What if Toronto had a massive park ready to be born? A 480-acre green space on the edge of downtown with dramatic topography, a rich mix of plant and animal life and deep links to the history of Toronto?

It does: the lower part of the Don Valley. And after a century of neglecting and abusing that space, it is time for Torontonians to bring it back.

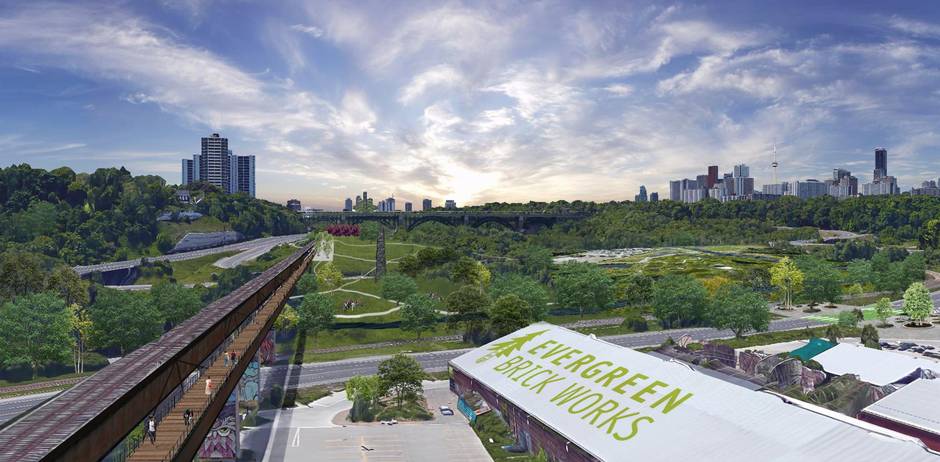

City officials and Evergreen, a non-profit group, have been working for months on an ambitious goal to transform a stretch of the valley, from Pottery Road down to Front Street near the river’s mouth, into a massive park.

You probably don’t know that landscape well. Most Torontonians don’t. We’ve seen it through car windows on the Valley Parkway, from the Bloor Street subway, from the windows of a GO train – but rarely from within. Though the upper Don Valley is relatively green and well used by locals, this part has been a dumping ground, a waste sink and a transportation corridor for more than a century. The potential for regeneration is awesome. But we have to learn how to see it.

To help that process, Evergreen brought together landscape architects and other professionals for a design charette in October. During a rainy two days at the Brickworks, a consensus emerged: that with better access and changes to the infrastructure in the valley, the city could gain a tremendous public space, insurance against the effects of climate change and a healthier river valley.

Perched over a large map of the area, landscape architect Claude Cormier laid down a piece of tracing paper and pulled out a red marker. “This is Central Park,” he explained, sketching a rectangle that represented about 800 acres. “It’s not so far in scale, and it is a park with an urban edge. So is this valley.”

In another room, landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh was making the argument for a valley park. “The site is a lovely leftover,” he said. “A hundred years ago, we wouldn’t have chosen it to be a park – you would have chosen something more perfect. But it’s incredible: Its centrality, and the fact the city is tied to the ravines.”

The city and Don have had a fraught relationship. John Graves Simcoe, lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, chose a spot not far from the Don’s mouth to found York in 1793, and saw the river, known to the Ojibwa as Wonscotanach, as a pastoral place: He and Elizabeth Simcoe built a house they called Castle Frank in the wilds of what is now Cabbagetown.

But the river wound up mostly as “a sink for industrial wastes” and raw sewage, as historian Jennifer L. Bonnell wrote in her 2014 book Reclaiming the Don. It was “a marginal space” – its banks filled in with noxious industries, its lower reaches built into a channel in an “improvement project” of the 1880s. It was seen as cheap available land for railways and later the Don Valley Parkway. The land was cut and reshaped, the river polluted with salt, industrial runoff and human waste.

Until the 1960s, people did use the valley for recreation, swimming in the murky river, skating and playing in Riverdale Park, communing with nature.

Healing this section of the river has been an active dream since the 1980s. A citizens group launched the Task Force to Bring Back the Don in 1989, and the old City of Toronto picked up on its efforts. They helped create Waterfront Toronto and its plans for the river.

Among the movement’s leaders was ecologist and landscape architect Michael Hough, who argued for the importance of nature within the city – for reasons of ecology and for the well-being of its citizens. He believed there are two kinds of nature in cities: the “pedigree” variety of lawns and flowerbeds, and the “fortuitous” kind that emerges despite our efforts, “found everywhere in the forgotten places of the city.” The lower Don Valley is such a place.

How to bring it back to our attention? Evergreen has begun to do this with the Brickworks – with a sophisticated mix of programming, education and place-making that would have been politically impossible for the city to do itself. Now, Evergreen is helping lead the valley conversation and seeking donors to help fund the design and study of the park.

A few small moves would get it in motion. Proponents envision new bike lanes on Bayview Avenue that would make it less terrifying to go there on two wheels. An old rail trestle would become a pedestrian bridge. New bridges, stairs and paths would welcome people from Cabbagetown and from Regent Park, from Corktown and the emerging neighbourhoods in and around the Port Lands.

But in the longer term, the plan would mean combining two rail corridors, both controlled by Metrolinx, reconfiguring the DVP ramp to Bloor-Bayview and removing a city works yard that now sits in the middle of the valley. But governments are budgeting at least $1-billion for roads, water, parks and rail improvements in this zone, including the electrification of GO’s train lines and the Gardiner Expressway rebuild. The river is unruly, prone to powerful floods; a thoughtful, coherent landscape would mitigate the risks for infrastructure and serve the environment of the valley.

At the charette, urban designer George Dark put it this way: “From time to time, we lay waste to the valley to accomplish things – the DVP, for example. And in our lifetimes, we will do this again.

“This is how the next big public works project in the valley – and it will come! – can remake it.”

It’s an enormously bold vision, and this is the right moment to move it forward. It’s in line with a set of projects in cities around the world that repurpose old infrastructure to serve the 21st-century city, like New York’s High Line and Chicago’s The 606. (The panel Thursday included Beth White, who helped create The 606 bike trail on a rail line in Chicago.) It follows local projects including the Under Gardiner, the adjacent Corktown Common, and work planned nearby to “renaturalize” the mouth of the Don River.

The latter would be one of the biggest infrastructure projects in Toronto’s history, and it represents a new idea of city-building: As Mr. Van Valkenburgh’s firm wrote in its competition-winning entry for that site, “recycling the industrial past” into a “sustainable green city.” The Don Valley River Park would be the next step in that transition.

The city is signalling its support. “We need to plan for new ways to connect people with our rivers and ravines,” Mayor John Tory wrote in an e-mail.

“The opportunity to revitalize this part of the Don River Valley is a great first step in re-engaging with the river. This is a terrific opportunity for the city to demonstrate our leadership in creating amazing open spaces, reclaiming natural places, and addressing the reality of extreme weather occurrences.”

In its 1991 report, the Task Force to Bring Back the Don wrote: “The opportunity is there to bring the Don back all the way. The key is to starting thinking of the Don as a place in itself.”

Now, after a long period of neglect, it is time to do just that. The river has shaped the city; it could do so again. As Mr. Van Valkenburgh put it: “How different will Toronto be in 100 years, if it doesn’t seize the opportunity?”

To learn more about the project, you can attend The Don Dialogues: The Don River Valley Park on April 21 at 7 p.m. at Evergreen Brickworks (550 Bayview Ave). Registration is free at evergreen.ca.