The group was getting restless. It was nearing the end of an all-day meeting and, despite hours around the table, they were still at loggerheads.

The purpose of the September Health Canada meeting was for government, health groups and the food industry to sit together and narrow down a list of potential designs for labels that government will soon make mandatory for food and drinks. Any packaged food high in sugar, salt or saturated fat will have to be labelled as such.

The government and health groups were in favour of a simple design, modelled after a "stop" or "yield" sign. They brought up expert after expert who testified to the benefits of a clear, easy-to-understand symbol.

But the food and drink industry reps were not having it. They termed it the "big, scary stop sign" and accused government of trying to "scare" Canadians. At the same time, they argued the designs were patronizing – overly simplistic, and not allowing for nuance or context.

By late afternoon, several of those in the room were looking visibly tired, and irritated.

"Frankly, I think taking an approach like this is just not giving Canadians the respect they deserve," said Lewis Retik, a lawyer hired by the food industry to attend the meeting. "They're not idiots."

As Mr. Retik continued to speak, one man who had been listening with growing consternation – Ian Culbert, the head of the Canadian Public Health Association – had heard enough. Video of the meeting shows Mr. Culbert shaking his head and grabbing the microphone to interject. Soon, both men were talking over one another with raised voices.

Everyone else just sat glum-faced, watching.

'Another 30 years before we get this chance'

Health Canada's announcement last year that it would implement these mandatory labels drew enthusiastic responses from health organizations. More than one-fifth of Canadians are obese, and obesity and diet-related chronic illness are estimated to cost the country up to $7.1-billion each year. Meanwhile, cardiovascular diseases (heart disease and stroke) are among the leading causes of death in the country. Front-of-package labels, officials say, could help curb this.

The new labels are meant to clearly indicate to consumers when a serving contains more than 15 per cent of the daily value of salt, sugar or saturated fat. Once implemented, the program would make Canada a leader in food labelling – and the only country in North America mandating these types of health-related "warning" labels on food.

But, as that September meeting illustrated, the plan has its critics. Dozens of pages of e-mails, letters and briefing notes exchanged between government and the food industry, and obtained by The Globe and Mail, make clear the uproar Health Canada has sparked. Those documents, together with video of the September meeting and interviews with attendees, reveal the fierce debate surrounding the labelling project – and the fierce lobbying against it by the food industry.

Since the Health Canada announcement, groups such as the Canadian Beverage Association (whose clients include Coca-Cola and PepsiCo Inc.), and Food & Consumer Products of Canada (who hired Mr. Retik, and whose members include Campbell, General Mills and Dole) have put significant pressure on Ottawa to re-evaluate.

They've submitted for consideration their own proposals – designs the health groups say are confusing, and defeat the purpose of labels altogether. Health Canada has met with many of the groups affected by the labelling plan – including industry and health groups. As promised last year by the government, all meetings and materials related to those meetings have been made public.

Now, with a draft regulation from Health Canada expected in the coming months, health organizations are worried. The department has yet to make public a detailed timeline. But over the past few months, it has narrowed its list down to just a few potential designs.

Despite positive signals so far, the health groups fear that the industry's influence could still lead to a softened approach. For health groups, the election of the Liberal government in Ottawa (which came with a slew of new healthy-eating policy announcements), presents to them a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. They're worried the opportunity could go to waste.

"If this isn't done," said Manuel Arango, director of health policy at the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, "it could be another 30 years before we get this kind of a chance."

RECOMMENDED READING

'The Chilean approach'

The information customers get from food packages now is mostly limited to the "Nutrition Facts" table on the back – a mandatory system put in place in 2007. But there's often little conformity to how this information is presented.

In the cereal aisle at a grocery store this week, three brands of granola, all made by the same company, were displayed side-by-side. The nutrition facts table on the Vector granola listed 290 calories, 14 grams of fat and 10 grams of sugar. That was based on a serving size of half of a cup of cereal with no milk. The All-Bran granola right next to it had only 200 calories, and 2.5 grams of fat. But that information was based on a different serving size – two-thirds of a cup. And unlike Vector, there was no information for the addition of milk. The Special K Nourish granola next to that had information based on yet another serving size – three-quarters of a cup.

Further complicating matters are the many labels producers voluntarily placed on those products – advertising everything from protein levels to "vitamins and minerals" to the absence of artificial colouring.

This confusion is why Health Canada and health groups are so eager to have in place simpler, more intuitive labels.

"While existing nutrition-labelling tools are very useful to many consumers," Health Canada wrote in its proposal, "some consumers find the information provided too complex to understand and use."

At the September meeting, it was David Hammond who responded to Mr. Retik's "idiot" comment.

Dr. Hammond is a professor of public health at the University of Waterloo and, throughout his career, has researched the effectiveness of warning labels on everything from food products to cigarette boxes to alcoholic-beverage containers. More than once that day, he referred to his experience on tobacco warnings – a comparison that earned him the ire of the food groups across from him.

Dr. Hammond pulled the mic toward him. "I would agree, Canadians are not idiots," he said. "But neither are they nutritionists and dietitians."

In his work, Dr. Hammond has studied consumers' understanding of dietary guidelines – how well they are able to interpret labels in order to evaluate the healthfulness of different foods. What he's found is that the majority of Canadians aren't able to do either.

In general, he told the meeting attendees, only 24 per cent of people are able to correctly identify their recommended daily calorie intake.

The other experts around the table, including professors from the University of Toronto, University of Alberta and a representative from the Pan American Health Organization, attested to the same.

They emphasized that the lower the socioeconomic status of a consumer – a group especially vulnerable to obesity – the less likely they are to be able to navigate the information on current food labels.

In other words, those who need the information the most are least equipped to get it.

"I think making this information easier for people to understand is not treating them as idiots," Dr. Hammond continued. "It's treating them as people who are trying to make positive changes."

The approach the experts advocated at the September meeting – and that Health Canada seems keen on adopting – is based on Chile's system launched last year. With one of the highest obesity rates in the world, Chile passed a law requiring a black "stop sign" label for any food high in calories, saturated fat, refined sugar or sodium. A product deemed high in all four must carry four stop signs.

After the Chilean system was put in place, a survey showed more than 92 per cent of respondents said that the labels influenced their decisions. And significantly, the change has driven companies to reformulate food products to avoid the warning labels.

This last point is a promising one for Health Canada. Throughout this process, Health Canada officials and health organizations have emphasized their hopes that this could be the case in Canada, too.

RECOMMENDED READING

'Health Canada has lost its way on the obesity issue'

Nine days after the September meeting in Ottawa, Pierre Sabourin, an assistant deputy minister at Health Canada, sent a follow-up letter to all of those who had attended.

In the letter, he thanked the attendees for their perspectives and invited further submissions for new designs. "Please ensure that the symbol fits within the design principles that we agreed upon at the meeting," he wrote.

The responses were scathing.

"In the attached letter, you claim that we agreed to design principles," Christopher Kyte, then-president of Food Processors of Canada wrote (including the italics). "The meeting didn't agree to anything. In fact, that meeting was an excellent demonstration that Health Canada has lost its way on the obesity issue."

(In an interview with The Globe, the FPC's new president, Denise Allen, said the group does not believe there is sufficient evidence that labels can change behaviour.)

The Canadian Beverage Association wrote to express its "deep concerns."

In a statement to The Globe, the CBA said that it hopes Health Canada will "investigate the numerous models used globally and to adopt a model similar to those of Canada's major trading partners."

The Dairy Farmers of Canada wrote in its letter that they would support the front-of-package labelling proposal – but only if "nutritious" dairy products were exempted from the rules.

Food & Consumer Products Canada also sent a note to Health Canada to express its displeasure.

In an interview, FCPC senior vice-president of public and regulatory affairs Joslyn Higginson said that the group supports the principle behind the labelling initiative, but doesn't believe there's enough evidence to justify the Chilean approach. "We just don't think that stop signs or warning signs belong on food," Ms. Higginson said.

She also emphasized the economic impact. In addition to Health Canada, the industry has also put pressure on other departments, such as Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, whose mandate is to support the food industry. "It seems a bit contradictory that the government will be putting warning signs on food at the very time they're trying to grow investments in the agri-food sector," she said.

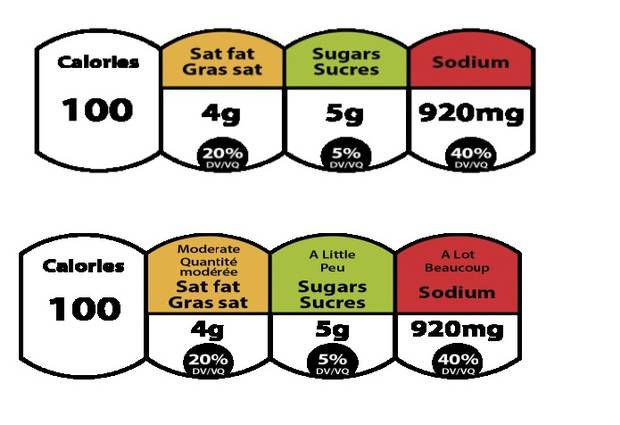

Instead, the FCPC proposed a modified version of a design used in the United States. That design would be colour-coded (red, yellow or green), and display much more information, including the calorie count, and specific amount of each nutrient (grams or milligrams of sugar, sodium or saturated fat).

The nutrition label proposed by the FCPC

HEALTH CANADA

But the design, Dr. Hammond said, is simply too confusing.

That "traffic light" system, he said, is cluttered and leaves too much up for interpretation. Under such a system, a package of potato chips might have a red light for sodium but green lights for saturated fat and sugar. Some consumers might interpret two green lights out of three as healthy.

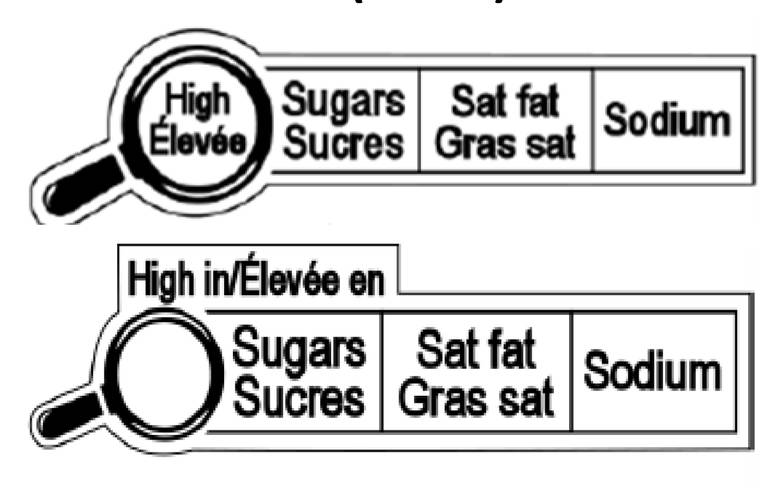

The Retail Council of Canada, which represents the major grocers, also proposed its own design, with a magnifying glass meant to refer customers to the Nutrition Facts table at the back of the box. The RCC's concern with the "stop" or "yield" symbols proposed by Health Canada, it said at the meeting, was that they looked "like a chemical warning."

Still, some companies wanted to distance themselves from the industry groups altogether.

A representative from Nestlé Canada wrote to Health Canada immediately after the September meeting. "I just wanted to say I'm a bit worried about how our industry views have been presented today, and I'm a little bit embarrassed," wrote Fiona Wallace, the company's director of regulatory and scientific affairs. "… A few of us are feeling very frustrated."

Just two months after the September meeting and all of the backlash surrounding it, Health Canada hosted yet another meeting earlier this week, where government officials revealed that it has further narrowed down its list of possible designs.

The "yield" sign has been turned upside-down and made into a triangle – but remains one of the government's favoured options. The "stop" sign has turned into red circles. And the magnifying-glass options remain on the table, too.

Notably absent from the list were the most cluttered and confusing of the food industry's designs. Health organizations are taking this as a positive sign.

Afterward, Mr. Arango from the Heart and Stroke Foundation, said his concerns about industry lobbying have been somewhat alleviated – but only by a little.

"I know how this works," he said. "And the food and beverage industry will not stop."

Health Canada, in response, said the department will continue to take into account all the groups' views. But it emphasized that its priority is health.

"This is a public-health crisis, and a lot of this is very significantly related to diet," said Karen McIntyre, a director-general at Health Canada. "Everything we can do to turn that around is the direction we're taking."

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL ON FOOD

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-goldfish-tgam-thumbnails/07-18-2017/t_1500401442933_name_Untitled_design__3_.jpg)