Who is a street for? For people in cars, or for everyone?

That's the question at the heart of the City of Toronto project to remake King Street. The three options for the bold pilot project, revealed at a packed public meeting this week, would each give priority to streetcars and pedestrians at the expense of private vehicles.

Each would save untold hours for the 65,000 people who crawl along on the King streetcar each weekday; each would shift some of the space along the street from its current arrangement, in which the 16 per cent of users in cars occupy 64 per cent of the space. Any of these schemes would make King Street safer. They make sense.

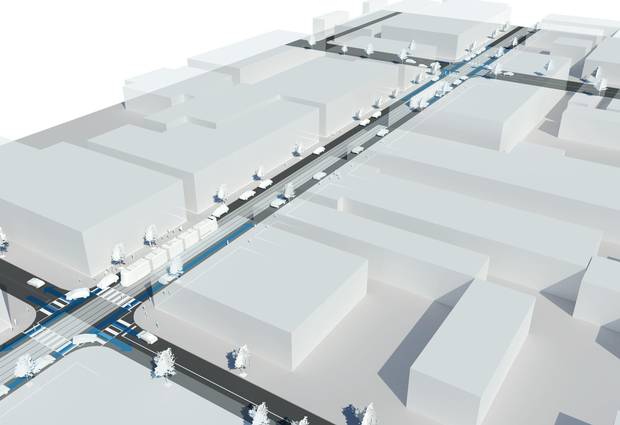

Option A - Separate Lanes.

So get ready for an endless opera of complaint. Whether City Council can tough out the inevitable car-centric whining, and defend a more just and sensible approach to the streets, will be an important indicator for the future of the city.

In Toronto, it's not traditional to think about road users as equals. The primacy of the car is still unquestioned in city politics. Just look at the recent decision, championed by Mayor John Tory, to spend nearly an extra $1-billion to rebuild the eastern Gardiner as an expressway, to save a few minutes a day for 3 per cent of downtown commuters. You could add a lot of transit service for that kind of money.

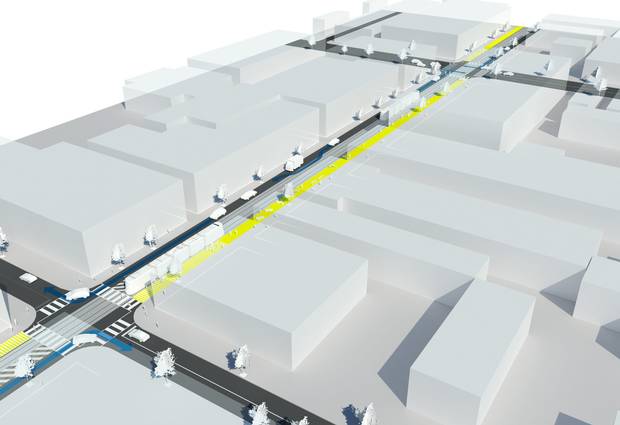

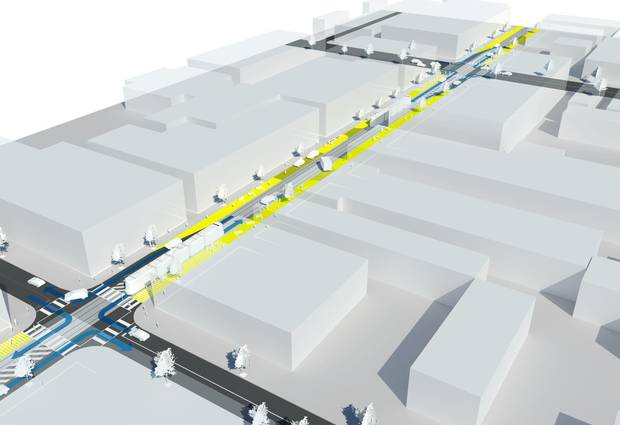

But the King pilot project – which will be planned through the springtime, with an eye to a fall rollout – isn't much about money; it's about shifting the use of a resource we have, road space, to put the focus on transit. That will mean making it harder for private cars to use King; in two of the three proposals, dubbed "Alternating Loops" and "Transit Promenade," it wouldn't be possible to drive continuously along the central part of King Street at all, but only around each block to reach specific destinations. Through car traffic would be relegated to other cross-streets, most closely Front, Wellington, Adelaide and Richmond. This is no "war on the car."

Option B - Alternating Loops.

Instead, planners are proposing a modest tradeoff. Sixty-five thousand people ride the 504 streetcar on a normal weekday, and data shared by the city suggests that streetcars slow down to six kilometres an hour in the morning rush hour, and as slow as five kilometres an hour in the evening. That's slower than a moderate strolling pace. It is literally faster to walk.

Many thousands of Torontonians can confirm that riding the 504 in rush hour is preposterously frustrating. This is exactly the kind of endless delay that induces road rage among drivers. On the streetcar, people seethe quietly, or just sigh.

Helping them – moving more people more quickly – is one of the goals here, and that's laudable. More reliable transit will lure some people out of their cars. More than that, it acknowledges that commuting time for people on the streetcar, heading to the largest concentration of jobs in the region, is just important as for those in cars. That is news.

Option C - Transit Promenade.

But city staff also suggest two other goals, to support economic prosperity and improve placemaking. The best local precedent is DTAH and West 8's highly successful revamp of Queen's Quay, which began as a pilot project. It clearly showed the benefit of emphasizing transit and walking: you make places that are better to spend time in. The outlook recognizes that streets are destinations, as well as thoroughfares, large stretches of public space that can be used for all sorts of purposes. Two of three King proposals would bring wider sidewalks and a more robust public realm.

To that end, the initial ideas floated this week identified different characters along different stretches of King: massive density and a lack of public realm between Bathurst and Spadina, a "big public realm move" in the Entertainment District and so on. An expansion of David Pecaut Square in particular has the potential to be transformative.

It's all about, as city planners put it, listening to the street. I recently heard this idea expressed by the landscape architect Adam Nicklin, whose firm PUBLIC WORK is part of the team on this project and also a comprehensive study of downtown's public spaces. For decades, he said, street design has been driven by engineering and its standardizing mindset: one-size-fits-all formulas have shaped our roads and sidewalks, without regard to the specifics of the places they run through. Why not bring some critical thinking? Why not let streets be shaped by the blocks and the neighbourhoods they run through?

And why not let them serve everybody, fairly and efficiently? That's the vision that needs to be defended. As the pilot proceeds, we'll learn whether 21st-century Toronto is ready to make room for everybody, even on the road.