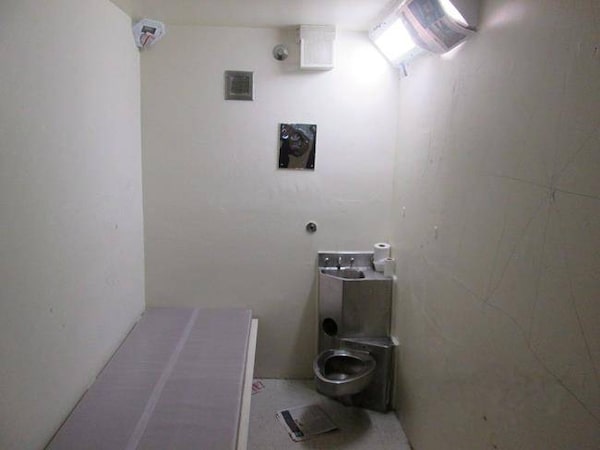

A solitary confinement cell is shown in a handout photo from the Office of the Correctional Investigator.

Federal prisons recorded a significant drop in the number of prisoners held in solitary confinement just one day after the federal prison service implemented new rules barring certain vulnerable groups from isolation cells.

Figures provided to The Globe and Mail show that, as of last Wednesday, the Correctional Service of Canada held 301 inmates in administrative segregation, the internal term for solitary confinement.

That's down from 399 inmates in June and a rough average of 800 inmates three years ago.

Opinion: Solitary confinement is pure torture. I know, I was there

However significant the decreases, some prison-system observers maintain grave concerns about how they were achieved and how easily they could be rolled back.

"The number is going down and that's great," said federal prisons Ombudsman Ivan Zinger, who provided the figure. "But I do have some concerns. In fact, I'm going to put in place a strategy to monitor how these policies are being applied."

The policies in question – commissioner's directives 709 and 843 – underwent major revisions on Aug. 1.

As of last week, several categories of inmate are no longer admissible to segregation cells: those who are seriously mentally ill, imminently suicidal, self-harming, physically disabled, terminally ill or pregnant.

CSC spokeswoman Lori Halfper said the reduction of segregated inmates stems largely from increased efforts over the past two years to divert inmates with mental-health issues "to more therapeutic environments where their needs can be addressed," among other measures. She added that the impact of the new commissioner's directives on the solitary population has yet to be assessed.

Prisoners who do wind up in solitary confinement will be afforded a few new rights, including an allowance of two hours out of their cells, up from one hour previously.

The additional hour outside the cell is widely seen as a positive step, however, its application within Canada's aging prisons could prove tricky.

"It could be very tough to meet that policy," said Gord Robertson, second national vice-president of the Union of Canadian Correctional Officers. "You don't have the space to give everyone two hours of recreation time during a day shift. So that means adding staff on the evening shift, or building infrastructure to accommodate everyone. These are problems we'll have to address on the fly, unfortunately."

Segregated inmates report that, under the old rule, federal prisons had already lacked the recreation space and staff to provide the one hour of recreation at a reasonable hour.

"The men complain regularly that they're being woken up out of a sound sleep when it's pitch black outside to be asked if they want yard time," said Catherine Latimer, executive director of the John Howard Society of Canada. If an inmate declines the early-morning offer of yard time, they generally don't get another chance for 24 hours.

In other cases, officers will ask inmates in segregation to take their recreation time alongside fellow segregated inmates. "And that means two or three or four inmates in the yard at a time," Dr. Zinger said. "If it's safe, that's no issue. Where I get concerned is that if an inmate declines the offer because they feel unsafe spending rec time with others, they will be marked down as declining exercise for the entire day. These are the kinds of operational things we will want to monitor."

Ms. Latimer said barring certain vulnerable groups from segregation is a step in the right direction, but she and most other prisoner-rights advocates would rather see such a measure in legislation rather than policy.

The Liberal government has introduced an array of legislative changes to segregation in the form of Bill C-56. But the legislation lacks any mention of prohibitions on placing vulnerable groups in segregation.

"Those kinds of protections should really be in legislation rather than in policy directions that can be changed rather easily," Dr. Zinger said.

The new Correctional Service rules have come into force as the prison agency faces intense scrutiny for its segregation practices in court proceedings and elsewhere.

The BC Civil Liberties Association and the John Howard Society of Canada sued the federal government in January, 2015, over the prison practice. The trial began last month in B.C. Supreme Court, with the plaintiffs arguing that segregation amounts to torture.

The Globe has reported extensively on the prevalence and effects of solitary confinement, beginning with a 2014 investigation into the death by suicide of Edward Snowshoe after 162 days in solitary confinement.

Shortly after that story was published, the Correctional Service launched a strategy to reduce the number of inmates in segregation.

The total number of segregation admissions has since fallen from 8,522 in the 2014-15 fiscal year to 6,261 in 2016-17.

Over that same span, the average time spent in solitary dropped from 34.5 days to 23.1 days.

As the Correctional Service looks to trim its segregated population further, it will face some tough decisions. Dr. Zinger said there is a federal inmate who has spent 26 years in prison – 6,184 days of which has been in segregation. He has mental-health issues, but likely doesn't meet the definition of "serious mental illness" under the new rules. Yet, he has chronic behavioural issues that jeopardize the safety of the prison when he is placed among other inmates.

"So how do you manage this individual?" Dr. Zinger said. "These are the types of challenging cases that are left. As the numbers go down further, the ones remaining in segregation will be the really difficult cases."

Patrick White

Patrick White