Nathanael Flinn has a dilemma.

The Grade 10 student at Smiths Falls District Collegiate Institute has been part of a national "hackathon" designed to introduce young Canadians to the significance of such key First World War battles as Vimy Ridge and Hill 70.

Using computer websites, e-mail, archives and old-fashioned telephone and books, the students are tracking down individual soldiers who served, and were often killed, in the Great War. The intent is eventually to build a massive database of soldier biographies.

In essence, it is "Lest We Forget" in action.

Nathanael chose a young man, not much older than himself, a soldier who saw action at Vimy. Like all the other students in Eric Marsland's Grade 10 Canadian history class, he used ancestry sites to track down relatives, government and military sites to access "primary evidence" such as the "War Diary or Intelligence Summary" kept by each battalion, as well as the medical and service records of the individual soldiers, and from all that research began building a file on his chosen subject.

As he researches, another teacher, Blake Seward, who specializes in military history and has led teacher and student pilgrimages to the Canadian battlefields of Europe, put the service record of another Canadian soldier, Elton Megart, up on a large screen to illustrate how the students could begin with the primary research material.

Elton Megart's story is, sadly, typical. He was only 19 when he enlisted, only a few years older than the students of Mr. Marsland's class. There was a local connection as Megart had lived on a street in Smiths Falls, and the students have already used Google Earth to locate the home and are now hoping to track down period photographs of the property at the time of the Great War. He is listed as "single," next of kin named "Mary Megart," his mother. He arrived in England on "6-10-16" on the SS Lapland and was deployed to France. On April 9, 1917, at Vimy Ridge, he was listed as "Killed in Action."

Nathanael Flinn's soldier had a rather different story. His first two names were "Charles James," his surname known but not mentioned here. Nathanael gathered what information he could from the archives and found a service record that ended with the abrupt notation: "S.O.S. as deserter."

"S.O.S" in this instance stands for "Struck off Strength" rather than "save our souls" – the soul of Charles James to be decided by other, higher offices.

The decision to share whatever information that is gathered – as other students are happily doing with grateful families across the country – becomes Nathanael Flinn's dilemma.

"I'd have to think about it," says the 15-year-old student. "It's rough. If they were under the impression that their grandfather was a great war hero I wouldn't want to crush that."

Above: Red Cross workers at Vimy Ridge render first aid to an airman brought down within his own lines. Below: A driver of the first aid nursing yeomanry cranks up the engine of her ambulance in November, 1917.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

The students work in a large room largely lighted by the glow from two dozen or so laptop computers. The art on the wall is a depiction of Juno Beach, the June 6, 1944, landing that was so important to victory in the next world war. Previous students in this and other schools were able to compile biographies of 359 Canadian soldiers who died storming the beach, the information today instantly downloadable to mobile phones via QR codes on plaques that have been mounted at the Juno Beach Centre in Courseulles-sur-Mer, France.

There are flags hanging from the classroom ceiling – the Union Jack, the flag of France, America's Stars and Stripes, the Soviet Union's hammer and sickle, the Canadian maple leaf – and photographs of poppies and war cemeteries. There are several games of "Risk: The Game of Global Domination."

Amy Dolan, 15, has been researching the life of James Charles Dolan, her great-great-great grandfather who fought at Hill 70 and survived the war. The family has been able to supply everything from photographs to detailed information on what must have been a fascinating life: an adventurous young man who left the family farm at 14 to head for the sea and a life on a whaling ship.

Amy's research, however, has brought other things to light. His service record suggests he was clearly a rambunctious soldier – at one point assigned five days of "field punishment" for disappearing for several hours and showing up drunk.

His medical records indicated he was heavily tattooed, including fish tattoos over each foot – mementoes, surely, from his whaling days – and that there was a "large brown mole on left buttock."

"I don't think I needed to know that," she says.

Grace LeSurf, 15, chose a soldier with the romantic name of Lancelot Maurice Attwood, who was a member of the 116th Battalion of Lethbridge. She was able to make contact with a granddaughter, Barbara Bergman, via e-mail, and learned fascinating new details of what had happened to Lancelot at Vimy Ridge.

Ms. Bergman wrote back to say her grandfather had been shot in the head about two hours into the Battle of Vimy Ridge and died in the arms of his best friend, Peter Auld, who later wrote to her grandmother with details.

"My mother never knew her father," she wrote. "He died when she was just months old. My grandmother never talked about her husband… My grandfather's death had a profound effect on my grandmother and mother and they carried those scars throughout their lives."

The exchange provided Grace with details she had not known. Peter Auld had been able to tell the family that Lancelot had been buried in a mass grave with 43 other soldiers and this mass grave, thought to be in a potato field, had been overlooked when crews later came along to exhume bodies from such sites and give the soldier proper burials.

Norm Christie, an Ottawa military historian, has launched "Help Recover Our Vimy Heroes," an online fundraising campaign to have the 44 remains, believed to be in mine crater CA40 in "No Man's Land," exhumed and given proper military reburials. So far, about half the hoped-for $110,000 goal has been raised.

The students researching soldiers who fought at Hill 70, near Lens, France, also work with an impressive educational kit, "The Battle of Hill 70," which is part of The Hill 70 Memorial Project to have this forgotten battle take its proper place in Canadian history. As well as a teacher's guide, the kit includes books, graphic comics, information on various soldiers and officers, artwork, poetry written during the battle, official battle maps, period photographs, recruitment posters, even a copy of the original "Provisional Instructions Regarding Precautions Against Hostile Gas Shells."

Battle for Hill 70: Everything you need to know in under three minutes

All the research, says Mr. Seward, is provided to the students "with no narrative – they get to determine the narrative."

As the information is gathered, it is input into a growing database. The national "hackathon" is studying 1,780 soldiers in detail and, so far, they have made some interesting discoveries.

"One of the myths is that they were all farm boys," says Mason Black, who teaches computer science at the school. "The data shows they came mostly from urban areas."

Mr. Black had spent more than two years on the project and has overseen the production of an impressive "virtual tour" of the Vimy Memorial, the 30,000 lines of coding in the program built by students such as 16-year-old Oksana Johnston.

"A lot of people said you can't do that, that it goes beyond the capabilities of the students," says Mr. Black. "Well, they're doing it."

Sixteen-year-old Melrose Yurkiw asks Mr. Seward: "Okay if I make a couple of phone calls?"

She wants to call the town hall in Amherst, N.S., to see if she can get address details on Alfred Sylvany Cormier, who is a distant relative. He had joined up when he was 18, only two years older than this young woman who would, she believes, be his great-great-great grandniece. He was with the 25th Battalion and was only 21 when he died, having been wounded in his lungs and evacuated from the front line before, as the official report has it, he "succumbed to his wounds."

Melrose is connecting strongly to this young man. Her grandmother lives in Amherst and has been able to supply various information and photographs, even a picture of his faraway grave. Alfred had worked as a farmer, a shoemaker and a clerk before signing up.

"You learn that this isn't just a person, a soldier that died, just another number," says Melrose. "This was a person who had a family, a home, people who loved him.

"If I was a soldier, I'd want someone to do this for me."

So involved has she become with researching this young man who was part of her family that she feels she has come to know him personally. "I like him," she says. "I look up to him. I'm so proud of what he did. He was 18 and he went so far in the war. He almost made it. With the technology we have today, he likely would have been saved."

She now believes she knows what she will do with her own precious life.

"I want to be a nurse," she says. "I want to take care of people."

VERBATIM

A letter from the front

CANADIAN LETTERS AND IMAGES COLLECTION/VICTORIA ISLAND UNIVERSITY

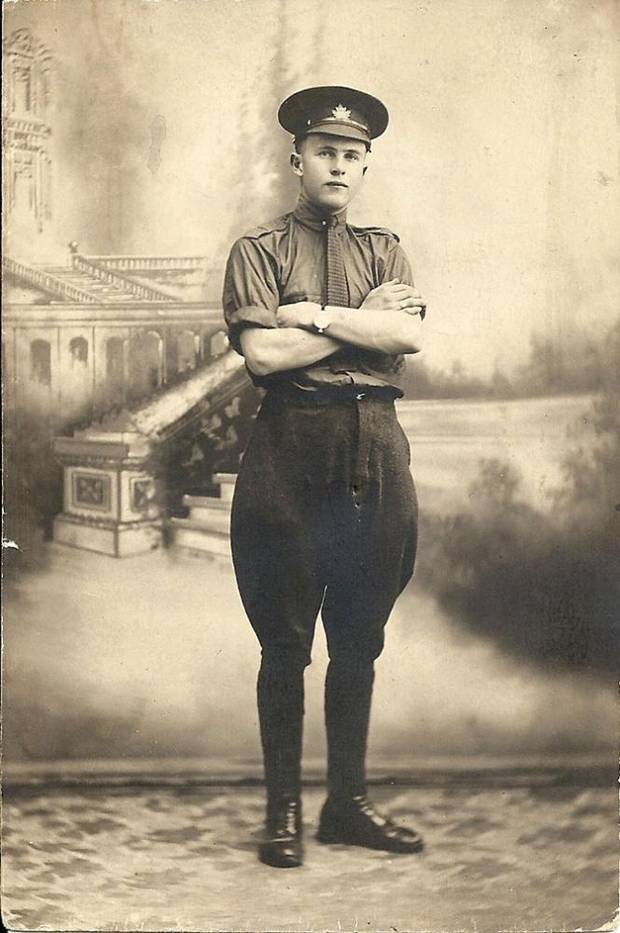

Clair Barrey, pictured above, was in the 7th Battalion fighting at Hill 70 when he was wounded and had his right leg amputated. The following is a letter he sent to his family. The letter is part of the Canadian Letters and Images Collection from Vancouver Island University.

Dear Sister and All,

Just a few lines to let you know that I am getting along fine and have pulled through my operation splendid, so the doctors tell me. I think Father Omora wrote you the other day and told you the news of my misfortune in being wounded with shrapnel in the right leg. It had to be taken off about the knee.

I have a great deal to be thankful for I can tell you Agnes, so do not worry about me. I am in hospital in France yet, but will be leaving for England any day now. In the course of a few months I will be home in Canada if all goes well, by the will of God.

I know it must be a great shock to you, but I think it is all for the best. It was God’s will or it would not have happened, don’t you think so Aggie?

I know you would think I was lucky if you could see some of the poor fellows here all shot to pieces. The Sisters use me fine here though, as do all the hospital staff.

We had quite a few casualties in our batt., but they were mostly wounded. We went over the top after Fritz about 4:25 a.m., but he was up against Canadians and so he failed.

The priest comes in to see me two or three times a day, so please don’t worry about me, as he says I am getting on wonderfully.

It is now August the 19th, 6 p.m. I don’t know when I will go to England, but it will be any day now. You had better not write to me until you get my address from there, as it will not find me. I will write as often as I can, with love to all.

I remain your Son and Brother, Clair

CANADA AT WAR: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL