause harsh blisters.

Low oxygen due to an elevation of 9,000 feet near the South Pole poses the risk of altitude sickness, too.

"For the first half of the trip, Worsley would have been constantly climbing from a relatively low level near the sea," Dr. Wells said.

Being entirely self-sufficient is also a test of mettle.

The best way to cope to is to keep busy, according to Ms. McKeand.

"You're constantly focused on the

basics of life. It reminds you of what it's like to be a human animal."

– Julien Gignac