In Etobicoke on Friday, July 29 City of Toronto arborists perform maintenance to a tree by cutting off dead and dangerously hanging tree limbs and branches in an effort to increase the tree’s lifespan and reduce the hazard of falling and dead branches. The branches, limbs and leaves are then processed through a large woodchipper, and the site is cleaned.

Christopher Katsarov for The Globe and Mail

When Todd Irvine walks through Toronto's extensive ravine system – one of largest in the world for a city – he notices things most people don't. A trained arborist, he sees the ribbons of original forest threading the slopes.

"If people really understood what those were, they'd be like, 'Holy crap,'" Mr. Irvine says of the oak-hickory woods, one of the last glimpses of the area's native forests. Now, the forests are being overrun by an invasive species. "To let Norway maples go in and kill those trees, it's devastating," he says.

Toronto's urban forest is in trouble. Climate change is set to have a major impact and planners must scramble to temper the fast growth of invasive species. As the city tries to expand its canopy, mistakes from the past are showing why tree choice and smart planning matter for the coming years.

Cities are already a hostile place for trees to grow. The "heat island" effect creates a climate too warm for comfort, salt from the winter is damaging, the soil is suffering from nutrient degradation and root systems often go into shock.

Finding trees that are resilient is a priority for Toronto. Already accustomed to the ecosystem and climate, native species often possess the hardiness required to endure the urban environment.

"This is why we're developing species diversity. Native trees will generally have the strongest ability to survive because they're unique to that area," says Jason Doyle, Toronto's director of urban forestry. "But things are starting to change."

Strong winds, heavy rain, drought, heat and extreme cold are likely to arise with greater frequency, Mr. Doyle says, and the native environment that trees are used to is slowly changing beyond recognition.

"In an urban centre, we've disturbed things so greatly that it's much harder to just put native trees in the backyard and expect them to perform well because they did 150 years ago," says Mr. Irvine, an arborist at Bruce Tree Expert Co. Ltd. "It's not about, 'Oh, if we just pick the right trees and plant them in the right diversity, we'll all be fine.' No way. Drought will kill all trees."

The problem is for city planners is that there is no "miracle tree."

"Something that is resilient to drought is less resilient to wind storms," Mr. Doyle says. "So you have to have this balance. You put [in] something that is strong and sturdy, but it's not resilient to drought."

Planners experimented with what seemed like miracle trees in the past, with checkered results.

Cities began to plant trees on streets starting in the early 1900s, although officials lacked training in forestry practices, says Michael Rosen, president of Tree Canada, a non-profit group that advises communities, governments and business on urban tree planting and growing strategies.

MURAT YUKSELIR/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

"Trees were very much regarded as almost on par with a fire hydrant or a lamppost or a watering trough or something like that. They were just something to sort of install into the city so the amount of thought that went into species composition was fairly limited," he says.

Cities chose a narrow range of trees, with many in Eastern North America relying heavily on elms, which seemed like the ideal urban species.

In the early 20th century, Toronto was filled with "cathedral streetscapes," so called for the branches of elms on either side of the street that met in the middle, forming a vaulted canopy of foliage.

In the late 1960s, the blight of Dutch elm disease first crept into Ontario, having already devastated the elm population south of the border. Death came swiftly for the millions of infected trees. Carried by beetles, the fungus choked the vascular system of elms, leaving behind its signature winding, venous burrows inside the trunk. In the end, it destroyed 80 per cent of Toronto's elm population.

"In a course of one or two years, you'd have whole subdivisions that would go from this beautiful cathedral of trees and protection to gone," Mr. Irvine says. "Gone. Nothing. Zero."

Toronto then began its search for a new tree to repopulate the streetcar suburbs.

It was ash trees that were shown to have promise – a sturdy, resilient tree that thrives in an urban setting.

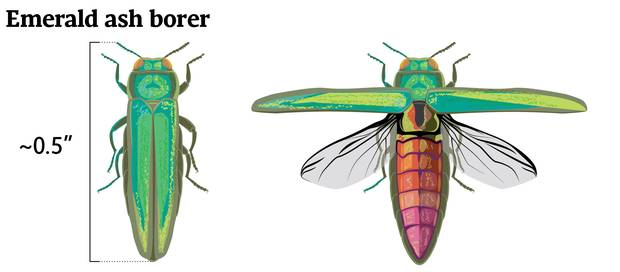

But in a bitter irony, the emerald ash borer beetle was reported in the Greater Toronto Area in 2007 and soon began feasting on the trunks of the region's ash trees.

"I think they just thought, 'Oh, what a fluky thing.' Human memory can be kind of short. I think at the time, it was like, 'Oh well, we blew that one. What a horrible disease that is. Here, let's try ash. Nothing affects it,'" Mr. Rosen says. "And at the time, it was true. There was nothing that really affected it."

MURAT YUKSELIR/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Despite the city's best effort to hold the beetle back, current estimates suggest that it will kill off 3.2 million ash trees in the GTA.

Planners saw also maples as another remedy to fill empty streets. The trees were fast-growing, strong and iconic. Flourishing in the degraded soil of an urban environment, the silver and Norway maples seemed the ideal shade trees for cities.

But when roots of maple saplings are trimmed for transportation, they have a tendency to regrow perpendicular to the cut. The shallow root systems then wrap around the trunk, tightening their grip and eventually strangling the tree. In this process, called girdling, the desperate tree will grow brittle, starved of nutrients. The tenuous hold maples have over their limbs is weakened and branches drop with much higher frequency, often without warning.

The Norway maple is now the most common tree in the city, with a population exceeding 660,000. Because of the trees' invasive nature, weak limbs and girdling roots, the urban forestry division has stopped planting new ones.

"The reality is, they provided an incredible canopy cover and served their purpose very well," Mr. Irvine says. "And now we look back and think, 'Wasn't it dumb we planted all these?' Well, thank God we did in some ways, because they did so well for so long."

In spite of past challenges with tree choice, the city is determined to increase the urban canopy.

Big, leafy trees with expansive crowns provide the most benefit to the canopy, keeping buildings cooler in the summer, lowering energy costs and cleaning the air.

The city's original urban forestry service plan called for canopy expansion to be completed by 2050, but financial constraints have delayed it until 2057.

Even so, Mr. Doyle says the city has planted well over 700,000 trees since 2007.

Most of Toronto's trees are small, with an average trunk diameter of 16.3 centimetres, much smaller than the recommended 75 cm. Larger trunks can absorb significantly more air pollution and provide more leaf cover, according to the city.

Part of the problem facing cities now looking to diversify their urban forests is that they have become so developed that there is not a lot of room for new trees to grow. New street trees often struggle because they are planted in compacted soil surrounded by paved surfaces that stymie water absorption.

"It's much harder to grow a tree in an urban landscape now than it was. … You can't be as haphazard and lackadaisical with your tree planting because they're not going to survive," says Mr. Irvine.

But new plantings alone will not get Toronto to its lofty 40-per-cent canopy target, says Janet McKay, executive director of Toronto-based non-profit LEAF, which stands for Local Enhancement and Appreciation of Forests.

The west looking view from Riverdale Park East offers the Toronto skyline beyond the trees of the Don Valley and Riverdale Park West on Aug. 7, 2014.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Ms. McKay says the city should do more to preserve its large mature trees, which also provide the most benefits instead of focusing on planting smaller trees. "They're never going to reach the size and health of our mature trees that we have now," she says.

To blunt the spread of invasive trees and improve the strength of the canopy, arborists recommend a number of strategies.

Municipalities are hoping to adapt to a warming climate by experimenting with 'range trees'– the process of slightly pushing the native range of a tree species. The Kentucky coffeetree, native to Southern Ontario and the Midwest, has been successfully grown in the York Region.

In partnership with Forests Ontario, cities are also using local seeds from native trees to increase the genetic diversity of the forest. Most of the trees planted in Toronto are genetic clones, or cultivars, city staff say.

"As cloned trees are genetically identical, stands of clones are highly vulnerable to threats from insects, disease or the impacts of climate change," Brian Mercer, a manager in the city's forestry department, says in an e-mail.

To combat this uniformity, the aim is to create a seed bank, drawn from genetically diverse native trees, making the canopy more resilient to the looming threats of infestation and harsh weather. In 2016, the city hopes to plant 2,000 trees using this program.

"In some ways, I think it's the most terrifying time for urban forests because with emerald ash borer, more insects will be coming. Climate change is going to wreak havoc on our forests and development is wreaking havoc on our forests," Mr. Irvine says. "But it's also kind of exciting, because crisis always bears innovation."