When Margaret MacMillan resigned in ‘shock’ and ‘dismay’ from a foundation that promotes Canadian studies in the U.K, it brought to light a battle between the once academic-led board and Canada’s High Commission

Margaret MacMillan thinks her name may have been crossed off the invite list for dinners at Canada House. But Canada’s preeminent historian is so angry at the “high-handed” way the Canadian High Commission in London treated a fellow academic that she doesn’t care.

The High Commissioner, Gordon Campbell, is also peeved. He’s miffed at the complaints directed his way by Prof. MacMillan and others since the High Commission intervened to break a deadlock on the board of directors of an once-obscure organization called the Foundation for Canadian Studies in the United Kingdom.

With some of the heavyweights of the Canadian community in London publicly at odds, drawing up the invite list for this year’s Canada Day celebrations has become more complicated. Even Diana Carney, a think-tank adviser and the wife of Bank of England Governor Mark Carney, has been dragged into the dispute.

She joined Prof. MacMillan and two other academics last month in resigning from the board of the foundation, which was founded in 1975 to promote the academic study of Canada in the U.K. with a $2.5-million endowment.

Travel grants to help researchers delve into earnest subjects like the third book in a trilogy on English emigration to Canada, and a PhD student’s dissertation on “representations of HIV/AIDS in Québécois Cinema,” fell far short of what the flashy Mr. Campbell, a former premier of British Columbia, felt the foundation could be achieving. Following a power struggle that saw the board of directors flooded with High Commission employees – which led to a walkout of all but one of its academic members – the foundation most recently covered travel costs so that Alberta designer Sid Neigum could participate in London Fashion Week.

The foundation’s original mandate was “the advancement of the education of the public in the United Kingdom in matters relating to Canada,” primarily through the funding of Canadian Studies research chairs at several UK universities. Following the fracas, the foundation’s website was amended to say it is “now expanding this to consider research that is directed at issues that are of strategic importance to both Canada and the UK, such as energy, transport, communications, the sustainable use of natural resources, multiculturalism and the welfare of indigenous peoples.”

The squabble has seen Mr. Campbell accused of bullying and suggestions raised of interference by either the Prime Minister’s Office or the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade in Ottawa. Critics accuse the High Commission of wanting to use the foundation’s money – all of it raised via private donations – to carry out programs the High Commission can no longer afford to pay for after funding cuts by the federal government.

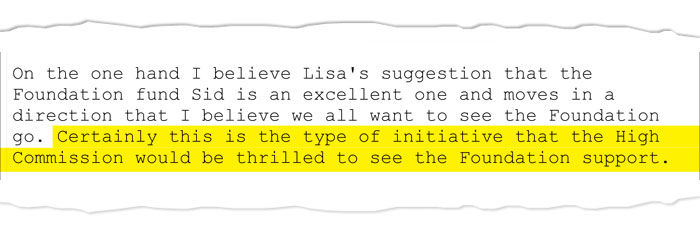

In a Jan. 29 e-mail to the board, Mark Richardson, the commercial counsellor at the High Commission, applauded the initiative to use the foundation’s money to help fund Mr. Neigum’s trip (although he had initially suggested postponing the decision for procedural reasons).

“Certainly this is the type of initiative that the High Commission would be thrilled to see the foundation support,” Mr. Richardson wrote. “The High Commission is involved in London Fashion week and we would very much like to see Sid involved and profiled. He has approached us for funding which we are struggling to find. It’s near our end of fiscal year and the funding which we could use to support him appears to be spent.”

The whole affair has drawn comparisons to how the Conservative government in 2012 dismantled the Montreal-based Rights and Democracy, another agency that was supposed to operate at arm’s length from the government, after flooding the group’s board of directors with loyalists.

The controversy in London began earlier this year when the High Commission launched an effective takeover of what Mr. Campbell called the foundation’s “dysfunctional” board of directors. That board had become deadlocked over whether the foundation should stick to its focus on academic exchanges or branch out into less arcane and more headline-grabbing efforts.

The infighting had become so bad that Robert C. Hain, the board’s chairman and the head of a London-based investment fund, resigned in October. In an e-mail to The Globe and Mail, he explained his decision diplomatically, saying it had become “a bit difficult to reconcile all the points of view.”

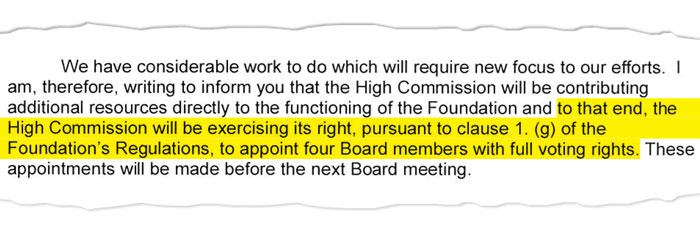

The split broadly pitted the board’s academic members against those drawn from the Canadian business community in the U.K. After Mr. Campbell’s intervention, the business side won out. In January, Mr. Campbell set the foundation on its new course by flooding the board with four new members, three of whom are High Commission staff. Shortly afterward, the senior academic on the board, Leeds University professor Rachel Killick, was forced out.

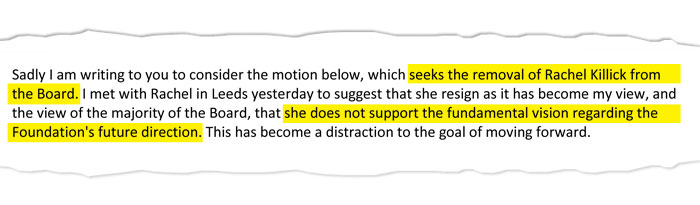

That’s when the Canadian cat fight began. In his e-mail informing the board that he was seeking to remove Prof. Killick “effective immediately,” Mr. Richardson, said Prof. Killick’s refusal to support the foundation’s proposed change in direction “has become a distraction to the goal of moving forward.”

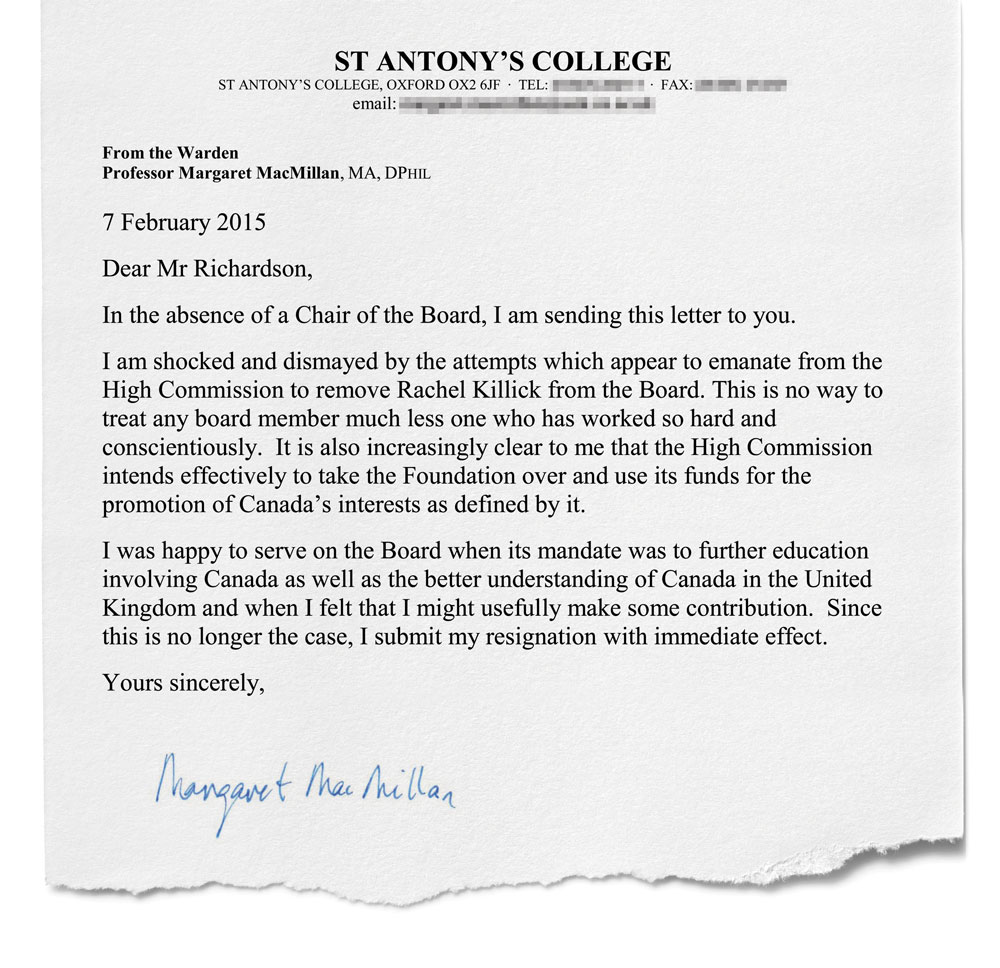

Within hours, the normally reserved Prof. MacMillan had sent a blistering retort. “I am shocked and dismayed,” Prof. MacMillan’s letter of resignation, dated Feb. 7, read. “It is also increasingly clear to me that the High Commission intends to effectively take the foundation over and use its funds for the promotion of Canada’s interests as defined by it.” Three other letters of resignation – from Ms. Carney, as well as University of Birmingham lecturer Steve Hewitt and University of Ulster lecturer Susan Hodgett – quickly followed.

But Prof. MacMillan, the warden of St. Anthony’s College at Oxford University, doesn’t blame Mr. Richardson. She and the other academics are convinced that he was doing the bidding of Mr. Campbell – and they suspect the High Commissioner was getting his orders from Ottawa.

“The government in Ottawa has a reputation for trying to control things and for being highly centralized … and I think the present High Commissioner has been very effective and has very good connections in Ottawa,” Prof. MacMillan said in an interview.

Ms. Carney, who advises the Canada 2020 think tank, declined to comment on the affair. Rather than siding fully with the academics, they said she called on the entire board to step down so that the foundation could have a fresh start.

Others who quit the board said they did so because they no longer wanted to be associated with it after seeing how Prof. Killick was deposed. “I personally couldn’t keep working with people that had bullied a colleague,” said Dr. Hewitt, who teaches American and Canadian Studies.

Mr. Campbell says he was surprised by Prof. MacMillan’s words in particular, and denied Ottawa had directed the handling of the foundation. “We were asked to intervene by the board. The board came to us and said this situation was dysfunctional and we must move forward … This is not something we did, this is something we were asked to try and resolve,” Mr. Campbell said in a telephone interview. “At no time did anyone from Ottawa suggest that we should be doing anything at all.”

Mr. Campbell said he became concerned with the foundation’s direction last year when it lost its status as a Canadian charity after almost 40 years (although the board remains a registered charity in the U.K., where it does nearly all its fundraising). However, the academics who quit the board say the decision to revoke the foundation’s charitable status was a politicized one, orchestrated by the High Commission to ramp up pressure on the board. The academics felt there was an informal deadline to adopt a new direction for the foundation before the summer, when Mr. Campbell is due to retire as high commissioner, amid rumours that he may run for the Conservatives in this fall’s federal election.

A Dec. 2 letter from Mr. Campbell to the board of directors appears to support the academics’ case. It also casts doubt on Mr. Campbell’s assertion that the federal government was not involved in the fracas.

“I need to advise you of the decision taken in Ottawa not to renew the foundation’s charitable status at this time. I understand from my colleagues in Ottawa that our renewal request would be entertained if the foundation were to expand its mission,” the letter reads.

Mr. Campbell called the charge of bullying “absolute nonsense.” He said the dispute had come about because “some people don’t like any kind of change.” He flatly denied any interest in returning to politics.

The new chairwoman of the foundation’s board, Fiona Colegrave, a Winnipeg-born independent business consultant, said she was “disappointed” with the attacks on Mr. Campbell. “I am personally thrilled to have the High Commissioner’s support because that helps us do what we do,” she said. “But he is not running the show. At all.”

The academic at the centre of the dispute, Prof. Killick, says the atmosphere on the board got nastier as soon as Mr. Campbell told a meeting last June that the foundation needed to broaden its focus beyond funding academic studies, and particularly when she tried to protest the High Commissioner’s plans.

But Prof. Killick says Mr. Richardson travelled to Leeds last month to tell her she could either resign her position as vice-chairwoman voluntarily or have the newly stacked board force her out. “He said I was too legalistic. I think he meant that I kept objecting to things that were not in line with the mission of the foundation,” she said. Prof. Killick refused to step down, so she was voted out under a motion proposed by Mr. Richardson and seconded by two other High Commission representatives on the board.

“I think the biggest problem is this particular High Commissioner thinks that having a big event in London is going to have more impact [than funding ongoing academic studies]… they don’t see that as a useful function, because it’s not going to produce some major news story. But what it does produce is people here [in the U.K.] who know something about Canada.”

From the academics’ point of view, the battle, for the moment, is lost. Dr. Hewitt acknowledged that the mass resignation by the academics has left the High Commission and the business members of the board in control of the future direction of the foundation and the grants it gives out.

What lingers is the sting left by the words used in this very un-Canadian mudslinging match. “I’d hope that Margaret considers herself a friend of mine, but that’s for her to decide,” Mr. Campbell said.

Prof. MacMillan took a similar tone. “I’ve heard nothing from the High Commissioner [since the resignation letter]…. Maybe I’m not on his dinner list any more.”