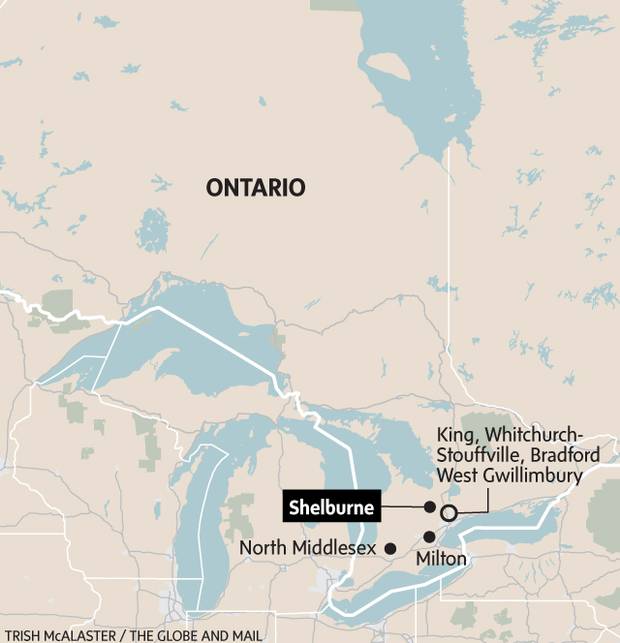

The soaring new office and condominium towers of downtown Toronto have come to stand for the dynamism of Canada's biggest city. But if you really want to understand the staggering growth of greater Toronto, don't look up, look out – way, way out. Look at what is happening to tiny Shelburne, fully 100 kilometres from the city centre.

For generations, this was a sleepy farming community where everybody knew everyone. Farmers would drive their cattle down the muddy main street to board trains to Toronto slaughterhouses. Motorists on the road to the ski chalets of Collingwood or the beaches of Lake Huron would pass by with hardly a second thought.

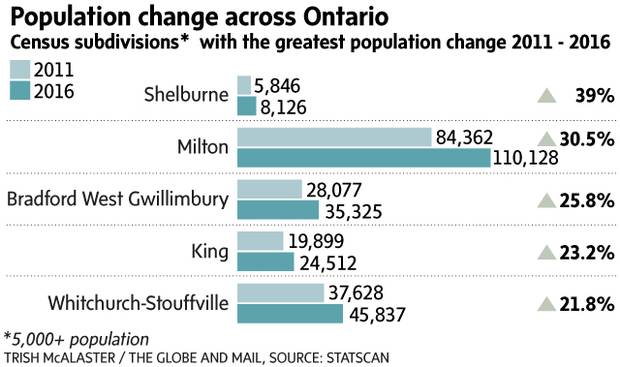

Today, little Shelburne is the second-fastest-growing town in all of Canada.

New census figures show it grew 39 per cent between 2011 and 2016, second only to Blackfalds, Alta., near Red Deer, among municipalities with a population of at least 5,000 and located outside a major metropolitan area.

People from down the road are flocking to Shelburne (its official slogan: "A people place, a change of pace") to take advantage of the fresh air, open spaces and house prices that are still in the realm of sanity. Some commute all the way to downtown Toronto and back, an odyssey that can take five hours, round trip.

Many drive the 45 minutes to Brampton, the booming edge city that is now too crowded or expensive for their tastes. Shelburne is becoming a bedroom community – and an attic bedroom at that. Toronto is so big now that even its suburbs have suburbs.

That an obscure town far from Toronto's old orbit can undergo such a boom is telling. It underlines the explosive growth of the city, which overtook Chicago in 2013 to become the fourth-largest in North America after Mexico City, New York and Los Angeles. About 10,000 new residents move into the downtown every year, filling the skyline's glass spires.

If the migration continues, the downtown population could double by 2041, reaching 475,000.

The view approaching downtown Shelburne from westbound Highway 89.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

That's good news for the city, which is enjoying a burst of downtown vitality, but it's only part of the story. The lion's share of the growth is taking place outside the core. A 2013 study found that two-thirds of Canadians live in suburbs. In big urban regions such as greater Toronto, it discovered, there is five times as much growth on the edges than in the centre. One of the study's authors, Queen's University professor David Gordon, says that when the suburban "tidal wave" washes over little communities such as Shelburne, their growth often spikes.

Its expansion limited by Lake Ontario to the south, Toronto has spread relentlessly in every other direction: to the east along the lake to Pickering, Ajax, Whitby and Oshawa; to the north into Vaughan, Richmond Hill, Newmarket and Markham, where tens of thousands of Asian immigrants have come to settle; and to the west toward Burlington and Hamilton, where many Toronto residents are moving to find housing they can conceivably afford.

Growth has been most intense to the northwest. It happened first in Mississauga, fuelled in part by Toronto Pearson International Airport and the economic hub that grew up around it. The area was mostly apple orchards and farmers' fields when Hazel McCallion moved there in the 1950s. When she left office in 2014 at the age of 93, after more than three decades as mayor, it was a suburban city of more than 700,000, with vast subdivisions and a downtown boasting skyscrapers that rear up in the distance as you approach from the north. It now ranks as Canada's sixth-biggest municipality, behind Edmonton.

Just above Mississauga is the ninth-biggest, Brampton. It had a population of 5,500 when future Ontario premier William Davis was born there in 1929, with the vast majority claiming British ancestry. Today, it is a teeming, multicultural place with almost 600,000 residents, many with roots in South Asia.

Drive half an hour north from Brampton and you reach Orangeville, with a population of about 30,000. It, too, is bursting at the seams, with big new subdivisions and shopping centres. Another 20 minutes up the road takes you to Shelburne.

The community was founded by William Jelly, the son of an Irish immigrant. His statue stands across from the pink-brick 1883 town hall. He saw growth coming, too, opening Jelly's Tavern and ordering a village survey before a railway from Toronto came through. The village grew from 70 souls in 1869 to 750 in 1877.

Today, it stands at the intersection of Highways 10 and 89, in a part of Dufferin County that features potato farms in the flatlands and country homes for well-off city folk in the scenic hills. Its location puts it on the far side of the Greenbelt, the crescent-shaped reserve that protects land on Toronto's periphery. But with development surging north, it no longer seems so distant from the metropolis. "Toronto is getting closer," said Ed Crewson, mayor from 1997 to 2014.

When he was growing up, Shelburne was, above all, an agricultural community. His father delivered feed to farmers from the local co-op. Farm-equipment dealers sold tractors in the town centre.

Although Shelburne is quickly becoming a bedroom community, it’s still a farming town: Dave Stitt, a miller with Sharpe Farm Supplies, keeps an eye on feed moving on a hopper.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

But that old economy was dying even then. From the time Mr. Crewson joined the town council at the age of 28, he felt the town needed to grow in order to prosper. As mayor, he helped put the foundations in place: a new water tower, new wells, a better sewer network.

When Toronto-driven growth started reaching the town a decade ago, Shelburne was ready. New cookie-cutter subdivisions that look much like the ones down the road in Orangeville and Brampton have sprung up – five of them since 2003, with another two expected to break ground this year. Between them, those two will have more than 500 new houses.

The town's population has soared from 3,800 in 2003 to 8,100 today. Chief administrative officer John Telfer says it could climb to 12,000, perhaps 14,000, in coming years. The town even got a Tim Hortons outlet a couple of years ago, a big event for a place that felt overlooked by the big chains.

"The growth spurt has been so quick," said Debbie Freeman, the British-born office manager of the Shelburne Free Press. "It's just full-steam ahead."

Homes on Cook Crescent in Shelburne.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

The dramatic run-up in Toronto real estate prices makes Shelburne seem cheap by comparison. You can still get a townhouse in the $360,000 range, up from $250,000 a couple of years ago. Local realtors say everything is selling – townhouses, bungalows, old Victorians, country estates.

Older people from parts south looking for a quiet place to retire are coming to town. So are young couples who want a decent-sized house for their growing families.

Youth worker Andrew James, 38, who has three young daughters, moved into a four-bedroom, 2,600-square-foot house, trading up from a two-bedroom townhouse in Mississauga. His friend Noni Thomas, 36, a music teacher, followed and now lives nine houses away.

Winsome Barrows, 51, moved to Shelburne from Brampton with her husband and daughter in 2015. She got her four-bedroom house for the low $300,000s, half the price of a similar place in Brampton.

Noni Thomas and her husband bought a detached home in a new subdivision in Shelburne several years after living in Brampton, Ont. Noni teaches music to the local children.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

But there is a cost. To get to her downtown Toronto office, she drives to Orangeville, catches a GO Transit bus to Brampton, takes the GO train to Union Station, then walks the final 10 minutes to work – 2 1/2 hours each way. She insists it is worth it. "We just fell in love with the town."

Feelings about today's boom are mixed. On the one hand, the growing town can afford such amenities as a first-class soccer complex with two fields. Local supermarkets are better stocked to serve a population whose tastes range beyond butter tarts. Plantain chips and jerk sauce are now on offer, though for traditionalists the Main Street pizza joint sells wings, fries, onion rings and "new deep-fried cheesecake."

There is more to do these days. The town is souping up its well-known August fiddle festival, rebranding it as the Shelburne Heritage Music Festival. In February, it held the third-annual Shelbrrr Fest, a winter festival with a snow-castle contest, dog sledding and a tube slide. On top of curling and hockey – the minor-league hockey team is the Shelburne Muskies – the town offers skateboarding at a sleek skatepark with metal ramps.

Jobs have come, too. KTH Shelburne Manufacturing, open since 1998, employs about 550 workers making auto parts for the Honda plant in nearby Alliston. Water-bottling firm Ice River Springs employs more than 50 in its corporate headquarters and bottle-recycling plant. About a third of employed residents work locally, and the rest go into Orangeville and parts of greater Toronto, town officials estimate.

Cathy Slear, co-owner of the Creative Hair Boutique in Shelburne, trims Jeff Coyle’s hair. Slear believes a bowling alley would be a good addition to the town since there’s not much for people to do locally. Coyle lives in nearby Honeywood but has also noticed the recent growth in the population of Shelburne.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

On the other hand, some see the small-town feel of the place slipping away. Heather Holmes, 56, helps run a decades-old family business on Main Street with an unusual mix of merchandise: appliances and musical instruments. "We don't know everybody now," she said. "It's bigger, faster."

Like it or not, though, change is coming to Shelburne and other places in the Toronto blast zone. Some towns, such as Streetsville in Mississauga, have been enveloped by the suburbs around them. Others, such as Stouffville, to the northeast of Toronto, are becoming bedroom communities, a process that is speeding up as authorities improve regional rail service. Commuters can travel into Union Station from Stouffville on the GO train. The community's population doubled from 2006 to 2011.

Shelburne decided some time ago that it was best to embrace change, not resist it. To cope with the coming growth, it would like to spruce up the faded downtown strip, get transit officials to run a GO bus up to Shelburne and attract more big stores so residents don't have to drive elsewhere to shop. "I'm a lifer," said Mr. Crewson, the former mayor, "but I believe growth and change are important."

Five new subdivisions have popped up in Shelburne since 2003.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

When columnist Marcus Gee visited Shelburne, he heard from locals about the town's historic lack of diversity. Many could remember only one non-white family, who ran a Chinese restaurant nearly 50 years ago. Back in the newsroom, Mr. Gee discovered a personal connection to that family: Globe and Mail photographer Fred Lum.

Mr. Lum's family left Shelburne when he was 7, heading back to Toronto, where he was born.

"It was the summer of '69 and my parents, two sisters, a brother, my grandparents and an uncle left small-town life in Southern Ontario for Toronto, where my parents, who didn't have the greatest command of the English language, would find a community they could fit into.

"We owned a Chinese restaurant/diner/greasy spoon, called The Tasty Cafe, that was a local hangout for high-school students.

"Small-town life was idyllic for a young kid back then. When the restaurant opened in the morning, it wasn't unusual for the back door to be swung open and I would take off for the fields with friends, or alone, and get lost in whatever our imaginations allowed. I knew I looked different from all the other kids (black hair versus blond!), but to everyone in town, I was just Fred, the Lum kid from the restaurant on Main Street.

"There were roughly 2,000 people back then and the population didn't budge much over the years until recently. The Shelburne I photographed this week looked radically different than the small hometown of my memories."