The early morning sky is bruised purple and black – rain has fallen through the night and will soon fall again – but the mood is sunny, always sunny, as Andrew Scheer walks six-year-old Henry to the boy's flag-football game on the outskirts of the city. Here, the son will show the same grinding, quiet determination that more than four months ago made the father the surprising new leader of the Conservative Party of Canada.

When the results of that 13th ballot were announced, Mr. Scheer became the 46th person to hold the curious job of leader of Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition. Many are today long forgotten – Daniel Duncan McKenzie's six months in 1919 – but some held onto their jobs for considerable stretches. Wilfrid Laurier led a Liberal opposition for nine years through four prime ministers before he became PM in 1896. Robert Stanfield became opposition leader in 1967 and stayed eight-plus years without ever landing the big job.

Such patience is, however, a thing of the past in Canada. There have been 13 leaders, some acting, of Her Majesty's Loyal Opposition since 2000. Mr. Scheer arrived on the national stage almost completely unknown, to most Canadians a Nowhere Man not sure where he's going to. Voters unsure, even, as to where he came from – east or west?

Slowly, oh so slowly, he has been coming into faint focus, but speed is now of the essence with two federal by-elections, both currently held by the Conservatives, slated for Oct. 23. The Alberta seat, Sturgeon River-Parkland, was previously safely held by interim party leader Rona Ambrose. The Quebec seat, Lac-Saint-Jean, was held by retiring Member of Parliament Denis Lebel, who squeaked back into office with only 33 per cent of the vote two years ago. Lac-Saint-Jean will be a significant test for Mr. Scheer.

The new leader began as a blank sheet that his party envisioned as filling with hope for a return to power in 2019. The governing Liberals, on the other hand, had hoped that sheet would soon fill with deeply conservative stances that would largely turn off voters. Mr. Scheer, after all, has been anti-abortion, anti-gay marriage, as well as very much opposed to the possibility of a carbon tax, which he says will "kill jobs in Canada. It will hurt low-income Canadians."

That sheet, however, remains blank enough that, as of this past week, neither Mr. Scheer's home page nor The Canadian Press's Web page on him say anything about his positions on a long list of issues. It appears that he is deliberately modelling his leadership after former prime minister Stephen Harper, who succeeded in no small part because he refused to go down several controversial paths, regardless of his own convictions. When Mr. Scheer was asked this spring about his stance on the legalization of marijuana, for example, his response was that both he and the party have to be "realistic."

Mr. Scheer has been called "Harper lite" and "Harper with a smile and dimples" – a social conservative who nonetheless avoids extremism on social issues. As an MP, he had a pro-life voting record in Parliament – and also voted against Bill C-14, the medical-assistance-in-dying law. Since he has become party leader, though, he has determinedly avoided such issues. It is impossible, at this point, to produce a comprehensive list of what he does and does not stand for.

As summer turned into fall, Mr. Scheer found himself happily railing on against the government's (weakly communicated) tax-reform efforts, and tying Conservative Party fortunes to those doctors and farmers and small business owners who see those reforms as a direct attack on them. "As Conservatives," he told the House of Commons late last month, "we believe in raising people up, not tearing people down. Conservatives wake up every day trying to think of new ways to lower taxes. Liberals wake up every day trying to find new ways to raise taxes."

Will Mr. Scheer be able to ride a simmering anger and widespread confusion about tax reform to victory in the two by-elections, or will he stumble over such sideshow issues as Senator Lynn Beyak's ignorance on Indigenous issues or the sexist tweets of newly retired Saskatchewan MP Gerry Ritz? That Mr. Scheer can be slow to act was evident in his handling of these two controversies. It didn't help that he seemed to drag his heels in distancing himself from ultraconservative and highly controversial Rebel Media – even as it appeared to legitimize white supremacists – on which he and other conservative MPs had enthusiastically appeared.

His most decisive act, so far, has been the formation of a shadow cabinet: He gave Maxime Bernier – whom Mr. Scheer narrowly outmanoeuvred for the party leadership – a significant role (innovation, science and economic development). And he offered nothing to Kellie Leitch, the leadership candidate who during the 2015 federal election had called for an RCMP tip line on which Canadians could report "barbaric cultural practices" and who led a controversial leadership campaign centring on "Canadian values" and immigration.

Blushingly polite

When Mr. Scheer defeated the much-better-known Mr. Bernier back in May, he told the crowd: "The Liberals can take their cues from the cocktail circuit. We will take ours from the minivans, from the soccer fields, from the legion halls and the grocery stores."

This day in Regina, in the only province where football challenges hockey as the sport of highest passion, Mr. Scheer prowls the sidelines wearing a Seattle Seahawks hoodie over a green golf shirt with the Saskatchewan Roughriders logo over his heart. He cheers for the Seahawks because the National Football Team's punter, Jon Ryan, is not only from Regina but is the brother of Mr. Scheer's wife, Jill. He cheers for the Roughriders because if you're going to call this province home, you'd better bleed green.

While Henry and his quick little teammate Pierre Potgieter combine for touchdown after touchdown in the little-league match, Mr. Scheer makes his own scores working the parents along the sidelines. Naturally friendly, but shy, he had to learn to be gregarious from Jill, whom he followed West to marry after university in Ottawa. Jill can work a room in ways he can only hope that practice will one day bring him.

One set of sideline parents, both physicians, have come to Saskatchewan from the United States. Dr. Sanaz Dehghani, an expert in internal medicine, concedes that she knows absolutely nothing about Canadian politics.

"Well," Mr. Scheer tells her as the blackened sky begins to spit, "I'm the leader of the opposition in Parliament. And in the next election, if my party wins more seats than the other parties, then I would become prime minister."

She listens patiently along with her husband, cardiologist Dr. Payam Dehghani, and her eyes grow wide with curiosity. "But," she says, "you're too … too nice … and quiet. If this was America, you'd be a lot louder and" – she slams her fist into the open palm of her other hand, laughing.

Blushing, Mr. Scheer laughs with them, but he also knows she is right. "The election is two years away, but it begins right now for me," he tells the two doctors. "I have to get out more.

"I have to work on name recognition."

It appears that Mr. Scheer is deliberately modelling his leadership after former prime minister Stephen Harper, refusing to go down several controversial paths, regardless of his own convictions.

SEAN KILPATRICK/THE CANADIAN PRESS

A Romanian revelation

Beth Grainger knows everyone's business in little Fort Qu'Appelle because she has so much of it. Her popular floral and gift shop is in the centre of town, directly across Broadway Avenue from Andrew Scheer's rural constituency office. "He's accepted as one of our own," she says of the 38-year-old Ottawa native, who wrested the riding of Regina-Qu'Appelle from the New Democratic Party's formidable Lorne Nystrom 13 years ago and has held it now through five federal elections, serving as Speaker of the House from 2011 to 2015.

"He doesn't come with suits or staff or anything. He just comes as he is. He's one of us."

There is no "come from away" culture in Saskatchewan, where, with the significant exception of the 70 First Nations – 12 of them in Mr. Scheer's riding – everyone is one or a small handful of generations removed from elsewhere.

Even so, Andrew Scheer is unique: an Ontario city boy who, early on, had to ask Prairie voters what crop it was that they were growing. Today he knows how to distinguish wheat from flax.

He was born May 20, 1979, the middle child of Mary and James Scheer, sister Catherine older, sister Anne Marie younger. The family was, and remains, religious: Jim Scheer, a retired librarian with the Ottawa Citizen, serves as a deacon with the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Ottawa. Andrew's mother, a long-time nurse with the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario, passed away less than three months before her son won the party leadership.

In the four years that Andrew Scheer served as Speaker of the House of Commons – only 32 years old in 2011, he became the youngest Speaker in Canadian history – he met heads of state and royalty, yet ranks as his greatest thrill the day he shook hands with Alex Trebek, the Canadian-born host of the television game show Jeopardy! "It was a ritual in our house," he explains. "We'd eat dinner, talk about the day and then watch Jeopardy! You couldn't watch with my Dad – you hadn't even finished reading the question and he already had the answer."

Andrew played baseball, but sports was only a side interest, hardly a passion. What he loved was politics. When at age 9, he began delivering the Ottawa Citizen, then an afternoon paper, his first stop was himself: He would read the newspaper from front to back.

He can even pinpoint the exact moment when he knew that politics would be his life. He had sat down to pore through the first edition of the Citizen following the Christmas Day, 1989, execution of Romanian leader Nicolae Ceausescu. "In the mind of a nine-year-old," he remembers, "your own team doesn't take you out."

He began watching the news every evening as well as reading the newspaper. He admits to skipping class to race down along the Rideau Canal from high school to Parliament Hill, where he would watch Question Period. He was in computer class one day when he landed on the Reform Party website. "There was a link to Reform Youth," he says. "You could send a message to the youth co-ordinator, so in the middle of the class I sent a message saying 'Hey, I'm interested in politics. If you ever have anything going in Ottawa let me know.' I got an e-mail back that night. I met with the youth co-ordinator, and ever since then I've been involved."

He worked on Preston Manning's campaign for the leadership of the new Canadian Alliance. He was on the youth team at the United Alternative convention in 1999.

He even sought office himself, running for the Ottawa Catholic School Board while still an undergraduate at the University of Ottawa, where he studied history. "I just decided to give it a shot," he says. "Three or four friends helped me hand out leaflets and put up a few signs. I got 17 per cent of the vote, which wasn't bad, considering."

At university he had met and fallen in love with Jill Ryan, who let it be known that she would be returning home to Regina and that if he wanted to continue the relationship he would have to move west. He did, at first waiting on tables in downtown Regina. A year after he arrived they married, and today have five children: Thomas, 12, Grace, 10, Madeline, 8, Henry, 6, and Mary, 22 months.

Almost immediately upon his arrival in Regina he became involved in provincial politics, helping the Saskatchewan Party place a strong second in the 2003 campaign. He worked hardest for the campaign of Mike Shenher, running in the riding of Regina Walsh Acres.

"Mike said to me, 'If this doesn't work out for me, you should run federally,'" Mr. Scheer recalls. "I said 'Come on!' Anyway, the Saskatchewan Party didn't win that seat. He kept pushing me. 'You've got to give it a shot,' he'd say."

Mr. Scheer worked briefly as an insurance broker before signing on as a constituency secretary for Regina-Lumsden-Lake Centre Alliance MP Larry Spencer, who was soon booted from the party for controversial remarks about homosexuals.

The 2004 federal election was looming, Mr. Shenher was still pushing, and so 25-year-old Andrew Scheer, a solid supporter of Mr. Harper, now leader of the newly merged Conservative Party, decided to run. It was, to say the least, a long shot. The riding he chose in which to seek the nomination was Regina-Qu'Appelle. It was owned, it seemed, by the NDP's Nystrom, who first won the seat when he was only 22, and by 2004 had become a Saskatchewan institution, having spent 32 years as a Parliamentarian.

"I decided to throw my hat in the ring," says Mr. Scheer. "I had a sense that the NDP at that time was really losing touch with the Prairie populist roots that had been part of the movement for so long. People were saying that under Jack Layton it had become more Toronto-based."

He won the Conservative nomination and promised to "work hard. I never tried to pretend that I knew everything. If I didn't know something, I asked them to explain it to me."

A 'pathetic' accusation

Lorne Nystrom, now 71 and still sporting a youthful shock of blond curls, says he holds no bitterness after 13 years out of office. A successful entrepreneur working largely with Chinese companies, he has no further political ambitions. Mr. Nystrom believes he lost his seat due to a not-uncommon desire for change, a stronger than expected showing from the Liberals – and, something he still regrets, an ugly exchange with Mr. Scheer near the end of the campaign when the young challenger suggested that Mr. Nystrom was soft on child pornography.

Mr. Nystrom had indeed expressed concerns about a threat to "artistic merit and freedom of expression" – citing Vladimir Nabokov's 1955 novel Lolita as a prime example – during a Commons debate aimed at closing loopholes in such legislation; but any suggestion that he was therefore "soft," he says, was "absolutely outrageous. To accuse somebody of defending child pornography is just pathetic."

Mr. Scheer refused to back down, telling the media that "people are going to be scratching their heads and asking, 'What forms of child pornography have artistic merit?'"

Mr. Nystrom says that two lawyers advised that he had grounds for a defamation suit, but he decided to move on after the loss, which he preferred to put down, in the main, to a split vote: Well-connected Liberal candidate Allyce Herle, with the party machine behind her and prime minister Paul Martin paying visits to the riding, snagged 2,687 more votes than the Liberals had managed four years earlier – far more than the 861-vote margin by which Mr. Nystrom lost to Mr. Scheer.

Still, Mr. Nystrom says the pornography issue demonstrates that the ever-smiling Mr. Scheer can at times be "more nasty than you would think."

Mr. Scheer's harshest critic through his early years in Saskatchewan turned out to be a fellow Alliance-Conservative he had worked with, Larry Birkbeck, a former member of the provincial legislature who had served as chief of staff for Larry Spencer. Mr. Birkbeck, who died in 2016, ran a blog that could, at times, be harsh. When Mr. Scheer launched his first re-election campaign heading into the 2006 federal election, Mr. Birkbeck wrote, "The voters should not forget that Andrew Scheer is an Ottawa boy, who came to Saskatchewan shortly before the election, who knows little about Saskatchewan, who knows even less about agriculture, who has a few months of business experience, who has no degree or special education, who referred to our provincial government as a socialist/communist regime and who is a boy badly in need of some sound Saskatchewan political advice."

In another blog, Mr. Birkbeck said he "would not vote for Andrew Scheer because I know him better than most. I have never been a supporter of self-appointed intellects." If Mr. Scheer were to lose, he predicted, he would immediately hightail it back to Ottawa.

Mr. Scheer did not lose, of course. He won and headed to Ottawa as a Saskatchewan MP, part of a new wave of young Conservatives arrived in Ottawa in 2004. Bilingual (thanks to his Ottawa education), the new member became fast friends with David Batters, a young businessman who had won the Saskatchewan riding of Palliser. Mr. Scheer joined others who were helping Mr. Batters deal with depression, but they were not successful. When the MP took his own life in the summer of 2009, Mr. Scheer was one of the pallbearers at his memorial.

Denise Batters, the MP's widow, was appointed to the Senate by Prime Minister Harper in 2013 and has since devoted herself to mental-health issues. She became one of Mr. Scheer's most enthusiastic and vocal champions.

Ms. Batters was there this past May when the leadership voting got under way in Toronto. "Andrew was smart enough that he could see the strategy the team should employ: Aim for silver, count on gold," she recalls. "Many Conservatives were saying they had Mr. Scheer as their No. 2 choice, meaning, if the front runners slipped, he might himself slip up the middle and pass the other dozen candidates." Ms. Batters predicted to the CBC that Mr. Scheer would win it on the 13th ballot – and he did so, by less than 2 percentage points over Mr. Bernier.

"He's been underestimated his whole career," says the Saskatchewan senator. "He's going to be a perfect foil for Justin Trudeau next election. Canadians are going to have had enough of celebrity politics by then."

She says she wept when Mr. Scheer took the stage to claim his victory. And she cheered when he opened his first caucus meeting by evoking the memory and words of John Diefenbaker, Canada's 13th prime minister and also an MP from Saskatchewan. "He told us he wouldn't apologize for speaking up for hard-working Canadians," says Ms. Batters. "He said, 'I'm one of them.'"

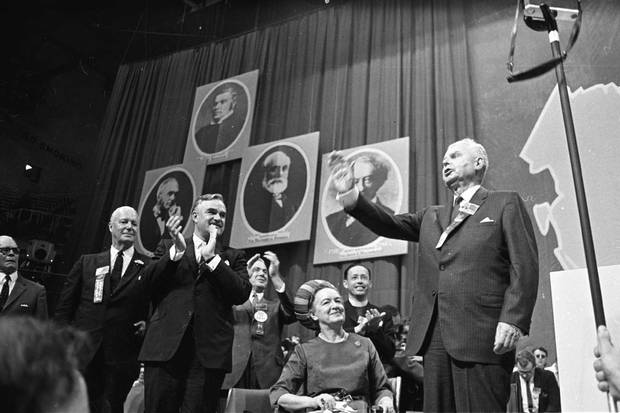

Sept. 7, 1967: Progressive Conservative leader John Diefenbaker, standing beside his wife, Olive, speaks at the party convention at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens, where he lost the leadership to Robert Stanfield.

HAROLD ROBINSON/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

May 27, 2017: Andrew Scheer, newly elected as Conservative Leader, speaks at the party convention in front of his wife Jill; baby daughter Mary; sons Thomas, 12, and Henry,6; and daughter Grace, 10. Mr. Scheer’s victory speech referenced the defeated Mr. Diefenbaker’s speech from 50 years earlier.

FRANK GUNN/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Like Dief – and not

Here, high on the eastern banks of the South Saskatchewan River as it flows through Saskatoon, lies John George Diefenbaker, 1895-1979, and his wife Olive Evangeline, 1902-1976. The grounds are lovingly cared for, though the planted flowers have no chance against the half-dozen prairie dogs that stand and stare curiously at visitors to the Diefenbaker Canada Centre.

The quotation Mr. Scheer referenced in his opening address to caucus came from something Mr. Diefenbaker had said on Sept. 7, 1967, as he was losing a nasty battle to hold on to the leadership of the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada. "They criticized me sometimes for being too much concerned with the average Canadian," Mr. Diefenbaker said. "I can't help that. I'm just one of them."

Many of today's Conservatives like the link, however tenuous, as they see Mr. Scheer trying to appeal to ordinary Canadians who had to make their own way in the world, unlike Justin Trudeau and his privileged upbringing. Mr. Diefenbaker, as well, was Ontario-born and became a Prairie populist.

But the comparison is a bit of a stretch. Mr. Diefenbaker may have been born in the village of Neustadt, Ont., but from age 8 on he lived in what would soon become the province of Saskatchewan, first on a farm near Borden and later in Saskatoon. Mr. Scheer was educated in Ottawa and, obviously, had none of Mr. Diefenbaker's homestead experience.

There are precious few telling anecdotes in Andrew Scheer's life. He did, during one campaign, win an apple-pie-baking contest at the Abernethy Agricultural Fair and Exhibition. And while living in the Speaker's home with Jill and their growing, rambunctious family, there was the moment he had to phone Douglas Richardson, Saskatchewan trustee of the Canadiana Fund, which overseas the loaning of art owned by Canada. One of the Scheer children had rammed a pencil through a painting, which was easily repaired.

"The Speaker was genuinely worried," remembers Mr. Richardson.

Certainly Mr. Scheer has nothing comparable to Mr. Diefenbaker's story of being a paperboy the day Wilfrid Laurier passed through town and stopped to chat. ("Sorry, Prime Minister," the young Diefenbaker said, "but I can't waste any more time. I've got to sell my papers." True or not, the charming anecdote merits its own statue in downtown Saskatoon.)

Mr. Diefenbaker was a fiery, commanding orator – Mr. Scheer not so much, though he has a folksy manner. He was born only a few months before Mr. Diefenbaker's death, but it is more than generations that separate them. Mr. Diefenbaker was progressive – he introduced a Bill of Rights, opposed apartheid, stressed the importance of the North. Mr. Scheer is a social conservative whose political views have yet to be fully revealed. "The fundamental thing for me," he says, "is that every kind of conservative has to have a home, but that the leader has to focus on the issues that bring us together. No conservative is going to get 100 per cent of what they want."

"My pitch to members during the campaign was, if you have two sheets of paper and on one you write down all the things that Conservatives can't agree on and on the other all the things we do agree on, which should be tackled first? We can get far more progress if we just agree to work on these things. We don't have to reinvent ourselves."

Mr. Diefenbaker first came to power in 1957 with the simplest of slogans – "It's time for a Diefenbaker government" – and, conceivably, a variation of that could serve Mr. Scheer well, as Canadians are far more adept at tossing governments out than putting them in.

Mr. Diefenbaker's and Mr. Scheer's narrative might find some common ground should the new Conservative leader win the federal election in 2019 – and have to deal with the Donald Trump administration in Washington. Mr. Diefenbaker was defiant when it came to Canadian-American relations, particularly over such matters as the Cuban Missile Crisis and North American defence plans. As a wall post in the Diefenbaker Centre puts it: "Never had relations between a Canadian Prime Minister and an American President been as strained as they were between 1961 and 1963." His appeal in the age of John F. Kennedy was a populist one, which today has taken on a somewhat twisted meaning when applied to Mr. Trump and the confusing, divisive culture of battling "news" interpretations.

One Prairie activist who understands traditional populism is David Orchard, the Saskatchewan grain farmer and anti-free-trade campaigner who was once a pivotal force in Canadian conservative politics. Mr. Orchard even ran for the leadership of the Progressive Conservative party in the days before the merger with Reform-Alliance, which he opposed.

Mr. Orchard is today not affiliated with the party, yet his many and dedicated followers still consider themselves conservative and represent votes Mr. Scheer would hope to sway. Mr. Orchard believes the timing is ripe for populism in Canada. "There is tremendous disillusionment," he says, "with our political parties." He contends that the main parties have turned a blind eye to a "wholesale torrent of takeovers" – from retail to coffee chains – that is turning Canada into "the largest colony in the world. And it's not being talked about by any of the parties. It's a monstrous problem."

As for the North American free-trade agreement, which Mr. Orchard has fought against since the late 1980s, he is adamant that the current renegotiation of NAFTA requires a far different response from Canada than has so far been evident. "We're going to get sold out even more," he fears.

He would like nothing better than to see a modern John Diefenbaker tap into such disenchantment with the status quo. "He stood up to the United States of America," Mr. Orchard says. "What political leader do we have who will stand up to the United States?"

Mr. Scheer believes he can – at least, he thinks, far better than Mr. Trudeau has so far. In the summer, he accused the Prime Minister of showing more interest in striking a trade deal with China – "which nobody wants" – than he has in protecting the softwood lumber industry.

"They're not working hard enough on this NAFTA file," said Mr. Scheer. "I think they've mishandled the trade file."

‘I would venture a guess that when an opposition leader comes in, there’s always a hurdle there,’ says Mr. Scheer. ‘We may be well known within the party membership but not much farther.’

FRED CHARTRAND/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Up against the image guy

Andrew Scheer is very open about his need to work on "name recognition." Talking to people in his Regina-Qu'Appelle riding, both in the city and countryside, elicits a common refrain: "He seems like a really nice guy, but I can't say as I really know him."

"Joe Who? Andrew Who?" says Lorne Nystrom, recalling that, back in 1976, new Progressive Conservative leader Joe Clark was equally unknown just three years before being elected prime minister. "He's not really noted for anything in particular."

Andrew Scheer says, and has to believe, that that will change as he travels the country and establishes himself as an alternative to Justin Trudeau. He knows he needs to become known, and quickly, for something other than his dimples and chipmunk smile. The two by-elections are barely two weeks away. "I would venture a guess that when an opposition leader comes in, there's always a hurdle there," Mr. Scheer says. "We may be well known within the party membership but not much farther.

"This current PM is an image-driven politician. So he's got that and he's very good at photos that get picked up. I know that's what I'm up against and that's part of it. But it's an opportunity, too. I can introduce myself to Canadians on my terms and put forward what I believe will captivate some imagination and resonate with people.

"I am a very positive person and I'm aware of the challenges. I'm going to put everything I have into this."

Roy MacGregor is a feature writer at The Globe and Mail.

THE NEW CONSERVATIVES: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL