Lorraine Leniuk is off to a family funeral.

And she couldn't be happier about it.

The burial is set to take place on Thursday, Aug. 24, at the British military cemetery just outside the town of Loos-en-Gohelle, France. The graveyard is next to the new Canadian monument to the Battle of Hill 70, which was unveiled in April and which will be formally opened to the public this coming Tuesday, two days before the funeral of Private Reginald Joseph Winfield Johnston.

Mrs. Leniuk's great-uncle Reg will finally be officially laid to rest after spending a full century as one of the "missing" during this nearly forgotten but pivotal battle in the history of Canada.

He was all of 22 years old, a homesteader from Fairford, Man., who left the farm to sign up at age 20. He fought at Hill 70 and fell on Aug. 15 or 16, 1917, either the first or second day of the 11-day fight to take this strategic rise of land. He was but one of nearly 2000 Canadian soldiers to die here, more than half of whom still have no known graves.

More than nine decades passed before the remains of Pte. Johnston were recovered. Bones were uncovered at a nearby construction site along with a small button from the Canadian Expeditionary Force's 16th Battalion. That button narrowed the possibilities down considerably, as 39 members of the battalion remained "missing in action."

The Defence Department's casualty identification program sent forensic anthropologist Sarah Lockyer to France to examine the remains. She later contacted potential relatives requesting saliva swabs to see if a DNA match could be found.

"I thought, after 100 years how is that possible?" Mrs. Leniuk says. "But with science today, I figured 'Why not give it a whirl?'"

Mrs. Leniuk turned out to be a match. Soon, other family members were contacted and arrangements made for them to go to France for a proper family funeral. Mrs. Leniuk, 80, is coming with her husband, Eugene Leniuk, from Petersfield, Man.; Ethel Cottrel, also 80, will come from Lac du Bonnet, Man., with her daughter Caroline Armstrong from Kenora, Ont.; and Dale Johnston, 78, from Le Pas, Man., will be accompanied by his daughter Carol Johnston of Red Lake, Ont.

"I expect it will be a very humbling experience," Mrs. Leniuk says. "How things come in a circle. His picture was on my grandmother's wall and now I'll be carrying that picture to France."

"It will bring peace to the family," Ms Johnston says. "I like to think my great grandparents and my grandparents are all smiling down to know he's been located and given a proper burial."

Another lost-but-found soldier, Sergeant Harold Wilfred Shaughnessy of St. Stephen, N.B., will also be buried that day at the Loos cemetery. He was unmarried and would have turned 33 in November, 1917. He died on the first day of the same fight that took the life of Pte. Johnston.

Sgt. Shaughnessy had been a stenographer with the Canadian Pacific Railway prior to enlisting in Montreal in the summer of 1915.

He joined the 13 th Canadian Infantry Battalion formed by the Royal Highland Regiment. His remains were found a year ago during munitions-clearing by workers in advance of a construction project.

Ms. Lockyer, the forensic anthropologist, was able to use a pipe, razor, toothbrush and signet ring with the soldier's initials to identify the remains and then track down relatives near Boston.

Jack Kennedy, a great nephew of Sgt. Shaughnessy, is a retired school teacher from Kingston, Mass. For years, Mr. Kennedy used a three-page, single-spaced typed letter that he found in his grandmother's home as a way of getting his students to understand the First World War and its effect on those who fought.

Over the years, as the students studied the letter and learned about Sgt. Shaughnessy's whereabouts during the war, "He was coming more and more to life" for us.

On the day Mr. Kennedy was contacted by Canadian defence officials about the discovery, he walked into class and excitedly told the students, "They found Harold!"

The Battle of Hill 70 lingered in obscurity for 100 years, fairly marked in its moment but then largely forgotten, perhaps because it took place between two more famous fights that retained a strong historical and psychological grip on Canadians: Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele.

Yet, it was at Hill 70 that Canadians forged a most remarkable victory. In earlier battles, neither the British nor the French had been able to dislodge the Germans from this vital coal-supply area. Their failures had resulted in tens of thousands of casualties.

The battle would be the first time the Canadian Corps fell under the command of a Canadian, Lieutenant-General Arthur Currie. Lt.-Gen. Currie's reaction to his very first order – to take the town of Lens – had been to suggest to his British superiors that he had a better idea.

If his troops could take the nearby Hill 70 – so called because it was 70 metres above sea level – then from the hill they could at least keep the Germans holed up in Lens and prevent them from sending reinforcements to their forces under siege elsewhere along the Western Front.

British Command listened and decided to go with Lt.-Gen. Currie's alternative. He mapped out a superb strategy, planned the attack intricately and executed brilliantly. The Canadians took and held the position through 21 German counterattacks – proof of Hill 70's vital strategic importance.

It was an unbelievably horrific fight in a year filled with such bloodshed. A journal kept by Arthur Lapointe, a signaler serving with the 22nd Battalion, described the initial assault in graphic detail: "4:25 a.m. Zero hour! A roll of heavy thunder sounds and the sky is split by great sheets of flame. … I scramble over the parapet and … am one of the first in no man's land. … The noise of the barrage fills our ears; the air pulsates, and the earth rocks beneath our feet. I feel I am in an awful dream. … Now we are crossing ground so torn by our barrage that no soil remains in place. … We reach the enemy's front line, which has been blown to pieces. Dead bodies lie half buried under the fallen parapet and wounded are writhing in convulsions of pain. … A section in the second wave has come up a communications trench and opened fire with a machine-gun on the Germans. … Now they lie in a mass of grey, with blood splashed all around. One lifts a hand to his chest and falls in a dugout entrance. I shall never forget his face, a mask of tortured agony. … The sun is spreading golden rays over all this carnage and destruction, as though mocking at the strange folly of mankind."

The Canadian victory came at a heavy cost. Lt.-Gen. Currie's troops suffered nearly 8,700 casualties in the 11 days of fighting, while German estimates of losses ran between 12,000 and 20,000. A total of 1,877 Canadian soldiers lost their lives here and more than 1,100 of the Canadian soldiers suffered from mustard-gas poisoning.

Six Victoria Crosses were awarded to Canadians who took part in the Battle of Hill 70: Private Michael O'Rourke, Private Harry W. Brown, Sergeant Frederick Hobson, Major Okill M. Learmonth, Sergeant-Major Robert H. Hanna, Corporal Filip Konowal. At Vimy Ridge, the Canadians had won four Victoria Crosses.

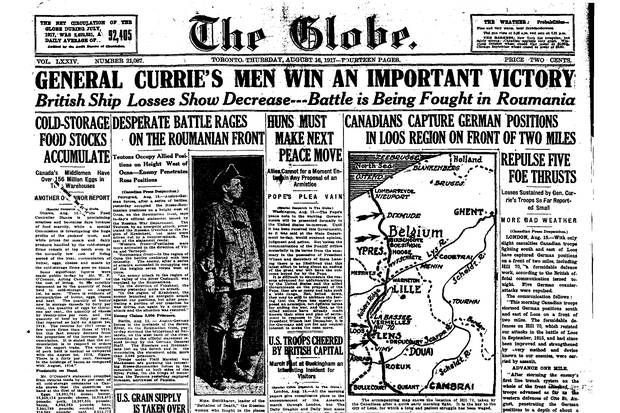

The front page of The Globe and Mail on Thurs. August 16, 1917 showing the Canadian occupation of Hill 70.

The Battle of Hill 70 might have remained lost to all but dedicated military historians had it not been for the work of the Hill 70 Memorial Project, chaired by Colonel Mark Hutchings and a team of three dozen volunteers. ("We pay our own gas," Col. Hutchings says. "We make our own sandwiches.")

Governor-General David Johnston agreed to serve as the charity's patron. With no government funding, the group set out to raise $8.5-million to build the memorial at Loos.

Individual donors contributed $1-million each, multiple corporate donors came forward with funding. Others, including The Globe and Mail, stepped up with contributions in kind.

The project entailed multiple initiatives: a book, Capturing Hill 70: Canada's Forgotten Battle of the First World War; a children's graphic novel on the battle; a bilingual portable museum; a multifaceted educational program for about 3,500 high schools across the country; and, of course, a website (hill70.ca).

The group was able to gain permission from France to build the memorial on eight hectares of parkland given over by the town of Loos-en-Gohelle. The site is not the actual Hill 70 – that is now a suburb of Loos – but parkland alongside the cemetery where Pte. Johnston and Sgt. Shaughnessy will be interred.

The French were so accommodating to the Canadians that an accountant in Lens, a small city nearby, referred them to an old French law that exempted such projects from value-added tax. The French ambassador to Canada, Nicolas Chapuis, took up the cause and the French government agreed to the exemption, saving the group about €425,000 ($629,000) in construction costs.

In April, the Hill 70 Memorial was unveiled as well as a rising walkway with a small Maple Leaf embedded to represent each Canadian who fell in the decisive battle, more than 200 of whom are buried in the nearby cemetery.

Initiatives since then include a musical tribute, Hill 70, composed by Jim Finan, and the Frederick Lee Walkway, which honours the contributions to the Allied cause during the First World War by the Chinese Canadian community and mainland China. In 1917, the British, French and Canadian armies recruited 140,000 Chinese labourers who served as support behind the front lines. Frederick Lee was one of hundreds of Chinese Canadians who enlisted in the army.

The 21-year-old soldier from Kamloops, B.C., died at Hill 70. As well, educational materials on the young soldier and the Chinese contribution will be distributed to the 3,500 high schools that were involved earlier in learning about the significance of the battle.

The Hill 70 Memorial Project has introduced Canadians to a special moment that deserves its place in the coming of age of the country. No such introduction, however, was ever necessary for the families of those soldiers who fell in the battle.

In page after page of messages that came in with contributions to the project – some small, some remarkably generous, all equally welcomed – it is plain that the soldiers were not forgotten, if the battle was. The families of the lost soldiers would never forget:

"My Great Grandfather Charles Reed was killed on 15 August, 1917 in the Battle of Hill 70. His body was never found. He had lied about his age to join the Canadian Army. He was 39. God rest his courageous soul."

"For my grandfather, Private John Fleming – 883632, who was missing in the Battle for Hill 70 but is still in our hearts."

"My uncle Pte. Milfred Steinburg (2nd Batn. Eastern Ontario Regiment) was killed at Hill 70 on August 17, 1917. His body was never found or identified. I will be there on that day in 2017. Thank you for this memorial."

For Dale Johnston, a retired heavy-duty machinery mechanic who will be making his first trip to Europe for his uncle's burial, the photograph of the young soldier in uniform never did fade. So young to die; so very long to be found.

"It's kind of mind-boggling that they could do this after all that time," Mr. Johnston says.

"We knew he was missing for a long, long time," he says of his uncle. "We didn't think he'd ever show up.

"At least now he's going to get a proper funeral."

Editor's note: This article has been corrected to show the number of Chinese labourers recruited to be 140,000, not 140.