Read ahead: What is on the table • The Negotiators • The Bosses

The renegotiation of the North American free-trade agreement kicks off Wednesday at the Marriott Wardman Park hotel in Washington. At stake is an enormous amount of business – $1.1-trillion (U.S.) last year alone.

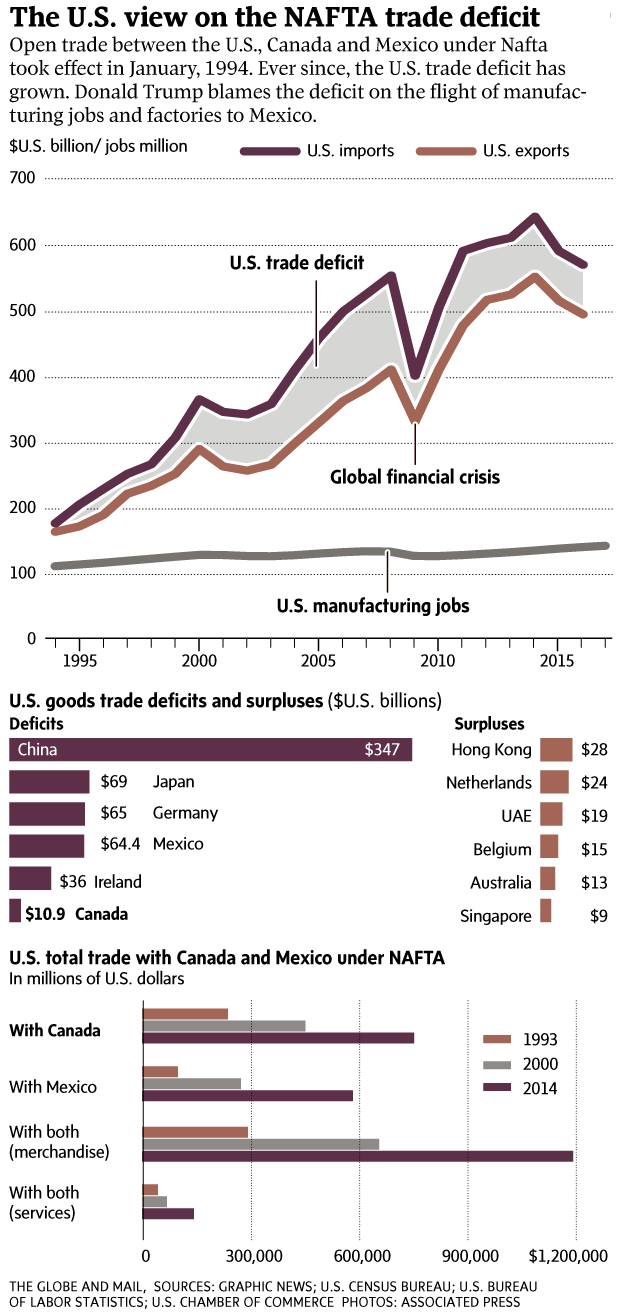

U.S. President Donald Trump triggered the talks, arguing NAFTA has moved money and jobs, particularly in the manufacturing sector, out of the United States.

Mr. Trump's goal is to tilt the playing field in the deal toward his country. A wide-ranging list of negotiating objectives released last month by U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer includes such goals as scrapping the dispute-resolution panels established in NAFTA's Chapter 19, which have ruled in Canada's favour on the long-running softwood-lumber dispute; tightening restrictions on manufactured goods that can be sold within the NAFTA zone without tariffs, including adding a possible U.S. content requirement; and slashing the U.S. trade deficit, which could entail cutting imports from Mexico.

Canada and Mexico will largely be playing defence: The prime imperative for NAFTA's junior partners is to not lose any market access.

"Mexico wants to maintain an agreement that builds a stronger North America; we do not feel the agreement has been unfair," said Luz Maria de la Mora, a former high-ranking trade official in the Mexican government who worked on the original NAFTA negotiations. "The question is: How are we going to get to common ground when there are very different views? It makes life much more difficult as we're not speaking the same language."

A major part of the Canadian and Mexican strategies will be to divert the talks away from Mr. Trump's protectionist impulses and into a discussion about how to update the agreement without adding any barriers to trade. All three sides broadly agree on some elements: Expanding the deal to cover the digital economy; bringing Mexico into the pact's energy provisions, which currently apply only to the United States and Canada; and strengthening labour and anti-corruption standards.

There will be some back-and-forth on the details – how far to go on new environmental regulations, for instance – but the renegotiated deal is certain to include movement on the areas the three countries agree to in principle. It helps that much of this was already written into the Trans-Pacific Partnership and Canada's trade deal with the European Union, meaning a lot of the policy could be quickly copied and pasted into NAFTA.

Canada and Mexico will be hoping such changes are enough to sate Mr. Trump's appetite for a "win."

Dunniela Kaufman, a Washington-based trade lawyer who specializes in U.S.-Canadian business, says this approach could work, particularly as Mr. Trump's stalled agenda has left him desperate for something he can claim as a victory to his supporters.

"The way Trump is behaving, it's The Art of the Deal: You ask for the world and then you pull back," she said in an interview. "He could ask for [a gutting of] Chapter 19, not get it, but settle for some easier stuff, then go back to his base and say, 'Hey look, I renegotiated NAFTA and it's a win.'"

What will be on the table?

The tough stuff

Trade balance and the open market

The top goal on Mr. Lighthizer's list is to "reduce the trade deficit with the NAFTA countries." Mr. Trump believes the U.S. trade deficit – which reached a total of $502-billion last year, including $55.6-billion with Mexico – is a result of jobs moving out of the country. The Trump administration has in the past floated the idea of somehow choking off Mexican imports or discouraging U.S. companies from setting up shop there. Whether the United States will also go after Canada is an open question: It actually posted a modest trade surplus – when both goods and services are considered – with Canada last year. Mexico and Canada can be expected to resist attempts to restrict the current market between the three countries. Mexico's list of negotiating priorities, submitted earlier this month by Economy Secretary Ildefonso Guajardo to the Mexican Senate, lists as its top objective to "maintain preferential access for Mexican goods and services" in the United States and Canada and eliminate "barriers to trade."

Chapter 19

One of the deal's dispute-resolution mechanisms, Chapter 19 allows one country to appeal another country's punitive duties to a binational trade panel. The United States begrudgingly agreed to this provision to seal the original free-trade deal with Canada in 1987 – and has hated it ever since. The trade panels have ruled in Canada's favour on two major softwood-lumber disputes. Mr. Lighthizer wants to "eliminate" them. But Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland is vowing to walk away from the negotiating table rather than give them up. Without the panels, these trade disputes would be resolved in U.S. courts, which Canada does not trust to give it a fair hearing. Mexico is on Canada's side, saying in its negotiating objectives the panels have "proven their effectiveness as an instrument to make regional trade more predictable." Elliot Feldman, a Washington-based trade lawyer who has represented Canadian interests for more than two decades in the softwood dispute, says this dispute-resolution mechanism was Ottawa's top priority in 1987 and for good reason: Canada believes punitive duties are the United States' strongest protectionist weapon. "If there had not been a Chapter 19, there would not have been a free-trade agreement," he said in an interview.

Access to government contracts

Ottawa is taking aim at so-called "Buy American" rules that bar foreign companies from receiving government contracts in the United States: Canada is proposing NAFTA guarantee firms from all three countries equal opportunities to bid on public procurement across the free-trade zone, and governments be barred from giving preferential treatment to their own countries' companies. The U.S. is almost certain to fight this: Mr. Lighthizer's list says Washington wants more opportunities for American firms to bid on public procurement in Canada and Mexico, but to keep the right to bar Canadian and Mexican companies from receiving contracts in the United States. The Mexican priorities list says the country wants "legal certainty" in "procurement procedures" – suggesting it will fight to stop any Buy American policy.

Rules of origin

The United States wants to "strengthen" the rules that govern how much of a particular product must be made in North America to qualify for tariff-free export. This would force manufacturers – particularly in the auto sector – to reduce the amount of materials they source from outside the NAFTA zone, or pay tariffs. The priorities list also suggests the United States will push for the right to add a U.S. content requirement on top of the North American requirement – which would certainly become a flashpoint with Canada and Mexico.

Labour mobility

Canada and Mexico want the renegotiated NAFTA to make it easier for businesspeople to get back and forth across the border. Ottawa also wants rules that would allow some professionals to work in all three countries. It is doubtful the United States will be as enthusiastic about this: Mr. Trump has tried to limit immigration. Still, he has been less hostile toward the sort of highly skilled people Canada and Mexico are describing than toward lower-skilled workers whom he accuses of taking jobs from Americans.

The wild cards

Financial services and telecomm

The United States and Mexico want to make it easier for financial and telecommunications companies to do business across all three countries, such as allowing them to operate without setting up servers in the other two countries. But the details could get complicated: All three countries have different banking, telecomm and data collection rules, and working through them to determine what each party wants to keep – and what they are willing to give up in the name of broader business – could be a long and difficult exercise. Canada weathered the 2008 financial crisis better than its southern neighbour because of tighter controls on the finance industry, and will be reluctant to give any of those up.

Cross-border online shopping

Currently, Canadians must pay duties on cross-border purchases over $20 (Canadian). U.S. consumers enjoy a duty-free threshold (called the "de minimis" amount) of $800 (U.S.) and Mexicans, $300. The United States wants to bring the other two countries' thresholds up to its level. Canada has resisted such a change for fear of an increase in cross-border online shopping competition for Canadian retailers.

Chapter 11

Canada wants to weaken provisions that allow corporations to sue governments for policy decisions they claim hurt their business. These rules, spelled out in NAFTA's Chapter 11, have been used by firms to fight environmental laws. Ms. Freeland said she wants to see NAFTA rewritten "to ensure that governments have an unassailable right to regulate in the public interest." Gutting Chapter 11 could also give governments a freer hand to pass protectionist economic legislation – something the Trump administration is likely to be happy about.

The environment, labour, gender and indigenous people

Canada will push for broader social and environmental protections to be written into the deal. Ms. Freeland said Monday she wants NAFTA to ban any government from weakening environmental laws to bring in more business. Ottawa will also look to have chapters covering women's participation in the work force and Indigenous people written into the deal. What, exactly, the United States and Mexico will agree to is an open question. The U.S. wants to incorporate existing side deals on labour and the environment into the core agreement, which would make them enforceable. But it is doubtful Washington would go so far as to agree to Ms. Freeland's standard blocking countries from loosening environmental laws: The Trump administration is pulling out of the Paris Agreement to slash greenhouse gas emissions and eliminating a host of environmental regulations. Mexico, for its part, has listed the environment, labour and gender in its negotiating objectives – signalling it is willing to play ball – but has not spelled out with much detail what exactly it would agree to on those fronts.

Supply management (maybe.)

Mr. Lighthizer's list does not explicitly call for the abolition of Canada's supply management system, but hints that it might be on the table. The document calls for opening up more opportunities to export U.S. agricultural goods by eliminating "tariff rate quotas" and "price discrimination." Supply management sets production quotas for milk, eggs and poultry for Canadian farmers and adds tariffs of up to 300 per cent on imports from other countries; the idea is to ensure a steady income for domestic farmers and keep out foreign competition. Ottawa could use the system as a bargaining chip in talks. Canada accepted more European cheeses as part of its trade deal with the EU, for example.

Softwood (well, sort of.)

Talks to resolve this long-running dispute have been unfolding separately from the NAFTA renegotiation. But if they do not conclude soon, they could become entangled in the broader discussions. The U.S. lumber industry accuses provincial governments of unfairly subsidizing its Canadian counterpart. Earlier this year, the United States put punitive duties on Canadian lumber imports. The two countries are trying to reach a deal that would remove the duties and impose a quota on the amount of Canadian lumber that can be exported to the United States.

Oil, gas and electricity

When NAFTA was signed, Mexico opted out of the energy chapter because its oil and gas industry was under a government monopoly. But President Enrique Pena Nieto has begun allowing foreign companies to invest in Mexican oil and gas. All three countries have hinted they would like to bring Mexico under the energy chapter to lock in Mr. Pena Nieto's reforms. Such a move could create more opportunities for U.S. and Canadian oil and gas companies while cementing part of the Pena Nieto administration's legacy.

Faster customs procedures

Importers and exporters in all three countries would like less red tape at the borders, and Mexico plans to put this on the table.

Intellectual property

The United States wants stronger intellectual property protections, which could target Canada's generic drug industry and force Ottawa to clamp down on counterfeit merchandise passing through the country en route to the U.S. market.

The Negotiators

While overall NAFTA strategy will be set by politicians on each side, the talks will be handled by a small army of professional negotiators. Each country has a negotiator-in-chief to lead these efforts. All three are old hands who worked on the original NAFTA talks.

John Melle

Mr. Melle has worked in the office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) since 1988, through six presidential administrations. Since 2011, he has been assistant USTR for the Western hemisphere, making him the obvious choice to handle the NAFTA renegotiation.

One former colleague, speaking on condition of anonymity, said Mr. Melle has a no-drama style and does not waste time with the sort of posturing or theatrics, such as blowing up or walking away from talks, that more abrasive negotiators sometimes use. Instead, the source said, Mr. Melle focuses on finding a "path to yes" – trying to identify compromises everyone can agree on – as quickly as possible.

Steve Verheul

Canada's main man at the table has been in the thick of this country's trade policy since the 1980s.

Most recently, he spent seven years as the lead negotiator in Ottawa's talks with the European Union, which produced the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA). The negotiations included allowing more European cheese imports into Canada's protected dairy market and extensive discussions over dispute-resolution mechanisms – two issues that could be sticking points in NAFTA talks.

Mr. Verheul worked from 1989 to 2009 on trade policy for the federal agriculture department, including six years as chief agriculture negotiator. He was involved in NAFTA negotiations and the Uruguay round of talks that led to the World Trade Organization.

According to his federal government CV, Mr. Verheul graduated from the University of Western Ontario in 1984 with a master of arts in political science. A profile by The Hill Times said Mr. Verheul is from Southern Ontario, and is the son of a dairy farm equipment supplier.

Kenneth Smith Ramos

Mr. Smith Ramos's 25-year career is coming full circle: He joined the Mexican government in 1993 as part of the original NAFTA negotiating team.

Subsequently, he held posts at the Ministry of the Economy, the Mexican Federal Competition Commission and the Ministry of Agriculture, where he handled the agricultural components of trade deals and ran operations to promote Mexican agricultural products. Currently, Mr. Smith Ramos runs the NAFTA office at the Mexican embassy in Washington.

Ms. de la Mora, the former Mexican trade official, said Mr. Smith Ramos combines a deep expertise in the technical details of the deal with an easy manner. He is close to Mr. Guajardo, who was also a trade official before getting into politics. During Mr. Smith Ramos's long history in Washington, he has forged ties with his U.S. counterparts, Ms. de la Mora said – and is even friends with Mr. Melle.

"He also has this ability to read people; he's very personable. He's a very mellow guy, he's easygoing, but he's very assertive," she said in a telephone interview from Mexico City, where she runs a business consulting firm.

Despite Mr. Smith Ramos's U.S. education – he went to Georgetown University and Johns Hopkins University – and Anglo-sounding surname, Mr. Guajardo assured reporters in Mexico City last month that Mr. Smith Ramos is "super Mexican."

The Bosses

As Mr. Melle, Mr. Verheul and Mr. Smith Ramos work on the details of the deal, other big players from the governments will be looking over their shoulders.

On the U.S. side will be Mr. Lighthizer, Mr. Trump's USTR and the man with oversight of all trade negotiations. Exactly who holds sway in Mr. Trump's chaotic administration at any given time is often difficult to determine, but over the past seven months, Canadian and Mexican officials have dealt with several other people on the trade file, including Jared Kushner, Wilbur Ross, Steve Bannon, Steve Mnuchin, Gary Cohn and Dina Powell.

Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland is Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's NAFTA point person. Others with substantial roles will be David MacNaughton, the ambassador to the United States, and Kirsten Hillman, the top trade official in the Foreign Affairs Ministry who was recently reassigned as Mr. MacNaughton's deputy.

Mexico's Mr. Guajardo is the main cabinet minister on the file; Juan Carlos Baker is the government's top official for foreign trade, and Salvador Behar is the lead for North America in the economy ministry.

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL