It landed like an alien spacecraft: the curviest and most innovative thing in a city of straight lines and Victorian brickwork. When City Hall opened in 1965, it instantly transformed Toronto's image of itself.

Fifty years later, that building and Nathan Phillips Square are Toronto's civic and symbolic heart. This summer, I saw the square packed with thousands of people for concerts during the Panamania festival; the newly renovated square felt like the city's grand yet comfortable living room. Like all great design, it seems inevitable.

But as we mark the complex's 50th anniversary – there is a public party there on Sunday – it's worth remembering the truth: The hall and square, with their exuberant architecture by the Finn Viljo Revell, just barely came to pass. Toronto surprised itself, with the sort of bold leadership that doesn't exist in the city today.

This month an exhibition, a series of talks, an online exhibit and a new book start to unpack some of this complex history – which has lessons for Toronto today.

Toronto in the mid-1950s was much smaller, still deeply Protestant and colonial. The project began with political infighting and a mediocre design. And during the eight years from design to opening day, it evolved through Toronto's contrary strands of boosterism, parochialism, parsimoniousness (there were extended political battles over the furniture and the Henry Moore sculpture on the square) and prudery. (The idea that alcohol might some day be served at a City Hall restaurant prompted angry protests.)

Somehow, it worked out.

The intricate design of Toronto’s old city hall building, right, contrasts with the streamlined shape of the new.

JOHN REEVES/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The exhibition Shaping Canadian Modernity, which runs until Oct. 9 at Ryerson's Paul H. Cocker Gallery, looks back to the design competition of 1957 that gave Mr. Revell the job. Mayor Nathan Phillips had successfully pushed for a global competition that would produce "a symbol of Toronto, a source of pride and pleasure to its citizens." And with more than 500 entries from 42 countries, it captured a cross-section of the world of architecture. "The competition has global significance," says Ryerson architecture professor George Kapelos, one of the exhibition's curators. "City Hall becomes a petri dish for new ideas about the making of the city."

Less than a year before, a competition had selected an iconic design for Sydney's Opera House. Toronto, choosing to follow that example, opening its doors to the world with a jury of modernists including Eero Saarinen, was itself a sign of ambition.

Architectural models in the City Hall design competition, 1957.

CITY OF TORONTO ARCHIVES

And at this moment it wasn't clear what a modernist civic building and square should look like. The formulas that would shape Toronto and other cities – the tower in the park, the curtain-wall office tower, the multi-levelled modernist plaza – weren't yet inevitable.

The Revell design wasn't particularly obvious at first; there is a story that Mr. Saarinen showed up a day late for the jury meeting and asked, "Show me your discards" – and pulled Mr. Revell's model out of the reject pile.

The Ryerson show hints at the range of possibilities that the jury, led by the deeply influential Torontonian architect and educator Eric Arthur, passed over. You can also sample them online, thanks to the Toronto Public Library.

SEVEN REJECTED DESIGNS FOR CITY HALL

(

Photos courtesy of the Panda Collection, Canadian Architectural Archives, University of Calgary)

There is an elegant tower-and-pyramid by the Japanese architect Kenzo Tange; a lozenge-shaped slab by the Indian B.V. Doshi; a low, hollow square by future Pritzker Prize winner I.M. Pei; and a sculptural, environmentally sophisticated design by a group of Harvard students led by John Andrews, who would design the CN Tower. (All 500 of them deserve to be published, and this has never happened.

Civic Symbol, a new history by Christopher Armstrong, and Competing Modernisms, by Mr. Kapelos, each capture a slice of this rich trove.)

Mr. Revell partnered up with the Toronto firm of John B. Parkin Associates, one of the leading modernist firms in Canada, and his office collaborated with Parkin until Mr. Revell died in November, 1964, less than a year before the building was completed.

Finnish architect Viljo Revell surveys his work in October, 1964, shortly before his death.

HARRY McLORINAN/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

While he did not live to see its completion, his design emerged relatively intact. It is both elegant and democratic. From the square through the lobby and public spaces, visitors enjoy sculptural but hospitable spaces made of fine materials: crafted concrete and carefully worked marble. The council chamber has room for 300 spectators to sit, with powerful symbolism, overlooking their representatives at work.

Viljo Revell’s design for the City Hall council chamber.

PANDA COLLECTION, CANADIAN ARCHITECTURAL ARCHIVES, UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY

While most of the office space in the towers is merely generic, the layout does force councillors and city staff to mix with citizens. Mayor Rob Ford, when the scandal of his crack use broke, couldn't escape the media through some back stairwell. There is none. That is no accident.

The success of the square, though, is a happy historical accident. "This was a moment when urban design" – the discipline that's concerned with the arrangement of blocks, streets and other elements within the city – "had hardly been born," says the architect and educator George Baird, who speaks Sept. 24 about the square's urban design. "Because that period of modern architecture was so uninterested in the contextual position of a building in a city, it was not good at creating formed public space." And yet, "it works very well psychologically." To Mr. Baird's eyes, this is because of the elevated walkway that frames the square, making it feel like a room while still being easy to enter and exit. The walkway, however, was supposed to connect across the street in an elevated network like Calgary's Plus 15: an idea that was soon abandoned, "and what a close call for Toronto!" Mr. Baird adds.

That's just one of many tangents – architectural, social and economic – in the City Hall story, which is one of the decisive narratives in Toronto's history. The recent essay collection The Ward explores the history of the working-class neighbourhood and melting pot which was bulldozed, in part, for City Hall.

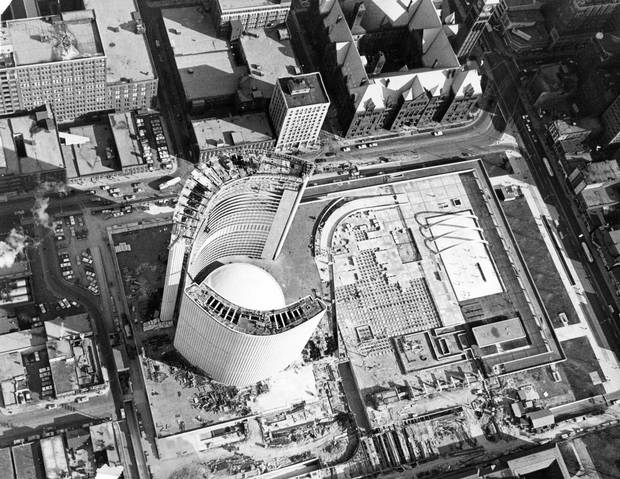

City Hall under construction, Dec. 1, 1964.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL

But reading through Mr. Armstrong's Civic Symbol, what's clearest is the scale of Mr. Phillips's accomplishment. With few strong allies, he haggled and coaxed his own council and the new Metro government until he lost a bid for re-election in 1962. There was bitter controversy about the open competition; the winning design; the details of construction; even the furnishing of the building, which was done in high modernist style by Knoll and cost a bit more than the alternative from Simpson's.

The curvy, unusual building had to be redesigned for economic reasons, and still wound up substantially more expensive – at around $25-million – than the city had originally intended. In the end it went modestly over budget, was finished years late, and the process was punctuated by bickering between the city, the architects and the contractors, who went into bankruptcy in 1967. (Mr. Revell was hammered financially, too.)

And who remembers any of that? City Hall and Nathan Phillips Square make an enormous contribution to the city, precisely because they're the product of fresh ideas and high ideals.

Toronto’s new City Hall building is featured in The Globe Magazine on Jan. 16, 1960.

ERIK CHRISTENSEN/FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

There is no way in today's political climate that the city would take on such an initiative. Major public buildings today don't go to obscure foreign architects with strong ideas. They go to teams of licensed and experienced consultants; they are cheapened and rationalized. Even the new St. Lawrence North Market building, which is the product of a design competition, is being pared down and crammed with functions that don't belong.

The recent repairs and renovation of Nathan Phillips Square, a complex project that is welcome but unfinished, has been a political football. Memo to Mayor Tory: Nobody names a square after the guy who demanded cost savings. You don't build a culture on efficiencies. For that you sometimes need stone and concrete, and you need to make room for ideas with some curves.

City Hall 50th Anniversary Celebration, Sunday 12-5 p.m.; George Baird lecture, Sept. 24, 7 p.m., council chambers. All events at City Hall and Nathan Phillips Square, 100 Queen St. W.

Shaping Canadian Modernity: The 1958 Toronto City Hall and Square Competition and Its Legacy; opening Sept. 17, 325 Church St. Runs through Oct. 9.

TORONTO IN ART AND ARCHITECTURE: MORE READING

Picturing the city: Toronto City Hall’s little-known art collection

1:47