California has seen droughts before, but this one just isn't letting up. As Ivan Semeniuk reports, the state's governor has ordered the first mandatory water restrictions, but will it be enough?

From bad to worse

but will it be enough?

THE CAUSES

Warm temperatures and a lack of precipitation put California on course for the epic drought that has beset the state for the past four years. For example, from October, 2013, to September, 2014, California received less than 60 per cent of the average rainfall for a 12-month interval. That has kept water supplies low, particularly in the San Joaquin Valley, in the south-central part of the state.

Warm temperatures and a lack of precipitation put California on course for the epic drought that has beset the state for the past four years. For example, from October, 2013, to September, 2014, California received less than 60 per cent of the average rainfall for a 12-month interval. That has kept water supplies low, particularly in the San Joaquin Valley, in the south-central part of the state.

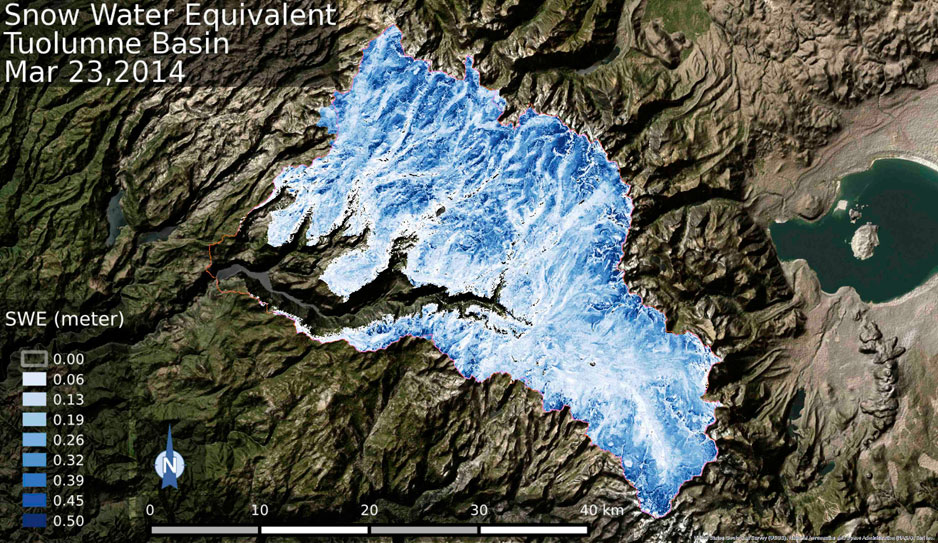

One of the warmest winters on record has exacerbated the problem. Much of the precipitation in the mountains over the past few months has fallen as rain rather than snow and has evaporated or run off too quickly. The lack of snow now means there will be little water left to recharge depleted reservoirs this year.

“Stream flow has been dropping like a stone,” says Eric Luebehusen, who monitors drought for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The situation is showing no sign of letting up. Temperatures have been averaging about 5 C above normal, and precipitation over the past month is just 10 per cent of what is normal at this time of year. With summer approaching, conditions are shaping up to produce an ominous shortage of water for many communities across the state.

GROUNDWATER

Much of California, especially the agricultural heartland of the Central Valley and the southern, urban regions of the state, draws its water from enormous projects that ferry surface water from the mountains to where it is needed. This water is monitored, and permits are required for its use.

Much of California, especially the agricultural heartland of the Central Valley and the southern, urban regions of the state, draws its water from enormous projects that ferry surface water from the mountains to where it is needed. This water is monitored, and permits are required for its use.

Groundwater is a different story, says Ruth Langridge, who specializes in law and water policy at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Its use has largely gone unchecked, and with the drought in full swing the concern is that groundwater supplies will be overdrawn to the point where they cannot recover.

“You want that groundwater there because it’s your backup when you don’t have those surface water supplies,” she says.

Land subsidence and saltwater intrusion are signs that too much groundwater has already been pumped out in some communities.

Last year, California passed its first measures aimed at reining in groundwater use, but they are to be phased in gradually, while the number of wells being drilled has skyrocketed.

SEVERITY

This week, virtually the entirety of California is abnormally dry, with more than 93 per cent of the state’s land area under severe drought – as dry as would normally be expected once a decade. What is most alarming is that 41 per cent of the land area is in exceptional drought. Such conditions might arise only once every 50 to 100 years. In general, California has experienced this level of drought only a handful of times in its recorded history.

This week, virtually the entirety of California is abnormally dry, with more than 93 per cent of the state’s land area under severe drought – as dry as would normally be expected once a decade. What is most alarming is that 41 per cent of the land area is in exceptional drought. Such conditions might arise only once every 50 to 100 years. In general, California has experienced this level of drought only a handful of times in its recorded history.

A recent study published in Geophysical Research Letters looked at signs of past droughts based on growth rings in trees. The results suggest the current drought is California’s worst in 1,200 years. Such a time span is a headline grabber, but a more relevant issue for Californians is whether periods of exceptional drought are becoming more common as the climate warms.

Californians try and cope with the drought and new water restrictions.

WATER RATIONING

For the first time in the state’s history, California has imposed mandatory water restrictions in urban areas. In an executive order, Governor Jerry Brown said more than 400 local water agencies will now be required to reduce water consumption by 25 per cent relative to 2013 levels.

For the first time in the state’s history, California has imposed mandatory water restrictions in urban areas. In an executive order, Governor Jerry Brown said more than 400 local water agencies will now be required to reduce water consumption by 25 per cent relative to 2013 levels.

Residential use accounts for much of the water affected by the order, which will likely lead to curtailing the use of water to keep lawns, golf courses and cemeteries green.

“People should realize we are in a new era,” Mr. Brown said at a news conference on Wednesday. “The idea of your nice little green lawn getting watered every day – those days are past.”

The order does not apply to the large farms that draw the lion’s share of the state’s water supply; however, landowners will be required to step up their reporting of water consumption.

CROPS

California’s Central Valley is the largest U.S. supplier of a wide range of food crops, cereal crops, vegetables, fruits and nuts. And whether it’s tomatoes, grapes, strawberries or melons, it all depends critically on water.

California’s Central Valley is the largest U.S. supplier of a wide range of food crops, cereal crops, vegetables, fruits and nuts. And whether it’s tomatoes, grapes, strawberries or melons, it all depends critically on water.

For growers, the most serious risk of a prolonged drought is to tree-based crops such as almonds or figs. Once trees are lost, it takes years to recover, so irrigation efforts typically prioritize trees. As water becomes scarce, less profitable crops such as alfalfa or those that are water-intense, such as rice or cotton, are likely to see the greatest declines, with an effect on prices.

LIVESTOCK

The drought is having an impact on livestock, particularly sheep and cattle, which are facing the drying out of vast stretches of their grazing land. As a stopgap, ranchers can import feed at a relatively high cost. But over time, the drought is forcing some to cull herds and auction off animals at reduced prices. California’s dairy industry, which accounts for 21 per cent of the U.S. milk supply, has also been hit by rising feed costs that sent milk prices spiralling upward last year.

The drought is having an impact on livestock, particularly sheep and cattle, which are facing the drying out of vast stretches of their grazing land. As a stopgap, ranchers can import feed at a relatively high cost. But over time, the drought is forcing some to cull herds and auction off animals at reduced prices. California’s dairy industry, which accounts for 21 per cent of the U.S. milk supply, has also been hit by rising feed costs that sent milk prices spiralling upward last year.

The difference a year makes

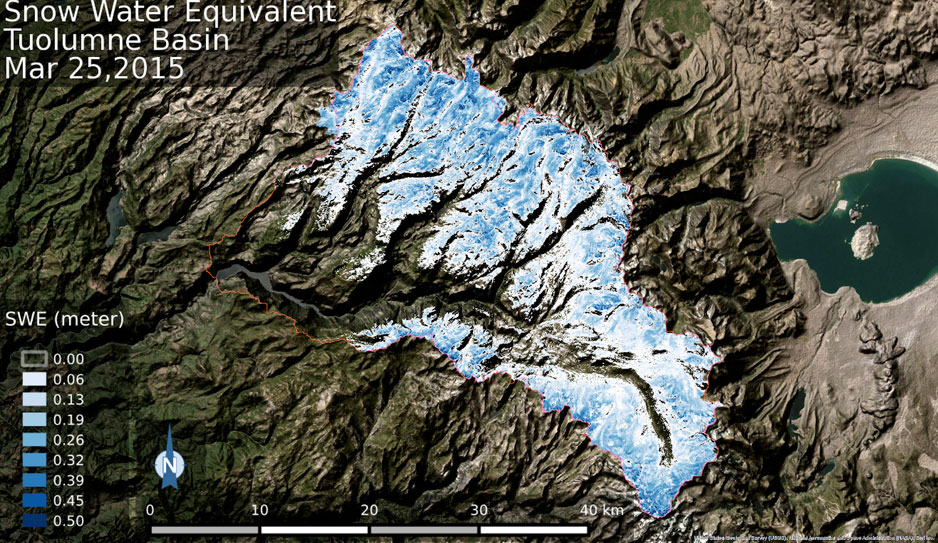

Snow water equivalent Toulumne Basin, California.

WILDFIRE RISK

California has a Mediterranean climate, which means warm, dry summers. That implies that in much of the state there’s always the risk of fire at some point in the year. But now, because of the ongoing drought, forests are generally much drier than they should be at this time of year.

California has a Mediterranean climate, which means warm, dry summers. That implies that in much of the state there’s always the risk of fire at some point in the year. But now, because of the ongoing drought, forests are generally much drier than they should be at this time of year.

“We’re starting off the fire season way ahead of schedule,” says Max Moritz, a fire scientist with the University of California, Berkeley.

Stands of dead vegetation from earlier years of this drought now offer plenty of potential fuel for raging fires. And, in most cases, this extra fuel is far too abundant to remove as a precaution.

While that doesn’t guarantee that 2015 will be a bad year for wildfires in California, it certainly stacks the deck. It also underscores a message that Dr. Moritz and his colleagues have been increasingly trying to convey to the public: Fire risk is a reality that is not going to be eliminated from the California landscape. Like earthquakes, it’s something the state’s residents and policy makers will have to learn to live with through better land-use practices.

THE CLIMATE CONNECTION

While severe droughts are part of California’s climate history, the current episode is in keeping with projections that suggest such events may be lasting longer and getting worse. For the past two years, North America has been in the grip of a weather pattern that has kept a high-pressure system stubbornly parked over the Pacific. This has helped to channel warm, dry air up the West Coast, perpetuating drought conditions in California. Meanwhile, cold air has been moving down from the Arctic and across the northeast, where temperatures have been unseasonably low.

While severe droughts are part of California’s climate history, the current episode is in keeping with projections that suggest such events may be lasting longer and getting worse. For the past two years, North America has been in the grip of a weather pattern that has kept a high-pressure system stubbornly parked over the Pacific. This has helped to channel warm, dry air up the West Coast, perpetuating drought conditions in California. Meanwhile, cold air has been moving down from the Arctic and across the northeast, where temperatures have been unseasonably low.

Some climate scientists have suggested that the persistence of such weather patterns is the result of a jet stream that has been weakened by global warming.

FUTURE RESILIENCE

The question that lurks in the background of the unfolding California drought is to what extent it represents the new normal. If average temperatures continue to increase due to climate change, droughts will necessarily become more

The question that lurks in the background of the unfolding California drought is to what extent it represents the new normal. If average temperatures continue to increase due to climate change, droughts will necessarily become more

Many experts say what the state is experiencing today should provide the impetus to make the shift to a better water system. High-tech monitoring of water supplies and advanced irrigation technologies can help, as can better management of groundwater. There is also room for expanding the state’s reservoir system in certain areas.

Creating potable water out of the ocean may be a viable option, but only to a limited degree because desalination consumes so much energy.

Less likely is the prospect that California will be going farther afield any time soon – to the Columbia River Basin of the Pacific Northwest or to Canada – to boost its water supply. While such schemes have been floated for decades, they remain expensive and contentious. The idea of a conduit shipping water southward from Canada would likely be opposed even more strongly than the Keystone XL oil pipeline.

In the short term, the drought is likely to move the state toward more rigorous water management as it tries to build resilience and brace for a warmer future.

“One thing about a crisis is that you can get things done you can’t get done otherwise,” says Doug Parker, director of the California Institute for Water Resources in Oakland. “So I’m hoping we’re going to see some new policies coming out of the state this year that are going to help us in the long term.”