Sergeant Raynald Côté

Marie-Claude Deschêsnes has a dream where soldiers such as her partner, retired Sergeant Raynald Côté, return from war to an intensive treatment and debriefing centre in the countryside. Those diagnosed with mental-health issues would stay with their families, sorting it all out with professionals and peers until they're on a path to recovery and everyone has the tools to cope.

"I know, I'm living in a dream world," Ms. Deschêsnes said. "The cost of something like that would be enormous. But that's how I see a system that might work."

Mr. Côté wasn't one of those veterans who spent years sinking into illness in isolation with his post-traumatic stress disorder. Athletic and charming, he wasn't afraid to ask for help, and took part in therapy and mental-health research projects and every program he could find. Still, depression and paranoia set in and he died at the home he built in the countryside near Quebec City on Dec. 27, 2015.

The new suicide-prevention strategy doesn't contain Ms. Deschênes's pastoral treatment centre, but promises to do better. Trying to increase awareness in the ranks and among families is vital and an emphasis on social media and peer intervention "may help the ones who are in their basements," she said.

Better preparation – for missions, for postdeployment, for civilian life – should also help, but still may not reach the necessary level of intensity for those who need it most, she said. "There are some really good points, but this is becoming a plague out there," she said. "An hour a week with a therapist isn't going to do it for a lot of people."

Les Perreaux

Sergeant Claude Emond

Maintaining a sense of purpose is the one thing Sylvie Duchesne believes might have saved her husband. She doesn't see that on the list of action items in Ottawa's suicide-prevention strategy.

Retired Sergeant Claude Emond shot himself at home in Quebec City on Sept. 2, 2014, nine months after being medically released from the military suffering from twin afflictions: post-traumatic stress disorder and 11 herniated discs in his back.

Steady deterioration in both conditions left Mr. Emond paranoid and unable to walk more than a few steps. "After years of running all over the world, of being part of a team, he was sent home to collect a cheque while his wife was at work and kids were at school," Ms. Duchesne said. "That killed him more than anything."

Sylvie Duchesne, widow of retired army Sgt. Claude Emond, outside her home in Quebec City on Oct. 5, 2017.

Dario Ayala / The Globe and Mail

Mr. Emond, 48, spent his tour of duty in Afghanistan maintaining vital refrigeration systems on bases and outposts. That technical knowledge could have been put to good use, Ms. Duchesne maintains.

But still she sees much positive in the strategy. Good intentions count, she said, and measures to improve preparations for families – particularly those faced with the medical release of their soldier-loved ones – should help, she said. "I often found myself outside looking in. It wasn't until it was too late that I had the full picture of what was going on," she said. "Deeper involvement would have helped us both."

Les Perreaux

Corporal Sean McClintock

Tom McClintock will applaud every new government initiative that takes aim at preventing further suicides in the Canadian military. "Anything is better than nothing," said the father of retired Corporal Sean McClintock, who took his own life in February, 2016.

But for all the programs that were available to his son when he retired from the Canadian Forces, Mr. McClintock said it was something far less regimented that provided Sean with any true sense of comfort. That relief came from the Southern Ontario-based Niagara Military Vehicle Association, a group of veterans who share a love for restoring old military vehicles and are there for one another emotionally. Together, they did more for Sean McClintock than any doctor or psychiatrist, insisted the father.

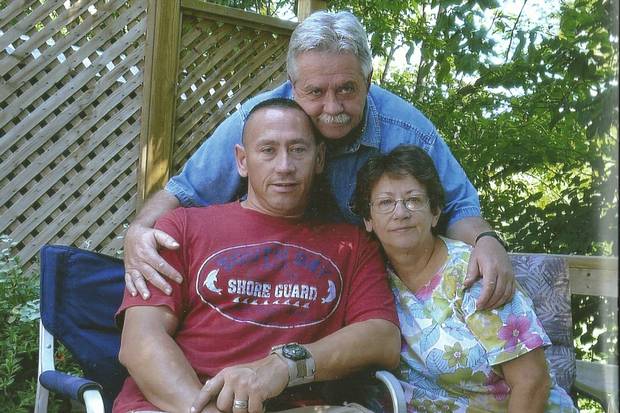

Corporal Sean McClintock with his mother, Pam, in Alberta.

Tom McClintock

"He would have been worse off without those other veterans," said Mr. McClintock, who added the military has to be more vigilant in anticipating the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental-health issues.

"They did the debriefing after Afghanistan and that's when they determined Sean was suffering from PTSD. At that point, I knew he was suffering from PTSD from his tours in the Balkans, long before he ever went to Afghanistan. It wasn't detected early enough," Mr. McClintock noted. "It was just piling on."

Allan Maki

Corporal Tony Reed

Micheline Reed placed flowers at her son's grave at Beechwood Cemetery in Ottawa earlier this week. Another mother was by her side, honouring another son lost to suicide.

Both were soldiers. One was a reservist who had just turned 21, while Corporal Tony Reed, a 43-year-old father of two, had served in Afghanistan and was grappling with post-traumatic stress, financial troubles and a relationship breakdown when he ended his life on Dec. 7, 2012. He had attempted suicide twice before.

Ms. Reed and her husband, Phillip, felt helpless as they watched their son struggle to get sufficient help from the military's overburdened medical system at CFB Petawawa. They wanted to be part of his care.

Corporal Tony Reed with his parents, Micheline and Phillip.

"I felt pretty much totally out of the loop during my son's period of suicidal ideation and all the things that were going on at work," Mr. Reed said.

The joint suicide-prevention strategy from the military and Veterans Affairs is supposed to bring families into the care plan and teach them how to help someone who is in a mental-health crisis. The military also plans to provide additional support to soldiers who attempt to end their lives.

"The soldiers need to be treated with a little bit more respect when they're going through episodes, and not just dismissed with medication," Ms. Reed said. "They need counselling, and I think the family needs to be involved in that as well."

Renata D'Aliesio

Captain Patrick Rushowick

On Thursday, Bonnie Rushowick received news the Canadian Armed Forces and Veterans Affairs had unveiled their comprehensive suicide-prevention strategy. Come Tuesday, she and her husband Geoff will receive the Memorial Cross in Yorkton, Sask., for having lost their son, Captain Patrick Rushowick, to suicide in June, 2013.

Being awarded the medal signals a significant change, considering how the military first refused to honour those soldiers who killed themselves. Ms. Rushowick hopes the prevention measures prove meaningful in dealing with matters of "mental wellness."

"Everybody needs to have some sort of a mandatory tune-up," Ms. Rushowick said. "For God's sake, the amount of money we put in to maintaining the infrastructure, the weapons. We make sure our technicians are up to date. But what do we do for the [soldiers]? They do need that support but it has to be a variety. One size does not fit all."

Ms. Rushowick is keen to see a system that doesn't just offer a series of health services, it incorporates front-line players – chaplains, sergeants, captains – and uses their input to contact soldiers instead of waiting for them to make the first move.

"In my job with civil services we're dealing with youth suicide, young First Nations kids. Girls as young as 10 are killing themselves because they don't see hope. And that's what our veterans are doing … we have to reach out and grab them."

Allan Maki