Capturing a war crime

Ron Haviv shares that experience with Dr. Anthony Feinstein, a world leader on the psychological effects of war on frontline journalists

In Rudyard Kipling’s book, The Light that Failed, published in 1890, he portrayed a foreign correspondent whose “experiences dated from the birth of the needle-gun … [and who] always opened his conversation with the news that there would be trouble in the Balkans in the spring.”

One hundred years later, American photojournalist Ron Haviv arrived in the Balkans to find that not much had changed. Long-standing ethnic tensions were simmering and Yugoslavia was about to disintegrate into civil war. Haviv’s first stop was Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia, soon to secede. From there he moved on to Croatia where he met Zeljko Raznatovic, known as Arkan, a Serb nationalist and career criminal, who led his own paramilitary group, the Serb Volunteer Guard also called Arkan’s Tigers. Haviv was working with another photojournalist at the time, Alexandra Boulat. “Alex was very beautiful and very charming, and we asked [Arkan] if we could take his portrait,” he recalls. “He got his men to put on their masks, they jumped on a tank, he stood in front of the tank and somebody handed him a live tiger [cub] and we took the picture.”

“Arkan loved that picture,” Haviv recalled, and it gained him entrée to the Tigers. By now the Yugoslav dominoes were toppling and when Haviv next met Arkan it was in Bosnia at a town called Bijeljina. He reminded Arkan that he’d taken the tiger photograph: “And [I] asked for his permission to go with him and his unit as they, in his words, cleansed the town of Muslim fundamentalists.” Arkan agreed, a decision that would have far reaching consequences for him and Haviv, too.

Haviv recalls what happened next. “As we moved through the streets of the town there were already civilian bodies on the sidewalk, on the stairs of homes. … I’m not sure if they were Muslim or Serbian. Eventually we reached … a mosque and they went into [it] and took down the Islamic flag and put up a Serbian flag. They posed for a picture. … I heard a commotion in another room … they had taken a young man [prisoner] and they were telling me he was a terrorist. … They said he’s Kosovar, he’s Albanian, so for them that guaranteed he was a terrorist and as they were interrogating him I was taking photographs. … I heard more shouting, so I went outside and across the street a middle-aged woman and man had been brought out and everyone was shouting. The woman was shouting. The soldiers were shouting. And then … multiple shots rang out … the man went down. … At the same time they were all yelling at me, ‘No photographs, no photographs!’ ”

Haviv had seen summary executions before in Croatia and had been prevented from photographing them by the perpetrators. He was determined not to let this happen again. “I had made a promise to myself that if I was ever to be in that situation again I would have to walk out with the evidence of what was going on.” The events unfolding in front of him in Biljeljina now tested his resolve.

“A truck had crashed in the middle of the street,” he remembered. “I used that to shield their view of me. I took a couple of frames of the woman trying to save her husband and then I walked back to the soldiers. … They shot her, and then another woman was brought out and they shot her as well.”

Haviv later discovered the three people killed were related – a husband, his wife and his sister-in-law.

By now he was acutely aware of his own vulnerability in a rapidly unfolding situation of extreme lawlessness. But he was also driven by a passion to bear witness – his motivation heightened by an inability to stop the killings. “I realized that even though I had a few frames of the victims, I needed verifiable proof that this was being done by these guys. … I just wanted a photograph of the paramilitaries and the bodies of the people as they lay dying in the same frame and [for this] I had to go into the middle of the street. … I lifted up my camera and from my left came this young guy who is now a DJ in Belgrade, wearing sunglasses, cigarette in hand and he brought his boot back and I took a couple of frames…”

Their suspicions aroused, the militia forbade Haviv from leaving until Arkan returned. “At this point, I’m obviously incredibly nervous because they are going to tell him I was there during the executions, so I managed to hide the film I already shot in my car.

As Haviv is waiting, he hears a crash. A young man has been thrown out a window above. He lands at Haviv’s feet. It is the Albanian prisoner Haviv had recently photographed at the mosque. He survives the fall. “They start kicking him” he recalls. “They douse him with water. They say they are baptizing him. Meanwhile I’m photographing. They drag him back into the house. Moments later Arkan arrives. One of the soldiers comes up to him and whispers something in his ear and Arkan comes over and says, ‘Look, I need to see your film. … Give me your film and I’ll process it and whatever I like I’ll give back to you, and whatever I don’t, I’ll keep.”

Haviv realizes he has lost the film that is in his camera. But Arkan is not aware of the other film hidden in the car. “So, we get into this conversation,” Haviv tells me, “about how good the labs are in Belgrade and how it’s better for Arkan to process the film and bring it back to me and so [on], and in the end I give him the film. I get back in the car. I drive straight to the airport and I send the photographs.”

When the photograph of DJ Max kicking the dead civilian is published a week later, Haviv is in Sarajevo. Arkan is enraged. He is on record telling a Swedish journalist he looked forward to the day when he could drink Haviv’s blood.

Over two decades have passed since Haviv took the photograph that so powerfully captured the depravity of the Balkan civil wars. He is a quiet, intense man, and while time has not lessened his passion for his work, it has allowed him to reflect on how the photograph affected him and others. On a personal level, he could not ignore Arkan’s threat. Serbian colleagues warned him that he was now on a wanted list. While he continued to photograph the war in Bosnia, he was always on guard, vigilant, mindful that he had to stay one step ahead of the warlord.

Excessive caution, however, is not compatible with conflict photography. There are simply too many variables to control in war zones. One day, Haviv and photojournalist Luc Delahaye unwittingly drove past a secret Serbian military installation, and were promptly arrested and accused of being spies. Taken to a farmhouse they were interrogated, beaten and subjected to mock executions. Haviv thought it was all over for him, more so when he recognized a guard as one of Arkan’s Tigers who had been present during the ethnic cleansing of Bijeljina. Surely the man would remember him, too? But in one of those bizarre quirks of fate, the guard had an identical twin and it was the twin who had been complicit in the killings.

After three days of mental and psychological torture, and following the intervention of the American, Russian and French governments, the photojournalists were released. “It was like a scene out of a movie,” Haviv recollected. “[On a] foggy day we were handed over to a guy from the KGB in a long trenchcoat at the end of a bridge.”

Undeterred, Haviv went back to covering the Bosnian war, but not before first returning home to apologize to his girlfriend.

“Why apologize?” I asked.

“For putting her through all of this.”

“And what about you?” I queried. “What was going through your mind [during your captivity]?”

Haviv paused before answering. “It [was] no longer in my control. I did make a very conscious effort to try and find some balance between continuing to defend the idea that I’m not a spy, that I’m there as a journalist, but at the same time giving them the satisfaction that I was terrified and so on. … I had to find a way [to] lessen the blows.”

Listening to Haviv describe how he was able to modulate his emotions under these fraught and perilous circumstances reminded me of similar accounts I have heard from other frontline journalists. Reactions like these should not be misconstrued as an absence of fear. Haviv was quite open on this point: “I was scared, there was no question of that.” Rather, it refers to an innate ability, part of a hard-wired adaptability, that allows journalists like Haviv not necessarily to master fear, but rather to navigate an uncertain passage through it in search of safety. It is a recurrent theme that runs through the narratives of that select group of journalists whose temperament has allowed them to spend decades in war zones. In extremis, their thoughts retain a clarity that keeps behaviour rational and focused on that most capricious of outcomes, survival.

Arkan cast a large shadow over the life of Ron Haviv. Even when back home in the United States, Haviv feared him, particularly when Arkan was indicted in 1997 by the international war crimes tribunal in The Hague, with Haviv’s photographs as supporting evidence. “I was very nervous,” Haviv divulged, “because it’s not hard to find me … and for him to pick up a phone and call some guy and say shoot [him].”

Arkan never made it into court. In 2000 he was assassinated in the lobby of the InterContinental Hotel in Belgrade.

The power of Haviv’s photograph to sway decisions at The Hague highlights the broader legacy of his work. His Balkan war images were also used as evidence in the trials of Slobodan Milosevic and Radovan Karadzic. And he could never have predicted how an image of a nonchalant, brutal kick would galvanize a nation.

“The Bosnians adopted the photograph as a call to arms,” Haviv told me. “I’ve seen posters in Libya, Saudi Arabia and Turkey and other places with that picture saying ‘Come Fight for Your Bosnian Brothers’. I turned on the TV one day and saw a protest about the Bosnian war … hundreds of women in black chadors holding up the photograph. … Artists have done interpretations of the photograph, famous cartoonists have done comic strips about it.”

Twenty years after the photograph was published, Bosnians still respond to Haviv in a way that amazes him. “I’m so happy to meet you … I appreciate everything you did. And then they start crying,” Haviv told me. “It’s actually very uncomfortable because Bosnia is a country suffering still from PTSD … if you scratch a little bit, you’re at war. Even for the people born after the war, because of the stories. Which is one of the problems in that area where everything is fed by oral histories.”

If Haviv is made uncomfortable by the emotions of others stirred by his photographs, what then of his own feelings? “These are very difficult moments to relive, photograph and look at,” he confided. “Even though I’m highly convinced that there was nothing I could have done to save [them], it’s incredibly difficult to watch people dying in front of you especially in that way, unarmed, doing nothing wrong, no reason for it to happen.”

Haviv fell silent for a moment before going on. “It’s something that’s part of my memory and my being.”

Anthony Feinstein is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto and on staff at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. He is the author of Journalists Under Fire: The Psychological Hazards of Covering War.

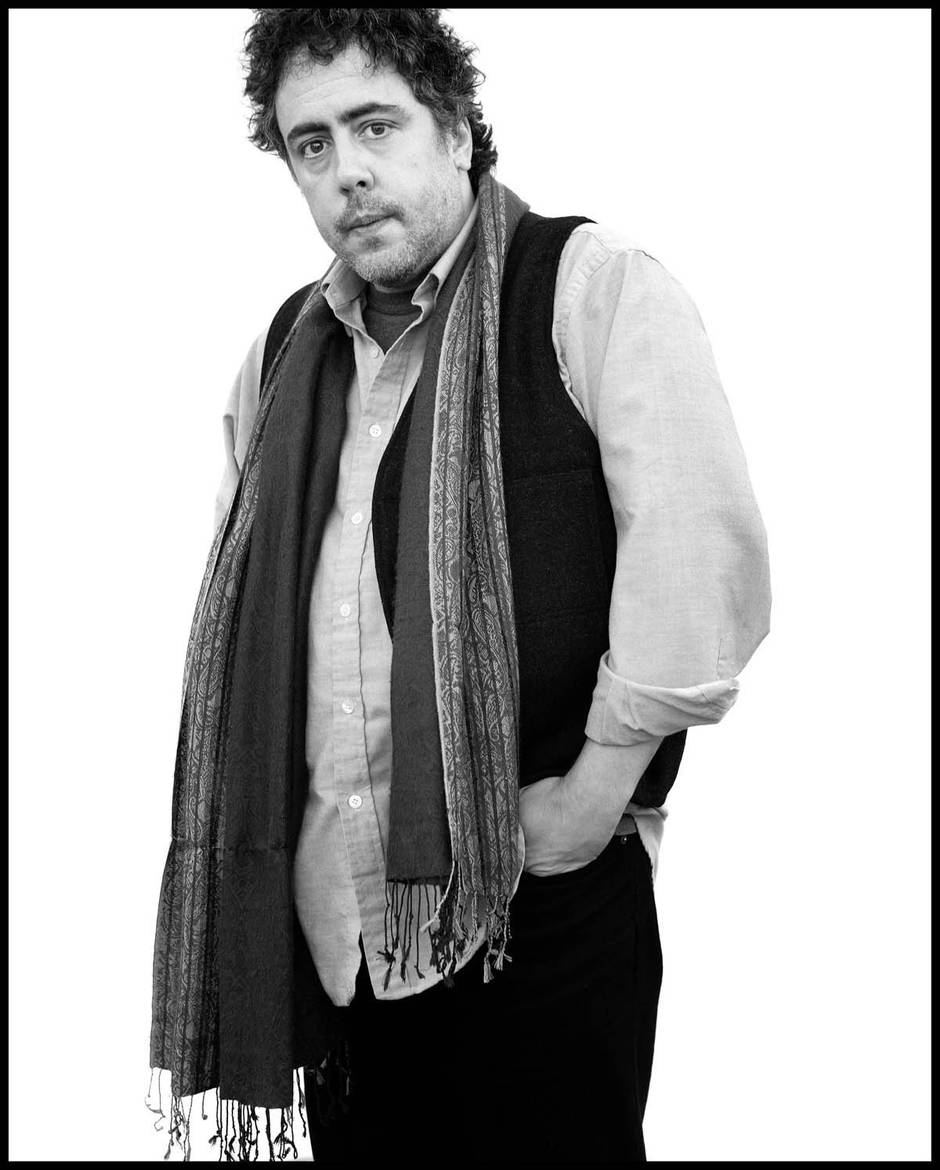

Ron Haviv portfolio

Ron Haviv is an award-winning photojournalist and conflict photographer who as documented international

and civilian conflicts around the world since the Cold War.

Ron Haviv is an award-winning photojournalist and conflict photographer who as documented international

and civilian conflicts around the world since the Cold War.

His work on Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, Russia and the Balkan concentrates not only on the direct effects of conflict but also upon the humanitarian consequences which are longer term and continue long after the gunfire has ceased. His books Blood and Honey: A Balkan War Journal, and Afghanistan: On the Road to Kabul and the magazines he has published in including Fortune, The New York Times Magazine, TIME, Vanity Fair Paris, Match and Stern attest to the quality of his work in complex and fast-changing situations where intuition and self-preservation are as important as camera skills. His book Haiti: January 12, 2010 addresses the effects of the earthquake upon society. His awards include World Press Photo, Picture of the Year, Overseas Press Club and the Leica Medal of Excellence.

Appreciating the need for a different kind of photo-collective to support and market the images of photographers he co-founded VII in 2001.

Follow Ron Haviv on Instagram and Twitter