Abby Fedosoff was a smart, active and sociable teen. A competitive swimmer, she loved writing, watching Friday night football games and listening to music, especially One Direction. She got good grades and would have graduated this spring.

Two years ago, on an April night, Abby slipped out of the house and took a bus to a west-end Toronto subway station. The last thing the 15-year-old searched on her phone was how late the trains ran. It was nearly 1 o'clock in the morning as she left the platform and walked into the tunnel.

"When it happened we were sound asleep. We had no idea she had left home until the police came," said her mother, Jen Fedosoff, who remembers telling the officers that Abby was in bed. "Her door was closed but she wasn't there."

Only after reading some of Abby's private writing did her parents realize she'd been in pain and felt unable to ask for help.

A photo of Abby Fedosoff sent by her family

Ms. Fedosoff is haunted by how it could have turned out differently. What if they'd heard her trying to leave? What if the bus driver had thought it odd enough to intervene when a young girl boarded in her slippers in the middle of the night? What if the Toronto Transit Commission had made it harder to access the tracks?

"It's been 27 months to the day since she died and nothing has changed," Ms. Fedosoff said in an interview earlier this summer.

Jennifer Fedosoff, whose teenage daughter Abby committed suicide, poses for a picture at her home in Toronto, Thursday July 20, 2017.

Mark Blinch/Globe and Mail

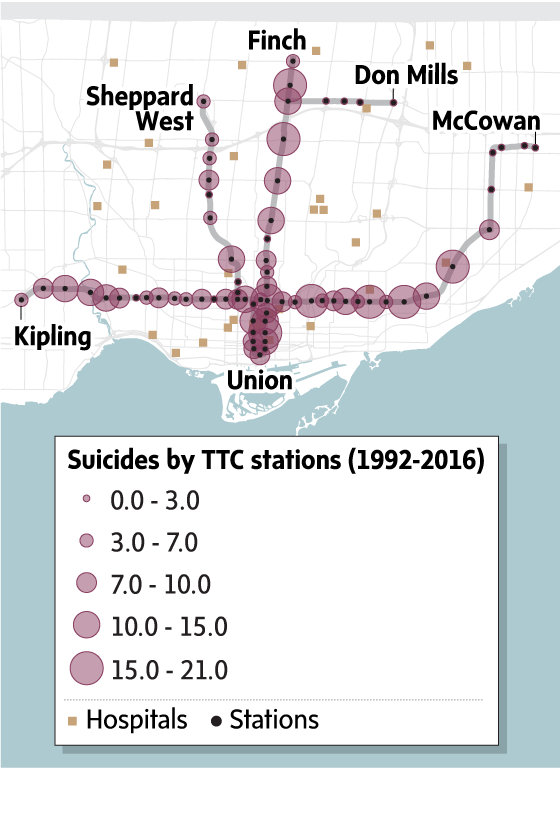

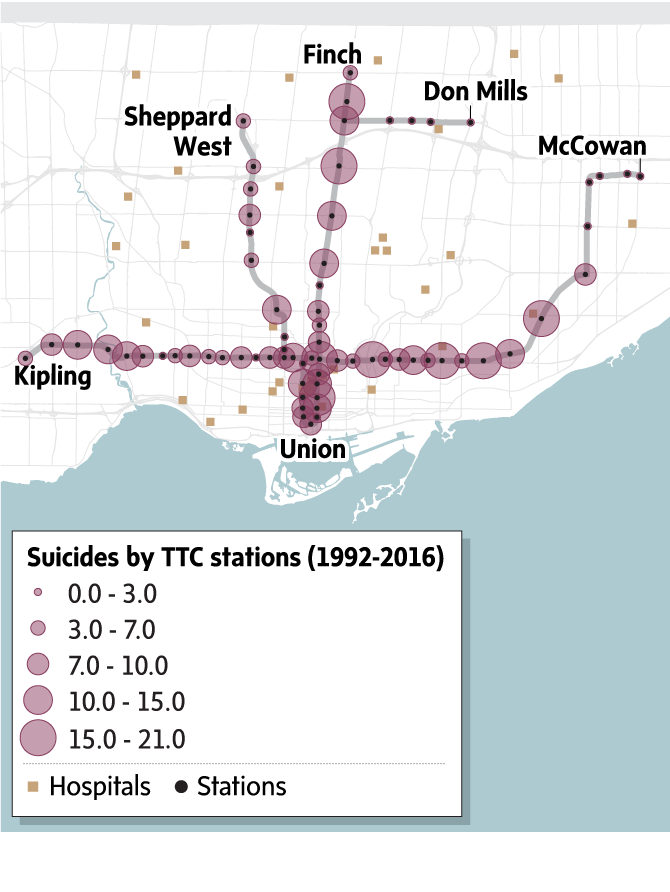

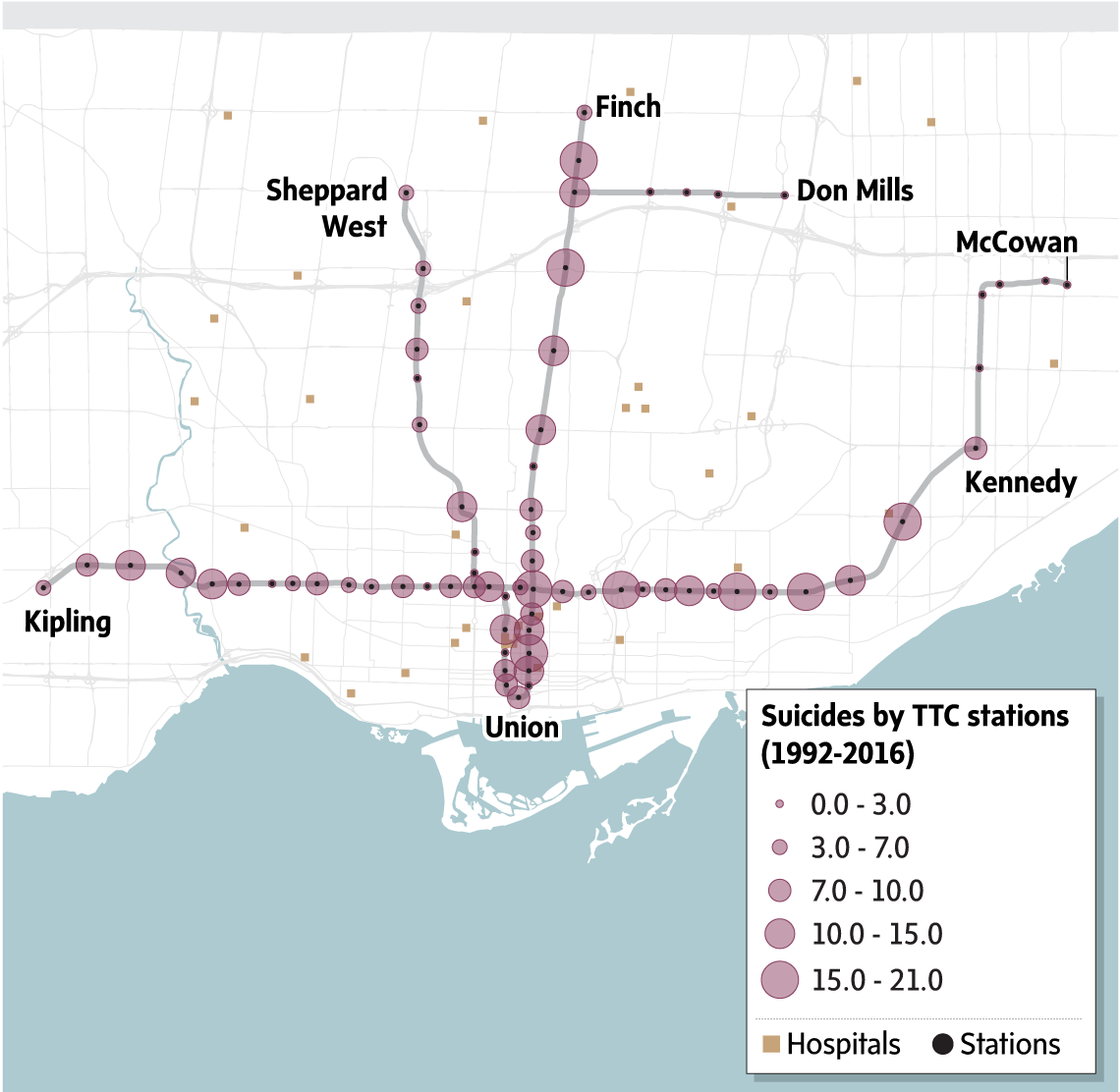

The subway station where Abby chose to end her life is one of the worst in the city for suicidal acts. The TTC has always said there are no suicide hot-spots, but acknowledge having done limited analysis of their data. The Globe and Mail study of decades of agency data, obtained for the first time after a lengthy freedom of information process, found long-term patterns showing that these incidents are distributed very unevenly throughout the system. Some stations are far worse than others.

At two TTC stations, no one has ever tried to die by suicide. At the other end of the spectrum, Queen, Ossington and College have had more than 50 people try to do so since the stations opened in the 1950s and '60s. Dundas has emerged as the worst station over the last quarter-century. In some cases, stark discrepancies exist within a single station. At the Spadina subway interchange, 39 people have sought to kill themselves on the Bloor-Danforth line, but only one has tried on the Yonge line.

Over all, the Bloor-Danforth line has more suicides than the Yonge line, in spite of carrying fewer passengers. When adjusted for ridership, the gap between the two lines grows wider, and has become increasingly pronounced in recent decades. The Bloor line is getting worse.

Rahel Eynan, an adjunct assistant professor at the Lawson Health Research Institute in London whose 2011 University of Toronto dissertation examined suicide prevention on the TTC, said studies suggest stations with higher rates of suicide are often more heavily used or near mental health facilities. Other factors include the frequency of trains and socio-economic or demographic factors in the area nearby.

But research on the issue has been contradictory and observers caution the reasons may vary by station and city, which makes prevention a challenge.

"There's no way of proving there's anything particularly attractive about any particular station," said Dr. Brian Mishara, a psychology professor at the University of Quebec at Montreal and founder of the Centre for Research and Intervention on Suicide and Euthanasia.

These trends raise the question of whether some stations should be prioritized for interventions, a targeted suicide prevention strategy being done elsewhere in the world. TTC officials – who concede that they do not know why some stations have a higher incidence and argue there are no significant trends – are currently focused on system-wide solutions. A decision on platform barriers has been pushed back by at least a year, though, with the agency deciding to commission a new report on the option.

MICHAEL PEREIRA AND MURAT YUKSELIR /

THE GLOBE AND MAIL SOURCE: TTC; TORONTO OPEN DATA

MICHAEL PEREIRA AND MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE:TORONTO TRANSIT COMMISSION; TORONTO OPEN DATA

MICHAEL PEREIRA AND MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL

SOURCE:TORONTO TRANSIT COMMISSION; TORONTO OPEN DATA

The Problem

More than 1,400 suicides and attempts have taken place in the Toronto subway since it opened in 1954.

The TTC has long kept quiet with most details about these incidents. It has been opening up a bit in recent years – the agency's official Twitter account acknowledges when subway closings are related to a "personal injury at track level" – but has historically refused to release comprehensive information about where these have happened.

The Globe and Mail obtained the data after the TTC initially fought and then eventually abandoned its opposition to releasing this information under access laws.

The TTC's data show no obvious links tying together the worst stations, though. Dr. Eynan said that it is most likely that people are being attracted to these "different stations for different reasons."

"It's difficult to draw conclusions about what drove them to [suicide], and especially what drove them to specific stations," she said.

Complicating this, the worst stations over the last quarter-century are very different. They include a high-ridership station in a dense downtown neighbourhood, less-used stations in the eastern inner suburbs and one in a well-heeled part of north Toronto that has relatively few people living nearby.

Dr. Mark Sinyor, a psychiatrist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre who has worked with the TTC on its anti-suicide efforts, did not want to speculate on why these particular stations attract more suicidal people. But he said the fact that the worst of them are so different "just illustrates the difficulty of suicide prevention."

The Globe looked most closely at the time from 1992 through 2016, the period which had the best data and during which the city and its subway system looked more or less the way they do now. During that time, 493 people sought to kill themselves in the subway, one-third of them choosing 10 of the system's 74 stations.

According to TTC chief safety officer John O'Grady, the agency doesn't normally take this sort of long view. It looks at five-year periods when checking for problem areas, he explained, adding that each time staff did that they would find different results.

"So we'd say, well, what if we had done something? It would've been in the wrong place," he said.

Over the longer period, some patterns emerge.

Although the two stations closest to the Bloor viaduct skew higher than average, there was no uptick in suicide incidents at them in the decade after the safety barrier was erected on the bridge, compared with the decade before. This finding buttresses research showing that suicidal people who are deterred by a preventative measure do not simply choose another way.

It also appears the TTC's Crisis Link program – which features subway advertising and phones connecting distressed people to counsellors – may be having an impact. The number of suicide incidents dropped about 8 per cent in the five years after the program began, compared with the five years before.

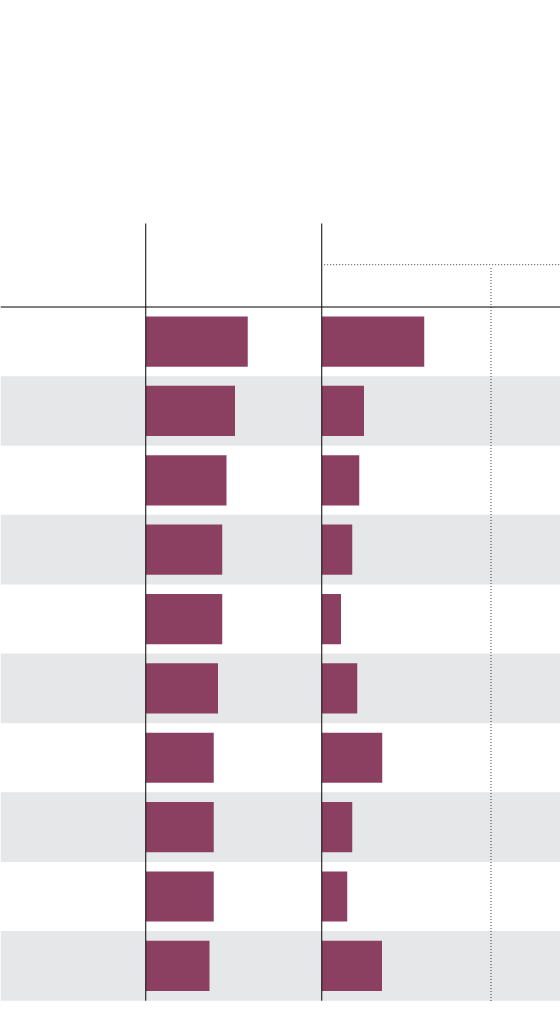

The Globe's analysis also shows several locations stand out for having a large share of the suicidal acts. Thirteen of the 74 stations were at least twice the average.

Despite having roughly the same number of stations as the Yonge line, the Bloor-Danforth line has had considerably more suicides and attempts. But the single worst station of the last 25 years was on the Yonge line, where Dundas had more than three times the incidents that might have been expected if they were averaged across all stations.

In spite of this high relative incidence, the TTC's Mr. O'Grady argues that suicides would still be rare enough at that station to be very hard to stop.

"If it's going to happen once a year, what can we really reasonably do?" he said. "Even if you staffed it, how many staff would it take? You'd have to be on both platforms, you'd have to be from 6 in the morning to 11 at night and what if [the staff member] wasn't in the right place? I mean, it's just. I just couldn't. I don't think I could see my way through to do the business case."

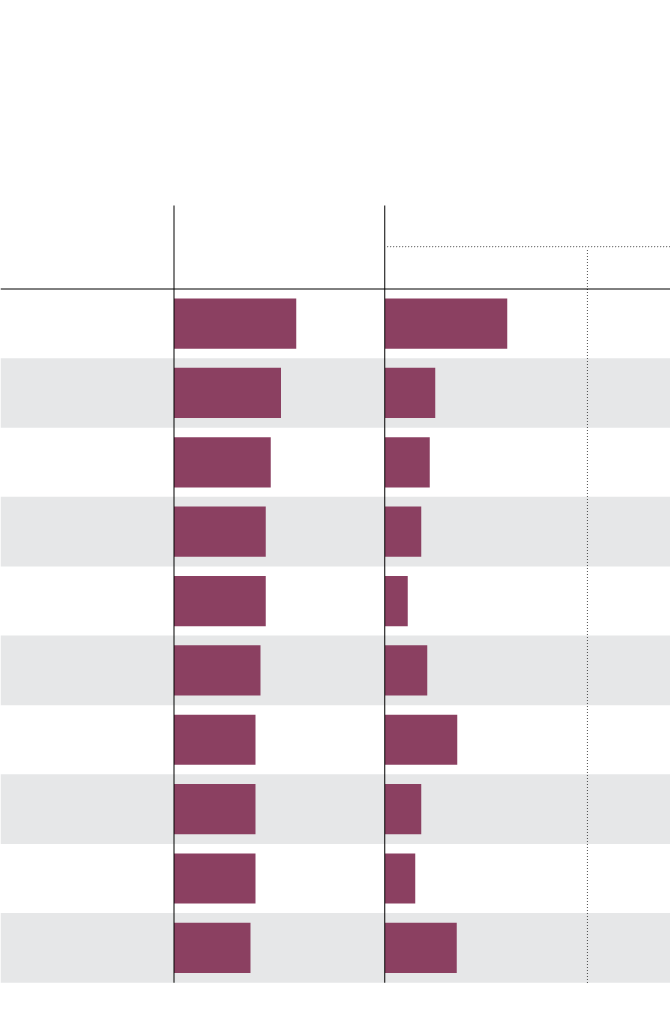

Many of the stations with the highest

number of suicides have middle-to-low

weekday ridership

Of the ten subway stations where suicides have

occurred most frequently since 1991, seven

don’t even register in the top 20 for ridership

Station

Suicides

per year

Ridership (2015)

Thousands

Rank

Dundas

0.94

81.3

7

Broadview

0.83

33.5

24

Warden

0.75

29.7

30

Main Street

0.71

24.1

41

Coxwell

0.71

15.3

53

York Mills

0.67

28.2

34

Queen

0.63

48.0

15

North York

Centre

0.63

24.2

40

Royal York

0.63

20.2

45

College

0.59

47.8

16

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: TTC

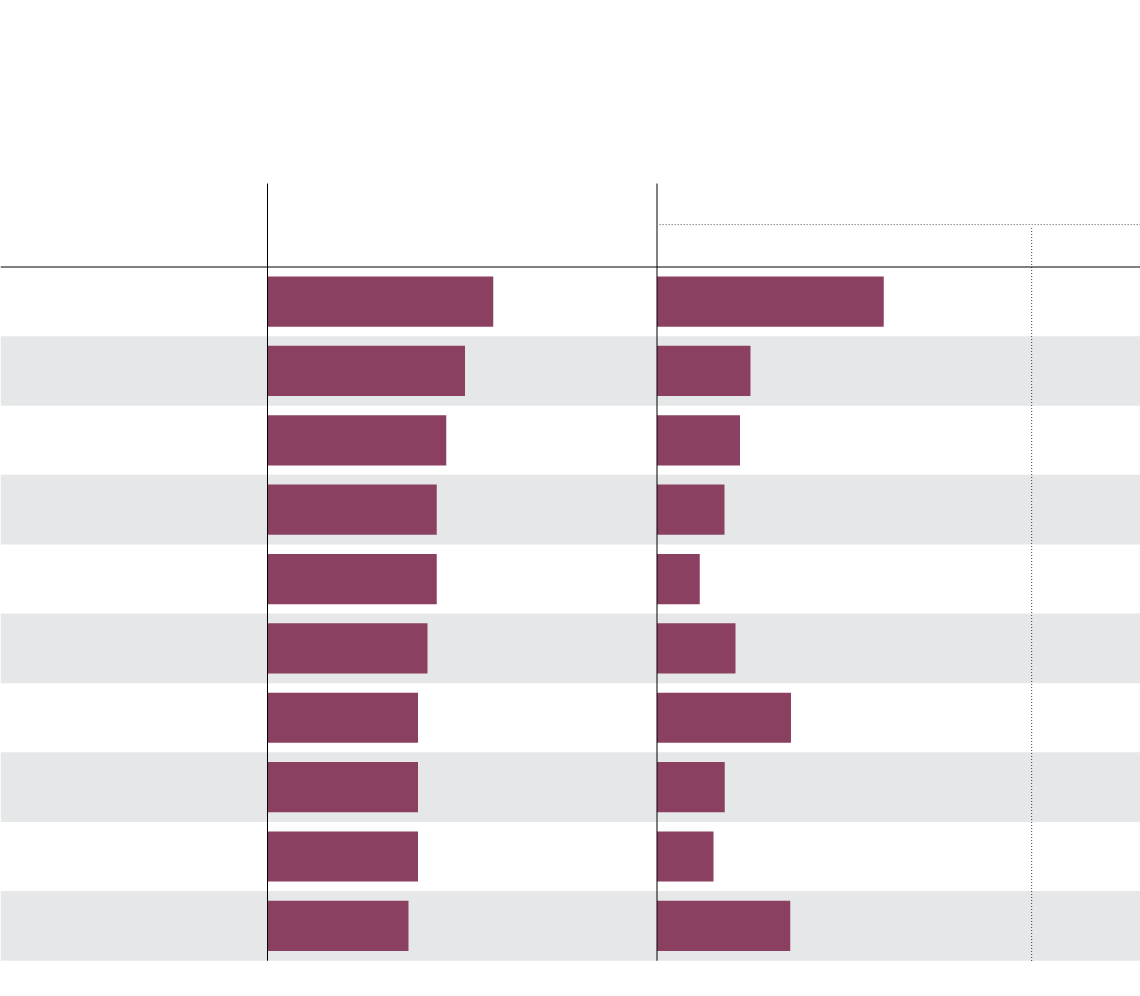

Many of the stations with the highest number of

suicides have middle-to-low weekday ridership

Of the ten subway stations where suicides have occurred

most frequently since 1991, seven don’t even register in

the top 20 for ridership

Station

Suicides

per year

Ridership (2015)

Thousands

Rank

Dundas

0.94

81.3

7

Broadview

0.83

33.5

24

Warden

0.75

29.7

30

Main Street

0.71

24.1

41

Coxwell

0.71

15.3

53

York Mills

0.67

28.2

34

Queen

0.63

48.0

15

North York

Centre

0.63

24.2

40

Royal York

0.63

20.2

45

College

0.59

47.8

16

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: TTC

Many of the stations with the highest number of

suicides have middle-to-low weekday ridership

Of the ten subway stations where suicides have occurred most frequently

since 1991, seven don’t even register in the top 20 for ridership

Station

Suicides per year

Ridership (2015)

Thousands

Rank

Dundas

81.3

7

0.94

Broadview

33.5

24

0.83

Warden

29.7

30

0.75

Main Street

24.1

41

0.71

Coxwell

15.3

53

0.71

York Mills

28.2

34

0.67

Queen

48.0

15

0.63

North York Centre

24.2

40

0.63

Royal York

20.2

45

0.63

College

47.8

16

0.59

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: TTC

How to stop it

Toronto has averaged about 213 suicides per year across the city for the two decades through 2013, the most recent data available from Statistics Canada. During that same period, TTC data show, an average of 23 people each year chose the subway system as the way to try to end their lives.

The overall suicide rate in Toronto has generally lagged Vancouver during that two-decade period, though the cities are converging. Montreal, which has historically had a higher suicide rate, is dropping down to the same level. But The Globe's analysis indicates that Toronto's transit agency has a disproportionate amount of suicides, when adjusted for ridership, making this a key issue for the TTC and the city to tackle.

Dr. Eynan said one tactic can be as simple as putting on more staff at the worst stations, to increase the number of people keeping watch for unusual behaviour.

Abby's mother agrees. "If people knew that [the one my daughter used] was a problem station, maybe people would look out more," Ms. Fedosoff said. "I hope the TTC is training their staff to be more vigilant in that station."

Other cities offer further examples of how to bring in targeted anti-suicide interventions. Some have instituted measures at certain hot-spot stations or on specific lines, with the effect of reducing the number of fatalities instead of just moving them elsewhere.

A number of transit agencies have installed pressure pads or other detectors to reveal when someone has gone down to the track. This wouldn't stop people who jump, but could save those who enter tunnels.

Some cities in Asia have experimented with blue lights in stations. These seem to reduce the number of suicides, at least initially, with researchers speculating this may be because the colour is calming or because it makes people think of the police. At one particularly high-incidence Tokyo station, transit officials have been deploying a range of measures, including soothing lights, volunteer patrols and large-scale photos of magnificent natural scenes. Data about the results are not yet available.

The London Underground has drainage ditches in some of its stations. These have become a de facto suicide reduction technique, with more people surviving attempts at the stations that have this feature. The ditches create space around the train, making it less likely someone will be fatally struck, and offer more room for someone who has a change of heart to duck for cover.

Research on survivors of transit suicide attempts shows they choose the method in part because they incorrectly assume it to be a sure thing. In Toronto, though, about half of people attempting suicide in the subway do not die in the act. Dr. Mishara said that one way to reduce the appeal of transit suicide is for the public to understand that its reality does not match the common perception.

"Those that do die don't necessarily die painlessly, or on the spot," he stressed. "Those who do survive being hit by a train often have horrendous injuries."

Dr. Sinyor, the Sunnybrook psychiatrist who has worked with the TTC on its anti-suicide efforts, said that "most people who are suicidal don't necessarily want to die, they want to remove themselves from intolerable pain." What they need to know is that the city has "very, very good treatments for people who are depressed, as well as [for] all sorts of other mental health problems that contribute to suicide."

According to multiple experts, the single most effective way to prevent transit suicide is by installing platform-edge barriers to separate passengers from the tracks. This is the solution the TTC is focused on and the agency has been mulling it for years, though the prospect recently hit another roadblock.

TTC chief operating officer Mike Palmer said that that most recent draft of a consultants' report – which pegged the cost per station at $24-million – was not up to the required standard. He's not confident in the cost estimate, but unsure whether it may be too high or too low. He decided to hit pause on the concept.

"I think what we're doing at the moment is we're trying to decide what to do next," Mr. Palmer said. "I think before we can move forward we just have to stop. In trying to do the right thing, we need to make sure we're doing the right thing the right way."

As well as preventing suicide, these barriers would help service reliability by reducing other delays, including garbage fires on the track and trespassers going down from the platform. But installing them is a complicated project costing a lot of money the agency does not currently have. Some at the TTC advocate for them on new stations, but are more hesitant about retrofitting current stations, while others say the human and social cost of suicide justifies the expense.

"I think it is not for the TTC to make the final decision," Mr. Palmer said. "I think it's the community, the medical experts, the board, the mayor, our funders, as to whether the expense and the time it will take to do is worth it morally or monetarily or efficiency wise."

With graphics and data reporting by Michael Pereira and Murat Yukselir