This article is part of The Unremembered, a Globe and Mail investigation into soldiers and veterans who died by suicide after deployment during the Afghanistan mission.

After his military discharge, all Joe Rustenburg wanted to do was leave reminders of his torn army life behind. The Edmonton-based infantry soldier did two tours in Afghanistan. On his first deployment in early 2006, he went to the fractured nation hopeful and wanting to make a difference. On his second tour, he just wanted revenge for all the friends he lost in the sweltering Afghan desert.

He was showing signs of post-traumatic stress disorder before he went back to the war zone in 2008, but he said it was easy to bluff past mental-health questionnaires and assure military doctors that he was fine. Once he returned home, his health crumbled quickly.

Struggling with nightmares and flashbacks, the retired corporal only slept about three hours a night. To calm his nerves, he smoked two-and-a-half packs of cigarettes a day and got black-out drunk at times. The army had taught the young husband how to kill, but it hadn't prepared him for how killing would make him feel. His moral compass had shifted.

"Before my first tour, I was a fairly positive person," the Ontario-raised army veteran said. "And then from my experiences and the trauma that it caused, it made me become dark, cold and uncaring."

Mr. Rustenburg during a tour in Afghanistan.

Photo courtesy Joseph Rustenburg

In June, 2009, nine months after his second tour, Mr. Rustenburg attempted to end his life. He took all the sleeping pills and medication he could find, drove to a farmer's field and laid down. He had just been diagnosed with PTSD.

"I didn't know what was going on. I felt the pain was so intense and I felt that my wife would benefit with me not being there, because she wouldn't suffer any more," he recalled thinking. "In reality, that's not the case, but when you're in that situation, that's what you feel is right."

When Mr. Rustenburg awoke a few hours later, he was relieved to be alive. Deeply alarmed by his suicide attempt, his wife, Melanie, began fighting to get him intensive treatment. He said it took nearly a year before the military sent him to Homewood Health Centre, a 300-bed mental health and addiction facility in Guelph, Ont. At Homewood, specialists reduced his medication and taught him how to cope with his panic attacks and other PTSD symptoms.

He felt so good after his four-month stay that he wanted to return to his infantry group. Instead, he was sent to the Joint Personnel Support Unit, created during the Afghanistan war to help ill and injured soldiers heal. Chronically under-resourced and understaffed, the support unit has struggled to aid many vulnerable soldiers. Mr. Rustenburg said his time in the JPSU sent him into a spiral.

"They totally undid all of the positive work that had been done" at Homewood, he asserted. "By the time the JPSU was done with me, I was in crisis and I was released."

Medically released from the military in January, 2011, Mr. Rustenburg and his wife moved to La Ronge, Sask., where her parents lived. He needed to get away from Edmonton, and the small northern Saskatchewan town seemed like the perfect spot – remote, quiet and nowhere near a military base. "To me, it was a safe place. It felt like a sanctuary," he said.

But the fractured veteran was also far from treatment, and not seeing a psychologist or taking medication. Eventually, his mental health worsened and he withdrew into isolation. His wife begged him to get help.

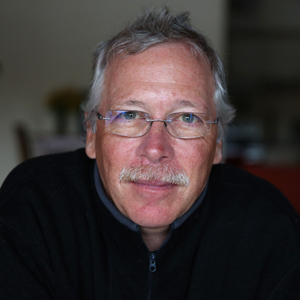

Mr. Rustenburg and his wife Melanie. He credits her with pushing him to get help.

David Stobbe for The Globe and Mail

In 2013, Mr. Rustenburg began seeing a therapist again, driving two hours to Prince Albert for appointments. In August, a black labrador service dog named Vixen came to live with him. She was a gift from the Wounded Warriors Weekend group, and helped him tremendously by alleviating panic attacks and nudging him back to reality when he's having a flashback.

But he didn't bring Vixen to our interview at the Tim Hortons in Warman, about 25 kilometres north of Saskatoon. The couple moved to the growing bedroom community in February, 2015, to be in a less-isolating location and closer to Mr. Rustenburg's medical appointments in Saskatoon. He attends therapy twice a week, meeting with a psychologist and undergoing neurofeedback sessions to retrain his brain. He was recently diagnosed with a traumatic-brain injury, the result of a bomb blast in Afghanistan, his doctor suspects. He was approved for medical marijuana in June, and uses it to help him sleep.

Long shut off from others, Mr. Rustenburg struggles to express emotion (the inflections in his voice don't change as we talk), but he is making progress. He and wife go out on dates now, to the movies, restaurants and hockey games. He's taking a Brazilian jiu jitsu class, and he's able to sit in a busy coffee shop and talk with a reporter he's never met – unthinkable a few years ago.

"The best thing you can do is reach out, get help and talk about it," he said of dealing with PTSD. "Once you understand what's going on with you, you can get better and you can manage it."

And when you fall, he added: "Keep getting up. That's the biggest thing."

At 34, Mr. Rustenburg doesn't know if he will be well enough to work again. He hopes so, but there is a lot more healing to do. He receives long-term disability payments from Veterans Affairs, which he feels guilty about at times. "But I have to remember I have no career prospects," he said. The Afghanistan war forever changed his life.

He still has dark moments, especially when the Prairie weather turns cold and bleak. His loving wife keeps his thoughts of suicide at bay, he said. She is studying to become a police officer and has stood by Mr. Rustenburg through his tours and their aftermath.

"She kept me alive when I gave up on life and didn't want to keep going," he said when we talked on the phone another time. "I am immensely thankful that she didn't leave. A big part of my success is Melanie and [spouses] don't get a lot of credit for that."

She is by his side through the hour-long phone conversation. "I don't need credit," I can hear her whisper. She is Mr. Rustenburg's rock.

More from The Unremembered project