On the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, Setsuko Nakamura sat with her Grade 8 classmates on the floor of her private girls school, listening to a lecture about duty to the emperor. Setsuko and some of her classmates had been training as decoding assistants for the Japanese army, in preparation for the final invasion by Allied forces.

But the Allies didn't invade Hiroshima. At 8:15 a.m., Setsuko saw a blinding blue-white flash out the window; she felt her body fly through the air. When she regained consciousness, the schoolroom had collapsed around her. It was dark as night and silent except for the faint whispers of her classmates: "God help me. Mother, help me!"

She felt a hand on her back and a male voice – a soldier, perhaps – urging her to crawl to safety. She crawled. When she was free of the building, she turned around and saw in the unnatural darkness of morning that her school was on fire, her friends within it. She was 13 1/2 years old.

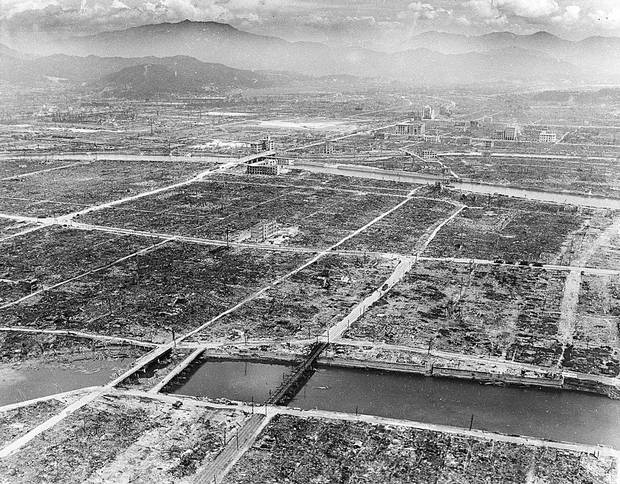

Hiroshima, 1945: Only a few steel and concrete buildings and bridges remain intact in Hiroshima after the Japanese city was hit by an atomic bomb.

MAX DESFOR/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Now, she is 85, her married name is Setsuko Thurlow and she is one of the remaining hibakusha, the survivors of the atomic explosions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. She has lived in Toronto for most of her life, but that morning in Hiroshima is as close as yesterday, both out of choice and necessity.

Necessity, because how could you blot out the destruction of your childhood city, relatives, friends? She has had a choice, all these years, to remain silent, as some survivors did, or to retell her story countless times in the hopes that one day the world would be free of nuclear weapons. She chose the second path. It has been winding and maddening, the promise of disarmament always receding out of sight. But in a final twist, the goal may be a bit closer now, and it's partly because Ms. Thurlow told her story and for once the world listened.

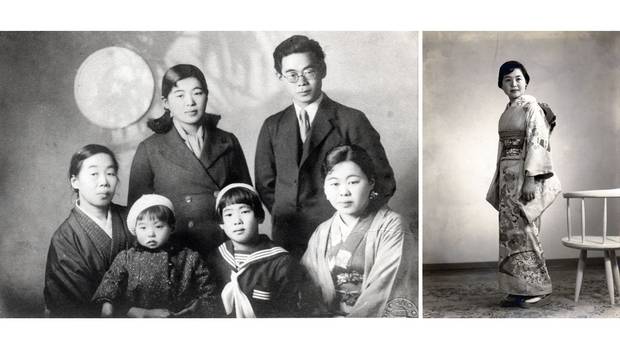

Setsuko Nakamura’s family in their garden in 1935. She is the youngest person in the photo.

PASSAGES TO CANADA DIGITAL ARCHIVE

'I made a vow to my loved ones'

As she sits in her apartment, Ms. Thurlow offers a plate of cherries – "They're very good this year" – and prepares to tell her story one more time. She has not been feeling well; she is drained by recent trips to the United Nations in New York, where she provided testimony that helped bring about a treaty banning nuclear weapons last month. (The treaty is largely symbolic, but its supporters hope it will lead to the eradication of nuclear stockpiles eventually.)

Ms. Thurlow may be tired, but it's the kind of tired that comes after fruitful effort. She is also, it must be said, more than a little annoyed with the disarmament foot-dragging of her birth country, Japan, and her adopted homeland, Canada.

"I feel it's really important to tell my story," she says. "I made a vow to my loved ones, my schoolmates, to family and friends, that their deaths would have significance. It would not be in vain. I would not forget this. I would do my best till my last breath."

More than 70 years later, her voice still shakes with emotion as she remembers the day the bomb exploded 2,000 feet above her city, like "a sheet of sun," in the words of the famous New Yorker article Hiroshima. As she walked away from her school, Ms. Thurlow encountered shapes shuffling through the sooty dimness that were almost unrecognizable as human. Strips of flesh were torn from their bodies. She saw people with eyeballs and intestines hanging out. Yet, no one cried out. To a 13-year-old girl, "the silence was spooky."

For the whole day, she and two classmates tried to help thousands of injured lying in a military training ground. Victims called for water, but the girls had nothing to carry it in, so they soaked the blouses of their uniforms in a nearby stream and pressed the dripping cloth to the mouths of the dying. That night, they sat on a hillside and watched the city burn. Hiroshima had been chosen as a target by the Americans because it was a military and industrial centre, but also because those hillsides would "focus" the effect of the uranium-based atomic weapon. By the end of 1945, as many as 140,000 people would die from the effects of the bomb and another 75,000 from the bomb dropped on Nagasaki three days later.

Her parents had survived the blast and came to retrieve her. But Setsuko's sister and four-year-old nephew, who had been on their way to visit the doctor in the centre of the city, were badly burned. For days the family tended them, while the sister apologized for failing her son and the son cried for water. When they died, soldiers threw their bodies in a pit and set them on fire, turning the bodies with bamboo poles while Setsuko and her parents watched.

It is impossible to imagine how such an event would affect a person. What Ms. Thurlow felt was nothing: complete numbness. And that was the worst feeling of all. She says, "For years I thought, 'What kind of human being am I?' My dear people are being treated not even like human beings and I didn't even feel sadness. I didn't shed a tear."

Left: Setsuko Nakamura’s family before her immigration.

Right: The young Setsuko in a kimono in 1950, before she left Japan for the United States. Photographs like these were typically taken to assist in arranged marriages.

PASSAGES TO CANADA DIGITAL ARCHIVE

Setsuko Thurlow is shown on her wedding day on July 2, 1955, outside the National City Christian Church in Washington, D.C.

PASSAGES TO CANADA DIGITAL ARCHIVE

It took years for Ms. Thurlow to forgive herself and to understand that this numbness was her brain's mechanism for coping with unimaginable trauma. As a way of atoning – though she hardly needed to atone for an act of war she did not commit – she dedicated herself to a life as a disarmament activist.

Part of that work has taken place in Toronto, where she settled with her Canadian husband, Jim, after their marriage in 1955. (They had to marry in Washington, since Virginia, the state in which Ms. Thurlow was studying at university, would not marry whites and non-whites.)

For 20 years, Ms. Thurlow was a social worker with the Toronto District School Board and would share her story with high-school and university students as often as she could, at home and around the world. The path to peace activism was paved with small successes, such as the establishment of Toronto's Peace Garden in 1984 as well as Hiroshima Nagasaki Relived, a disarmament group she founded with her husband (Jim Thurlow died in 2011). She became a member of the Order of Canada in 2007.

But that path, frustratingly, seemed to be leading nowhere – especially in recent years. The issue of nuclear disarmament, which had drawn huge crowds to rallies in the 1980s, seemed to have fallen off the public radar. Disarmament treaties were stalled. Alarmingly, the nine countries that possess nuclear weapons have recently committed to renovating or expanding their arsenals. There are currently about 15,000 nuclear weapons globally, thousands of them ready to be used at a moment's notice and more powerful than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima.

May 27, 2016: Former U.S. president Barack Obama puts his arm around Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe after they laid wreaths in front of a cenotaph at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park.

KIMIMASA MAYAMA/REUTERS

'It's a beginning'

There was no concrete action to reduce stockpiles or take weapons off their hair-trigger launch status, even as international geopolitics grew more precarious and former statesmen such as George Shultz and Mikhail Gorbachev gave dire warnings about the need for nuclear disarmament. Every year, on the anniversary of Hiroshima, Ms. Thurlow would listen to the platitudes of politicians remembering the bombing. Last May, two months before the anniversary, Barack Obama became the first sitting U.S. president to visit the city, saying, "We must change our mindset about war itself."

Every year, Ms. Thurlow grew more tired of the empty words, saving her deepest scorn for the government of Japan: "On Aug. 6, they always make a gesture. They keep repeating meaningless rhetoric. They are liars. I hate to use such language, but they are."

Several years ago, there was an important development: The global disarmament community, deciding that the weapons-owning states weren't living up to their obligations to pursue arms reduction, decided to do an end run around them by focusing on the humanitarian consequences of a conflict. After all, it wouldn't just be the citizens of the nuclear states who would be harmed in such a war, but humans all over the Earth, including many of the poorest. In a series of conferences held by the United Nations, more than 100 countries, as well as NGOs, health advocates and survivors, came together to put together a treaty banning nuclear weapons.

Ms. Thurlow spoke at several of those gatherings, including one in New York in March, where the draft ban treaty was being hammered out – without the participation of Canada, which had boycotted the talks along with the United States, its NATO partners and the nuclear-weapons states. (In 2016, the United States asked its NATO allies to boycott treaty negotiations and all but the Netherlands complied.)

In a choked voice in New York, Ms. Thurlow related again the story of that August day in 1945 – the ghostly legion of survivors, her dying sister and nephew.

"The memories and images of those perished have always supported and guided me," she told the delegates gathered at the UN. "I think this is how many survivors have kept on living – to make sure that the deaths of their loved ones were not in vain."

Her testimony was greeted with sustained applause. "It was very powerful to hear," says Ray Acheson, head of the disarmament advocacy group Reaching Critical Will, who was at the session that day. "A lot of people were in tears." The testimony of Ms. Thurlow and other survivors was important to the negotiations, she says, because "it provided lived experience that can't be denied."

The ban treaty was signed by 122 countries, with the Netherlands voting against it and Singapore abstaining; the ratification process begins in September. Even its most ardent supporters admit that it is only a first step – it has no binding effect on countries that have weapons and none of them is likely to sign. But disarmament advocates hope that a treaty banning the last remaining legal weapon of mass destruction will provide the ethical momentum to banish them to history, one day.

For Ms. Thurlow, the trip to the UN reminded her of a happy moment from her past, and a current disappointment. In 1978, she listened to then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau give a famous (and unpopular to his international allies) speech about "the suffocation" of the nuclear-arms race, a four-pronged approach to disarmament. Mr. Trudeau's son, the current prime minister, has not shown a similar commitment to the issue.

"He didn't make himself very popular, with the Americans especially," Ms. Thurlow says of the senior Trudeau. "But he was gutsy enough to be able to say that at the UN. But this time, his son is hiding behind [U.S. President Donald] Trump. He hasn't said boo," she says of Justin Trudeau.

Ms. Thurlow was present when it was announced that the ban treaty had passed, and amid the cheers and applause, she felt an uncanny sense of disbelief. A familiar numbness. Something good had finally happened, after 70 years. She will carry this feeling with her on Sunday, at the Hiroshima anniversary remembrance in Toronto. There is still much work to be done. She would like Toronto to agree to study the effects of a possible nuclear conflict on its people, for one thing. But at least she feels she hasn't come all this way for no reason.

"Right now is the greatest time for me," she says. "It's a beginning, but it's a very important beginning."

THE NUCLEAR AGE: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL