Melina Laboucan-Massimo, a Lubicon Cree, grew up in Alberta's oil country. Since the age of 7, she has joined blockades and protests aimed at protecting her community's traditional lands from resource development. "I was born into it," she said in an interview. "It's my inheritance."

Her parents' generation was the last to live off the land; their hunting and trapping was disrupted by the thousands of oil and gas wells that have been installed there over her lifetime. In 2011, the community's worst fears came to life when the Rainbow Pipeline ruptured in their collective back yard, spilling 28,000 barrels of light, sweet crude – the largest oil spill in Alberta in 36 years.

Forged by that experience, Ms. Laboucan-Massimo is now working at Greenpeace and throwing herself into the campaign to stop the freshly approved Kinder Morgan pipeline expansion that will dramatically increase the amount of oil-sands crude shipped through Vancouver Harbour.

She draws inspiration from the Standing Rock Sioux pipeline battle, and from protests two years ago against Kinder Morgan's Trans Mountain project when she and scores of others protested and many people were arrested.

"There are so many pledges of resistance; people are willing to hold the line," Ms. Laboucan-Massimo said of the alliance against Trans Mountain.

"Just like Standing Rock, it shows the power of the people is real, it needs to be heard. If [Kinder Morgan] puts shovels in the ground, there will be grandparents and students, First Nations and environmentalists, standing in their path all along the pipeline route, along the tanker route."

JOHN SOPINSKI/THE GLOBE AND MAIL (SOURCE: KINDER MORGAN, ESRI)

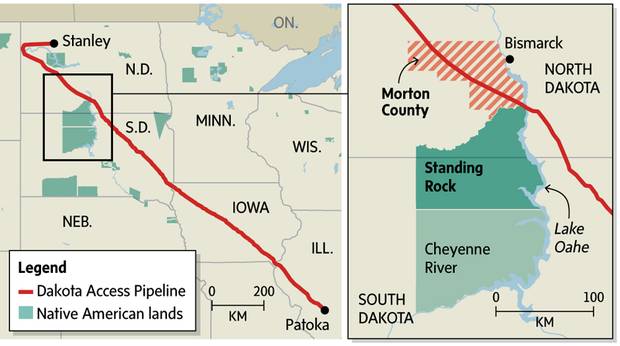

The high-profile protest at Standing Rock against the Dakota Access Pipeline has galvanized Canadian indigenous communities, who watched as one community stood up against an oil company and its powerful backers. The Standing Rock tribe was empowered by thousands of allies – indigenous and non-indigenous alike – who flooded into the area from both sides of the border to stand with the Sioux. They faced threats of rubber bullets, attack dogs and water cannons in frigid weather.

The Dakota Access pipeline’s original route would have taken it under Lake Oahe, a reservoir of the Missouri River.

MURAT YÜKSELIR/THE GLOBE AND MAIL (SOURCES: U.S. CENSUS BUREAU; ARCGIS; NATURAL EARTH DATA)

Now, some indigenous leaders are pledging to use the tactics of Standing Rock to block the two pipeline projects approved last week by the Liberal government: the bitterly fought expansion of Kinder Morgan's line that runs to Vancouver Harbour, and Enbridge's lesser-noticed plan to rebuild and expand its Line 3, a main oil export line from Alberta to the U.S. Midwest.

The rising indigenous activism – as witnessed at Standing Rock – poses the biggest challenge to the effort to complete the pipeline projects that Ottawa has approved. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau will have to balance his promise to get Canadian resources to market, on the one hand, with his commitment to First Nations' reconciliation, on the other.

Industry executives say their companies are desperate for access to markets in Asia as well as additional pipeline capacity to key U.S. refining centres. Alberta's NDP Premier Rachel Notley argues the pipelines are critical infrastructure needed to boost her province's economy, which has been devastated by the 30-month-long price slump.

But to complete the Trans Mountain expansion, the company and the federal and provincial governments are going to have to deal with First Nations communities who claim an inherent right and moral duty to do "whatever it takes" to block it.

Several First Nations have launched court challenges that assert that their treaty and constitutional rights are being violated and many leaders are promising direct action aimed at blocking construction should the courts rule against them.

The day after federal approval for the Trans Mountain expansion was announced, Ian Anderson, president of Kinder Morgan Canada, raised concerns about the safety of his workers in light of vows of continued opposition.

"We are fully and acutely aware that there are people who are saying they plan to oppose our project at all costs," he said. "What I say to them is this: Our number one and unwavering priority is the safety of our communities, the safety of my staff, our neighbours, our assets and the environment, and we will not compromise that under any condition."

There is clearly no single view among indigenous leaders on resource development.

Mr. Anderson emphasized that his company has sought, and in some cases won, consent from First Nations along the route. "We have 39 support agreements signed with First Nations communities that will bring shared benefits in excess of $300-million. I can also say that I have several more support agreements sitting on my desk right now that will increase those numbers."

At the Assembly of First Nations annual meeting near Ottawa this week, there was vigorous debate, with some chiefs arguing that communities should look to profit from oil and gas development in order to escape poverty. Others suggest companies mistakenly tout benefit agreements as expressions of support, when often they merely reflect the desire of the community to benefit from a project over which they have no control.

Among the gathered chiefs, there was widespread opposition to resource development that threatens to create environmental damage, and the assembly passed a resolution supporting Standing Rock. Several speakers portrayed the North Dakota standoff as a signature moment for indigenous people in North America as they undergo a political renaissance and assume a leading role in the environmental movement.

"We are a part of that movement that happened at Standing Rock – a lot of us have been awakened," said Andre Bear, a Cree from Saskatchewan who is co-chair of the Assembly of First Nations' youth council. "You see the revitalization that is really bursting out after years of oppression."

Mr. Bear, a student at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, visited Standing Rock in August and was impressed by the alliance of indigenous and non-indigenous people.

Justin Trudeau says two pipeline approvals good for ‘all Canadians’

While Trans Mountain has garnered much of the anti-pipeline attention, there are other potential flashpoints.

The recently formed Treaty Alliance against Tar Sands Expansion has won support from some 120 chiefs in Canada and the United States. The alliance pledges to "bar" oil-sands pipelines from crossing its members' traditional territories, and specifically mentions Trans Mountain and Line 3. But it also targets TransCanada Corp.'s proposed Keystone XL project – which is being revived as president-elect Donald Trump prepared to take office next month – and Energy East, which would carry crude across the country from Alberta to Saint John, N.B.

The alliance held an official signing ceremony during the annual meeting of the Assembly of First Nations this week in Gatineau, Que., across the river from Ottawa.

"There comes a time in our lives when we need to exercise our sacred duty to protect Mother Earth," Ghislain Picard, the AFN's regional chief for Quebec and Labrador, told the meeting. The AFNQL opposes the Energy East project, which is currently before the National Energy Board for an environmental assessment. "We have to remain vigilant and resilient because it doesn't stop here … We need to keep reminding Canadians as to the duty we have to carry."

Manitoba's regional chief Kevin Hart is also a supporter of the Treaty Alliance, and he warns that Enbridge will encounter opposition despite the Liberal government's approval. Canadian opponents are teaming up with indigenous American activists who are promising to stop the Enbridge project in Minnesota.

Winona Laduke, an Ojibwa from the White Earth reservation, is a veteran of the Standing Rock camps and has been waging the battle against Line 3 south of the border. She said that Enbridge has been misleading people by portraying the project as a rebuild of an existing line, noting it follows a new route through much of Minnesota.

The Calgary-based pipeline company is indirectly involved in the Standing Rock fight after having announced it would acquire a minority interest in the project back in August, though it has not yet completed the purchase. Ms. Laduke said that she urged Enbridge to condemn the violence against protesters but the company remained silent.

Now, the tribes in Minnesota are preparing for a showdown with Enbridge, whose route skirts the White Earth reservation's treaty area.

"They should prepare for some serious opposition," said Ms. Laduke, who still has a spot in the camp at Standing Rock. "We know how to camp, and we will stop the pipeline," she said.

People gather to protest against the proposed Kinder Morgan pipeline outside Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s office in Ottawa.

FRED CHARTRAND/THE CANADIAN PRESS

In British Columbia, coastal First Nations are among the most adamantly opposed to Trans Mountain expansion and increased tanker traffic that will result. The Tsleil-Waututh, the Squamish and the Kwantlen are pursuing legal challenges and preparing for direct action.

But Tsleil-Waututh Chief Maureen Thomas said her community wants to avoid the confrontation with police that characterized the Standing Rock standoff. "We've always tried to take the high road," she told an Ottawa news conference the day before before Ottawa approved the project. "We're not here to disrupt the rest of Canada. We're not here to cause problems for individuals."

Her nephew, Rueben George, said the community would "do what it takes" to stop the expansion, though he added that does not include violence.

Ed John, grand chief of the First Nations Summit, travelled to Standing Rock in late October in his capacity as an expert member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

In his letter of invitation, Standing Rock tribal chairman David Archambault II asked him to witness "the violence and intimidation from state law enforcement, private security as well as the North Dakota National Guard" that the protesters were experiencing as the authorities sought to break up an encampment on what the Sioux say is unceded treaty land.

Chief John said the military response to what he described as a peaceful protest created a "war zone" atmosphere. He recalled meeting fully armed officers wearing body armour. "Although they tentatively extended a hand of courtesy, I felt as though I was in an armed-conflict zone on foreign soil," he wrote in his report on the visit.

At its heart, he concluded, the conflict over pipelines and resource development is rooted in government's failure to address the inherent land rights of indigenous people.

Federal Natural Resources Minister Jim Carr argues that, in its review of the two pipeline proposals, Ottawa discharged its duty to consult and accommodate First Nations whose traditional territories will be affected by the pipelines. He believes the process will withstand court challenges.

"I think the most important value is that we're respectful," Mr. Carr said in an interview on Parliament Hill. "And that we continue to engage indigenous communities, understanding that these issues are difficult, controversial and that people have deeply held views."

The minister provoked some angry reaction last week when he told an Edmonton audience that the Liberal government respected the right to protest and dissent, but would rely on the police and military if opposition became violent. He later apologized for referring to the military, which is not responsible for domestic policing.

The comment was seen as particularly galling among the Mohawk leaders at Kanesatake, who were involved in the Oka crisis 26 years ago, when then Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa called out the military to end a standoff over a land dispute between the Mohawks and the town of Oka, Que. Then Prime Minister Brian Mulroney announced and publicly supported that decision.

After his remark, Mr. Carr called Kanesatake Chief Serge Simon, who is a key organizer in the Treaty Alliance against Tar Sands Expansion.

In the interview, the minister refused to comment on what steps the government would take to end a blockade of a construction site, or to deal with possible conflict.

"Canadians are people who understand the importance of the freedom to dissent, to take views that are different from the government's, to peacefully protest," he said. "And that is something that makes us special as a nation that we respect that right, that freedom."

Still, he added: "Canadians also recognize that we live under the rule of law."

Government security forces, however, have sometimes been accused of blurring the lines between peaceful protest and civil disobedience on the one hand, and extremist criminal activity on the other.

The Conservative government of Stephen Harper characterized those who would block resource projects as working against the economic interests of Canada, and its controversial security bill was seen as an open invitation for security agencies to spy on indigenous "extremists" who are prepared to break the law in order to oppose development.

At a symposium last month in Ottawa, security experts from government, law enforcement, industry and academia gathered to discuss "the challenges of dealing with natural-resource development projects and activism." Several speakers at the closed-door session spoke on emerging threats from the indigenous community.

An RCMP document from 2015 tracked the aboriginal protest events – largely against natural-resource projects – and identified 313 individuals who had participated in them. Of those, 89 were judged to have some propensity toward criminality, and their names are being kept in a data base.

"Some of these individuals advocate unlawful, and at times, violent protest tactics and techniques, yet there is no known evidence that these individuals pose a direct threat to critical infrastructure, the RCMP's "Project Sitka" report concluded.

One former industry executive says Prime Minister Trudeau may find his greatest challenge was not in approving the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, but in ensuring the critics do not derail a government-sanctioned project.

"The country at some point is going to have to come to terms with whether all citizens have to obey the law or not," Dennis McConaghy, a former executive vice-president at TransCanada, said in an interview. "There are limits to civil disobedience. There are limits to how much the disgruntled can challenge the decisions reached by a properly carried out, scientific, legitimate regulatory review and sanctioned by a democratically elected government."

Mr. McConachy – who has a book coming out on the Keystone XL controversy – argued no group, including First Nations, can be given a veto over decisions that governments deem to be in the national interest.

But there is a fundamental divide between that industry view that First Nations do not have a veto, which is widely supported by politicians like B.C. Premier Christy Clark, and the view of indigenous Canadians that they have an inherent right to exercise free, prior and informed consent over development that would have an impact on their traditional territory.

The Trudeau government is attempting to bridge that chasm after endorsing the United Nations Declarations on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which includes the principle of free, prior and informed consent. Mr. Carr says that principle does not provide a veto to First Nations who oppose projects, but does require companies and governments to work closely with indigenous communities to ensure they are partners in the evaluation and monitoring of projects, are properly consulted, and have their concerns accommodated.

Canada's Supreme Court – which has advanced indigenous rights in this country through a series of rulings – has not recognized the consent standard of the UN declaration. And if Mr. Carr is right, the legal avenue will not provide indigenous pipeline opponents with the answer they are seeking.

And that will leave them with the route of direct action, and the language of resistance – and, from some activists perhaps, confrontation.

Indeed, the story of Standing Rock is not over.

Under U.S. President Barack Obama, the government backed away from conflict. After ordering the activists to dismantle their camps, Washington did nothing to enforce the ruling. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which has responsibility for that segment of the Missouri River, last week handed the Standing Rock Sioux and their allies an exhilarating win by denying the company a permit to cross the river and ordering a new environmental assessment.

But with president-elect Donald Trump set to take office next month, there are no illusions that the victory will stand; Mr. Trump's Republican allies have made it clear they expect the pipeline will win approval. "The situation at Standing Rock is going to be brought to a head and it's going to get real ugly," Mr. McConachy predicted.

If he's right, Canada will be looking for new lessons to draw from the Sioux standoff.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story said the government of then Prime Minister Brian Mulroney called out the military to end a standoff over a land dispute between the Mohawks and the town of Oka, Que. In fact, the government of then Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa called out the military. Mr. Mulroney announced and publicly supported that decision. This is a corrected version.

Shawn McCarthy is the global energy reporter for The Globe and Mail. Justine Hunter is The Globe's B.C. legislature reporter. Follow them on Twitter: @smccarthy55 and @justine_hunter

PHOTO ESSAY

The view from the ground: Why Standing Rock is only the beginning

As Standing Rock protesters have endured bitter cold, water cannons and tear gas, photojournalist Amber Bracken has been alongside them. This is what she's seen

A protester meets a police blockade on Highway 1806 near Cannon Ball. Many people were injured when, in sub-zero temperatures, police deployed water cannons, pepper spray, tear gas and rubber bullets.

PHOTO ESSAY BY AMBER BRACKEN FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

"When I think about leaving I feel like I'm walking out on a ceremony that's not done. I don't feel right about it." –Wanbli Mani, Santee Sioux from Nebraska

I have been taking photographs in Standing Rock resistance camps over the past three months. When it was warmer, I would wake up before the sun and work long after it was gone. Now that winter has truly arrived, I have to work a bit slower but my routine is the same: I spend the day talking and connecting with people and their stories. They are stories of community, healing, sacrifice, family, grief, survival and most of all, determination.

The Lakota, Nakota and Dakota people of Standing Rock are tired of having their rights trampled upon in the name of "progress." Thousands of people representing hundreds of tribes and non-indigenous groups, including many Canadians, have gathered together in opposition to the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, which would transport crude oil beneath sacred Sioux land, including the Missouri River, the source of their drinking water. The last time there was a similar assembly of nations was before the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn.

In my time at the camp, I've dodged water cannons, tear gas and pepper spray while peaceful demonstrators stood fast. I've watched young Sioux and Crow men tend carefully to their horses. I've seen the gentle and absolute leadership of the Elders. I've been invited to share venison jerky, squash soups, and rice goulash made over the fire and welcomed into warm winter buses, tepees, military tents and wigwams. I've been moved to tears in a morning water ceremony led by women.

On Sunday, the Army Corps of Engineers called a halt to the proposed construction, but many feel this victory is tenuous: the company building the project is fighting the Army in court and Donald Trump made the of tapping America's oil reserves one of the centrepieces of his campaign. While some protestors have dispersed, others have vowed to remain gathered in prayer until they are certain their land is safe. The battle for the land has become something larger: a united stand for indigenous rights everywhere.

Sun and shadow move across the North Dakota plains near Cannon Ball on Standing Rock Indian Reservation. In the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, the Sioux Nation agreed to peace in exchange for exclusive use of the sacred Black Hills, and for land in South Dakota, Wyoming and Montana. The U.S. government first seized the Black Hills in 1877, when gold was discovered there. Over the ensuing decades, the government expropriated more and more of the treaty lands. Today, the land is less than half the original size.

A young woman listens to speakers after a demonstration in Bismarck, N.D., in November. Demonstrators, blocked from marching down a main street by riot police, stood and prayed for several hours before leaving peacefully.

Cousins Jiselle Ross, 8, and Ohiya Shaw, 8, wake up for the first time at Sacred Stone Camp near Cannon Ball in September. The Lakota and Ojibwa family travelled to Standing Rock from Minneapolis in part because the eldest daughter was following the issue on social media and was upset it wasn’t being covered in newspapers or on TV.

Riot police outside a Dakota Access Pipeline worker camp in Mandan, N.D. confront protestors who were drawing attention to sexual violence against indigenous women. The violence is exacerbated by the presence of the mostly male work crews that have formed temporary communities around pipeline construction sites.

A man is treated with milk of magnesia after being pepper-sprayed at a police blockade on Highway 1806, near Cannon Ball.

Hundreds of veterans and supporters march through a blizzard to pray at the Backwater Bridge police barricade near Cannon Ball.

The protest began in April. Now winter has set in, and the protesters, or “water protectors,” as they prefer to be known, must adapt to the new weather conditions.

The sun rises over a frosty camp near Cannon Ball at the end of November. Yurts, tepees, military structures, tiny homes, trailers, wigwams and other improvised structures are in use for winter shelter.

Amber Bracken is a member of the Rogue Collective of Canadian photojournalists. Follow her on Twitter: @Amber_Bracken

Q&A

Kanesatake redux: In Standing Rock, a veteran of the 1990 Oka crisis sees 'that same monster rearing its head again'

Grand Chief Serge Simon talks to Julien Gignac about pro-pipeline First Nations, anti-pipeline treaties and the news from Standing Rock

One person who deeply understands the tensions between First Nations people and the Crown is Kanesatake Grand Chief Serge Simon.

He was 28 when he lived through the 1990 Oka crisis, during which historically frayed relations were amplified to an explosive degree: In the town of Oka, Que., the Mohawk community became embattled with the provincial police force and the Canadian military to prevent burial grounds from being destroyed to make way for a proposed golf-course expansion and condominium development. Mr. Simon was guiding a small pack of journalists through the pines toward the action the morning that a Quebec police officer was killed in a barrage of bullets, he says.

Mr. Simon takes time choosing his words when asked if he fears if history could repeat itself, given the greenlighting of controversial pipeline projects such as Trans Mountain (designed to run from Edmonton through B.C. to the Pacific Coast) and Line 3 (meant to boost capacity on an existing route to the U.S. Midwest), which could likewise encroach on indigenous titles and rights.

"I hope and pray it doesn't. I cherish peace above all. I don't want to advocate another Oka crisis," he says over the phone from Gatineau, Que., a day before an Assembly of First Nations conference.

In Edmonton during the last week of November, Natural Resources Minister Jim Carr said that military and police forces could be used to subdue anti-pipeline protests for the sake of public safety.

Says Mr. Simon, referring to those remarks: "I spoke to many chiefs and they see it as a direct threat." But he adds that, before the AFN meeting on Tuesday, the minister phoned him to apologize for his remarks.

Mr. Simon, working alongside numerous chiefs across Canada, has devised a more pacifist mode of opposition: a treaty that would bolster the lobbying power of indigenous people against energy developments such as Alberta's oil sands.

As an instrument of unification, the Treaty Alliance Against Tar Sands Expansion includes more than 100 signatories, including David Archambault II, the chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe. The treaty seeks to preserve and protect what is sacred to them.

"It's a treaty of mutual support and protection between chiefs and respective territories that we're going to resist any attempts at the expansion of the tar sands," he said. "It's becoming increasingly dangerous, not only for First Nations around Alberta, but also for the entire Canadian population and the world. It's some of the dirtiest oil on Earth."

Mr. Simon had a part to play in the protests against the Dakota Access pipeline: He sent a letter to U.S. President Barack Obama, he says, "demanding he do something before it got out of hand."

This week, Mr. Simon spoke to The Globe and Mail about indigenous initiatives to fight pipelines, the situation in North Dakota, and what he sees as echoes of the Oka crisis.

How are you feeling about last weekend's news from Standing Rock?

I am feeling relieved about the decision. It's more of a stay of execution. Like, we're not going to kill you today. At Standing Rock, they have a good argument, but [U.S. president-elect Donald] Trump made it clear when he becomes president he's going to give [the developers] the permit – forget about the environmental assessment, or the economic-impact assessment that the Sioux have been demanding.

What do you and your allies plan to do about the Trans Mountain and Line 3 pipeline projects?

We're talking about a chiefs' alliance, the governing bodies of every respective territory that signs. We're not the grassroots. We could look at lobbying internationally. We could look at the possibility of charging Canada at the International Criminal Court and lobbying international partners, such as Germany, Portugal, Spain, whoever we can have who would be sympathetic to the First Nations here and whatever it is we're fighting. We are First Nations, not first communities or municipalities. We were a nation long before Canada was created, and I think we'll be nations long after it's gone. Investing further into the tar sands is equal to investing in the company that made the last buggy whip.

There are some First Nations who are pro-pipeline. What do you have to say to them?

They don't have to be. There are alternatives out there. If you want to diversify your community's portfolio, look elsewhere.

How do you respond to the fact that many First Nations are financially strapped and could benefit from these projects?

I'm sitting here with the same damn boots I came into the office with five years ago. My community is also poor. But it will not submit to irresponsible development as a means of making money. My community has a little more integrity. I'm not saying others don't; they're just not informed about what's really going on. Poverty, yes, is a huge incentive to sign on the dotted line. And whose fault is that? The Canadian government's.

National Chief Perry Bellegarde's position on the matter of energy development and indigenous people is neutral. How do you feel about this?

I think Perry is trying to do the best he can in view of Alberta and the First Nations that are benefiting. But then he also has to take into consideration those that are not and those that are just getting all the negative health impacts.

Tell me about your experience during Oka.

I was involved with bringing food from the Oka village. I was taking these little trails I knew through the bush and trying to smuggle food up there. I was there that morning when the shooting started. Just as we crossed the field to where the barricade was, we smelled the teargas, saw band members running away. Next thing I heard was a "pop pop." Then all hell broke loose.

That's when we dove into the sand. We could see the [Sûreté du Québec officers] running between trees. They were running like hell. [Afterward], I was sitting around a pickup truck with a few guys listening to the radio and all of a sudden the news comes out saying a police officer has been shot and killed at Oka. Our jaws dropped. If one more person died on either side, I think you would have seen a civil war erupt in this country.

What lessons did you learn from it?

I saw firsthand when respect and dialogue fail. When the rule of law, when it comes to our treaties and the promises that were made, when those are broken, that's what happens. And that's what we're seeing again. We're seeing partially that same monster rearing its head again. No dialogue, no respect, absolutely no recognition of the law with regards to First Nations and their titles and rights. We can live in peace between the non-native society and ours, like we've always intended through our treaties.

Let's say if Canada did to France what they did to First Nations: They would call that an act of war.

Julien Gignac is a reporter at The Globe and Mail. Follow him on Twitter: @JulienGignac

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL