To get some insight into Toronto's housing problem, take a ride up the CN Tower and look out on the city. The first thing you notice is all the tall buildings – dozens of them in the downtown core just below you, more rising at key intersections along the Yonge Street corridor and still more in scattered bunches in the distance. The second thing you notice is the vast leafy neighbourhoods, many of them quite near the city centre. These low-rise districts still take up most of the city's land mass.

What is missing is anything much in between – the housing form that is being called the missing middle. As the city debates how to provide decent, affordable living quarters for its growing population, expect to hear that phrase more and more.

Toronto has lots of condominium towers and lots of sprawling suburban subdivisions. It is good at building up to the sky and good at building close to the ground. It is not so good at building small apartment blocks, stacked townhouses, multiplexes, courtyard apartments and other building types that fall between the sky-high tower and the single-family home. The city is the poorer for it. A recent study by the Canadian Centre for Economic Analysis found that 45 per cent of residents of the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area live in detached homes and 35 per cent in apartment buildings, leaving just 20 per cent in the missing middle. That is a problem for the many Torontonians who can't afford (or don't want) a detached house and yet aren't willing to live in a niche 30, 40 or 50 storeys up in the air.

It doesn't need to be that way. In the older parts of central Montreal, row houses, walkups and apartment blocks are common. The result is plenty of urban density and street life. In Mexico City, you find lively central neighbourhoods with buildings of four, five and six storeys. You get lots of density without a lot of towers. Many European cities are like this, too. Think of Paris, with its grand boulevards lined by classic apartment buildings.

It isn't just old cities that manage this kind of building form, either. Cities such as Copenhagen are building plenty of creative new medium-density housing. Toronto has far too little like it.

Toronto's missing middle is a product of how the city grew. Like many North American cities, it spread relentlessly outward into the surrounding countryside, especially after owning a car became more common. Until recently, there was not much need for denser housing types.

Public policy plays a role, too. Zoning rules make much of Toronto off limits to just about anything except detached houses. This is the yellow belt, so named because it bears that colour on the colour-coded city zoning map.

Planning consultant Sean Galbraith says that 38 per cent of the city's land mass and 60 per cent of its residential areas are yellow. To illustrate, he undoes the specially made bowtie that he wears showing the zoning map. Much of the tie is – yes – pale yellow.

The zoning rules were meant to protect one of Toronto's glories: its pleasant, stable residential neighbourhoods. At one time, city planners worried they would be wrecked by an invasion of apartment towers.

But the result, Mr. Galbraith says, is to "shrink wrap" yellow-belt neighbourhoods, preventing them from evolving with the times and keeping out residential projects such as multiplexes that might add a modest degree of density. "It is a giant wasted opportunity," he says. "They are overprotected."

The number of people living in many of those neighbourhoods is shrinking. Families are smaller than they were. Houses that might have held five, six, seven – or more – people 50 years ago now hold two, three or four; sometimes, only one.

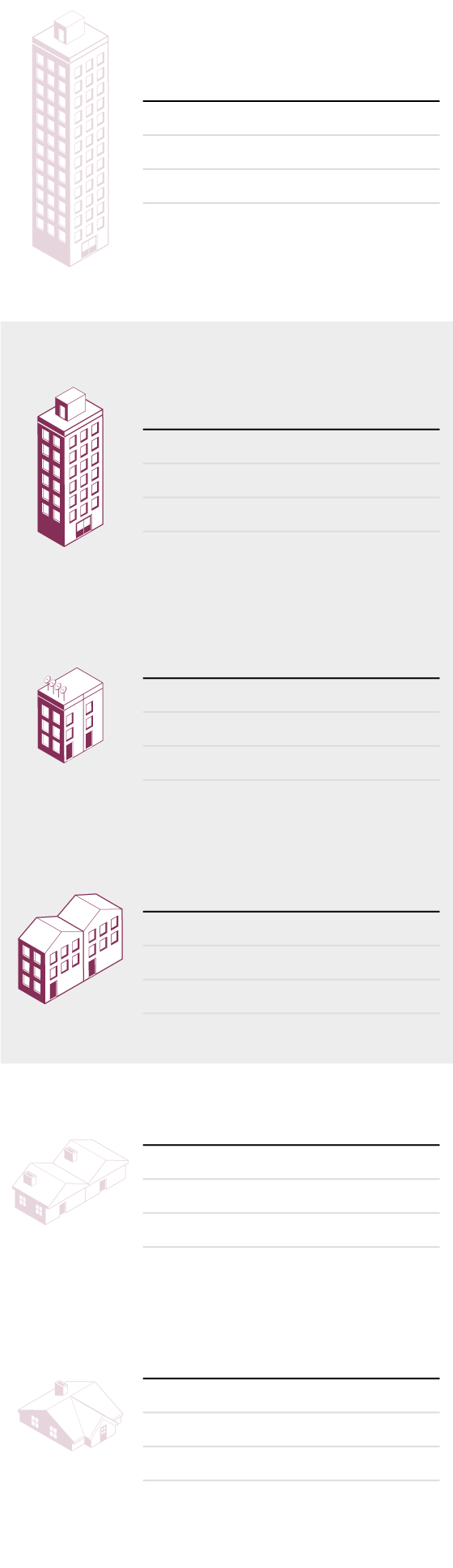

HIGH RISE

Storeys

12+

Avg. new price

$562,403

Avg. people per unit

2.03

ThE MISSING MIDDLE

MID-RISE

Storeys

Five to 11

Avg. new price

$562,403

Avg. people per unit

2.32

STACKED TOWNHOUSE

Storeys

Three to four

Avg. new price

$520,400

Avg. people per unit

2.32

TOWNHOUSE

Storeys

One to three

Avg. new price

$896,589

Avg. people per unit

2.88

SEMI-DETACHED

Storeys

One to three

Avg. new price

$845,951

Avg. people per unit

3.12

DETACHED

Storeys

One to three

Avg. new price

$1,783,417

Avg. people per unit

3.19

THE GLOBE AND MAIL,

SOURCE: RYERSON CITY BUILDING INSTITUTE

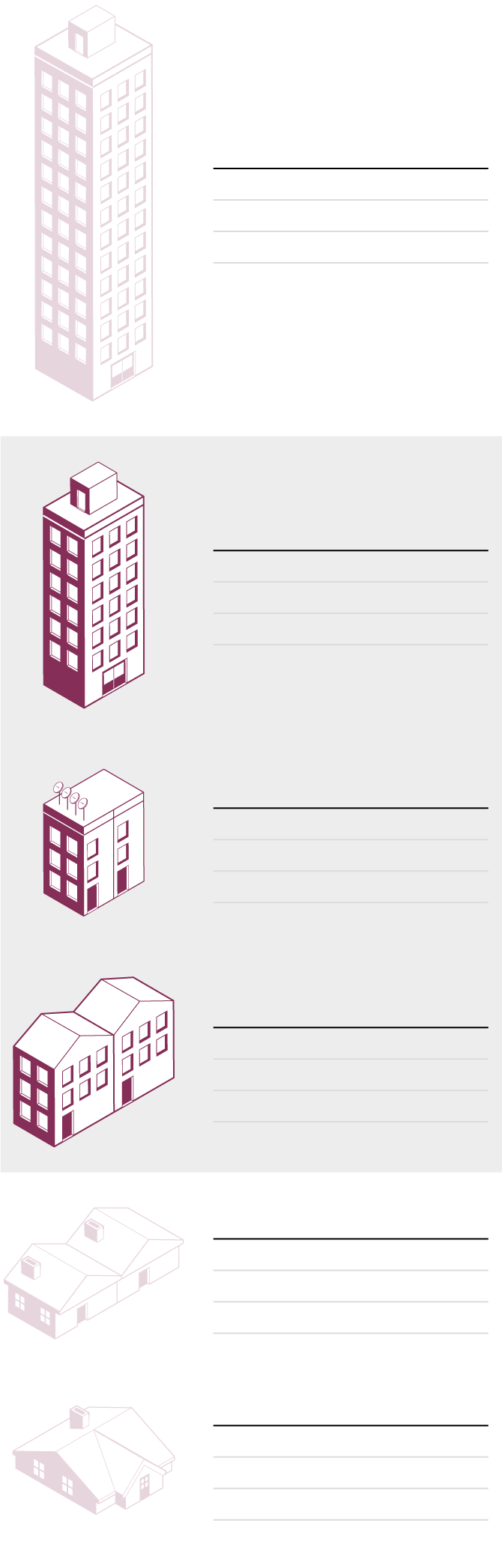

HIGH RISE

Storeys

12+

Avg. new price

$562,403

Avg. people per unit

2.03

ThE MISSING MIDDLE

MID-RISE

Storeys

Five to 11

Avg. new price

$562,403

Avg. people per unit

2.32

STACKED TOWNHOUSE

Storeys

Three to four

Avg. new price

$520,400

Avg. people per unit

2.32

TOWNHOUSE

Storeys

One to three

Avg. new price

$896,589

Avg. people per unit

2.88

SEMI-DETACHED

Storeys

One to three

Avg. new price

$845,951

Avg. people per unit

3.12

DETACHED

Storeys

One to three

Avg. new price

$1,783,417

Avg. people per unit

3.19

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: RYERSON CITY BUILDING INSTITUTE

HIGH RISE

Storeys

12+

Avg. new price

$562,403

Avg. people per unit

2.03

ThE MISSING MIDDLE

MID-RISE

Storeys

Five to 11

Avg. new price

$562,403

Avg. people per unit

2.32

STACKED TOWNHOUSE

Storeys

Three to four

Avg. new price

$520,400

Avg. people per unit

2.32

TOWNHOUSE

Storeys

One to three

Avg. new price

$896,589

Avg. people per unit

2.88

SEMI-DETACHED

Storeys

One to three

Avg. new price

$845,951

Avg. people per unit

3.12

DETACHED

Storeys

One to three

Avg. new price

$1,783,417

Avg. people per unit

3.19

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: RYERSON CITY BUILDING INSTITUTE

Two-thirds of the city's 140 neighbourhoods have seen their population density decline or stagnate since 1986, according to an independent study by urban planner and researcher Cheryll Case. In such neighbourhoods, schools are more likely to close or suffer from chronic under-enrolment. Transit authorities run fewer buses because there aren't enough riders.

Adding more people and more dense building types – "modest intensification," as Mr. Galbraith puts it – just makes sense, especially in a growing city with a shortage of housing that people can afford. Torontonians like to complain that the city has too many tall condos and too many overpriced houses. Building the missing middle is one obvious way out.

But city hall doesn't make it easy. George Popper, an architect and developer with decades of experience, complains that it is getting harder and harder to build the kind of missing-middle projects that are his specialty. He recently drew up plans for a small development near Victoria Park Avenue and Highway 401 that would have taken the place of a small church that is closing its doors. The plans show single-family homes on one side, facing a residential neighbourhood, and townhouses on the other, facing a commercial plaza. Mr. Popper says planners told him the project was inappropriate for the neighbourhood.

He complains that the 11-unit townhouse project that he designed on Brunswick Avenue in the Annex neighbourhood a couple of decades back would be impossible to build today. Planners would insist a garbage truck must be able to turn around on the small property, a provision that makes it tough for architects to design usable space.

A recent update to city planning rules will make it still harder to construct the missing middle, Mr. Popper says. The new policy emphasizes that development should respect the "prevailing" scale and character of the surrounding building and of the neighbourhood. The result, he fears, will be to hold back creative new missing-middle projects.

He and other developers say it is a chore to build even mid-rise buildings, a type that city planners say they wish to encourage. The city's "Avenues" program was supposed to make it easier for builders to put buildings of several storeys along main streets such as Queen or College. The results have been disappointing. Though some mid-rise condos are going up, most of these streets are still lined with the same two- or three-storey shophouses that have been there for decades. Another density opportunity squandered.

Cherise Burda, executive director of the Ryerson City Building Institute, says that "outdated zoning, slow approvals processes, community opposition and infrastructure-upgrade costs often make intensification and missing-middle housing cost-prohibitive." As a result, she wrote in July, "it's more affordable for municipalities and developers to build high or build out in the suburbs where land and infrastructure are cheaper."

It is not that Toronto doesn't know how to build missing-middle housing. Toronto's Q4 Architects has been building attractive mid-density projects for years in suburbs such as Milton, Oakville and Mississauga. The firm's principal, Frances Martin-DiGiuseppe, says there is lots of opportunity for more, not just in stable neighbourhoods but on old industrial sites, surplus schools and shopping malls near to transit. "As soon as you go beyond the core you can see lots of opportunities for development," she says. Why not make use of the wasted space in all those strip malls on suburban avenues, building new housing and stores on them, she asks. Why not allow people to build coach houses above their garages.

Toronto is already looking at whether to permit laneway housing, opening up the city's 250 kilometres of lanes to small houses and suites behind existing houses. They could accommodate adult children, aging parents and others. Recent changes to Ontario's Building Code should help, too. Since 2015, builders have been allowed to construct wood-frame housing of up to six storeys. Using wood can make missing-middle stuff a lot cheaper.

With the housing problem in the headlines, the city seems suddenly open to change. "We seem to be having a conversation about where people are going to live," Ms. Martin-DiGiuseppe says. "Where are my kids ever going to live? Will they ever be able to buy a house? Now that people are talking about the missing middle I think it will lead to changes."

Let's hope she is right. Tall buildings are fine. Lovely, stable neighbourhoods are great. But if Toronto wants to lick its housing problem, it is going to have to fill the missing middle.