In March, 2003, British soldiers helped the Americans invade Iraq based on intelligence that a U.K. inquiry said Wednesday was deeply flawed, in pursuit of a threat that didn't exist – and the intervention went 'badly wrong, with consequences to this day.'

The inquiry sifted through documents that paint a clearer picture of how then prime minister Tony Blair and former U.S. president George W. Bush decided the Iraq invasion well in advance. Here is some deeper analysis of what the inquiry's report found.

ANALYSIS

Letters from Tony: 'I will be with you, whatever'

KEVIN LAMARQUE/REUTERS

If there's one standout line in the 6,000 pages of the British government's Iraq inquiry that hammers readers with its importance, it's the first sentence of a note sent from then prime minister Tony Blair to then U.S. president George W. Bush in the summer of 2002: "I will be with you, whatever."

There and then, it can be argued, the leader of the United Kingdom committed his country and its army to follow the American leader on his march to war in Iraq. Much of the fevered debate that followed – about the supposed threat posed by Saddam Hussein and his evasive weapons of mass destruction – can be seen in the light of that July 28, 2002, "Note on Iraq" as posturing.

As several other diplomatic notes declassified by the Iraq inquiry make clear, the decision to invade was privately taken well in advance by the two men whose opinions mattered most.

The context of the "with you, whatever" line is hard to misinterpret, even as the British PM goes on in the same letter to lay out his concerns about a military push to oust Mr. Hussein.

"This is not Kosovo. This is not Afghanistan. This is not even the Gulf War. The military part of this is hazardous," Mr. Blair writes in the note, which is stamped "secret-personal."

A military or political coalition would preferable, to help deal with "unintended consequences" but, Mr. Blair continues, "getting rid of Saddam is the right thing to do."

Mr. Blair finishes the note by suggesting a "strike date" of January or February of 2003, just a few weeks off the eventual March 20, 2003, beginning of the invasion.

Three months later – while the United Nations Security Council was preparing a resolution that would see weapons inspectors return to Iraq – a diplomatic telegram lands on Mr. Blair's desk that reveals how far along Mr. Bush's thinking also was.

"Bush does not believe it's possible to disarm Saddam without eliminating him," says the October, 2002, note sent by the British embassy in Washington. It goes on to relate how, at the end of Mr. Blair's visit to Camp David that month, Mr. Bush seemed to let his guard down in front of a group of British diplomats.

"Bush suddenly said, without prompting, that it was a terrible responsibility to send young men to war; but if this would bring freedom and democracy to the Middle East, the price had to be paid. Future generations would be grateful. As he said this, he became teary-eyed," the note reads.

However, Mr. Blair later worries that the pair are struggling to convince the international community of the need to confront Iraq. "We start from behind. People suspect U.S. motives; don't accept Saddam is a threat; worry it will make us a target," he writes in a heavily redacted memo – even the addressee's name has been removed – written in January, 2003. "Yet the truth is removing Saddam is right; he is a threat; and WMD [weapons of mass destruction] has to be countered. So there is a big job of persuasion."

But the unsealed diplomatic correspondence also reveals how quickly idealism about Iraq was shattered in the wake of the March, 2003, invasion.

A British Royal Marine from 42 Commando fires a Milan wire-guided missile at an Iraqi position on the Al Faw peninsula in southern Iraq on March 21, 2003.

JON MILLS/ASSOCIATED PRESS

By July, 2003 – as violent resistance to the U.S.-British occupation was starting to spread across Iraq – David Manning, the British ambassador to the U.S. wrote to Mr. Blair, prepping him for a video conference with Mr. Bush.

"The signs point to this getting worse not better… we face a crisis of confidence both in Iraq and internationally," Mr. Manning writes. "Have we got enough troops? The U.S. Administration (and our own Ministry of Defence) seem to be arguing that we have. Personally I strongly doubt it. I am not convinced that the Bush White House fully understands what a critical juncture we have reached."

Sir David Manning, shown in Washington in 2005.

MANUEL BALCE CENETA/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Mr. Blair lets his own frustration show in another note to his own staff, dated September, 2004, as post-Saddam Iraq began to look increasingly ungovernable.

"The issue underlying everything is this: have we got the country into a mess and therefore any bad news is our fault; or is Iraq the battleground whose outcome will determine our own security and therefore the bad news is worth it in the end?"

He shouldn't have been surprised that perception of the war had started to sour. "If we win quickly, everyone will be our friend," Mr. Blair forecasts in his initial "Note on Iraq" to Mr. Bush. "If we don't … recriminations will start fast."

Follow me on Twitter: @markmackinnon

Explainer

Everything you wanted to know about the report but were afraid to ask

by Alicja Siekierska in Toronto

Relatives and friends of military personnel killed during the Iraq War embrace as they attend a London news conference on July 6, 2016.

JEFF J MITCHELL/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Seven years after it was initiated, the Iraq Inquiry has finally released its scathing report on the United Kingdom's decision to join the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Here is what you need to know about the inquiry, its findings and why it took so long for the report to be published.

How did the inquiry come about?

For years, former prime minister Tony Blair faced persistent calls to investigate the initiation of the Iraq war. His government's policy was that an inquiry would be conducted, but only when the time was right and troops had been withdrawn.

After Mr. Blair resigned in 2007, calls for an inquiry continued. In 2009, his successor, Gordon Brown, launched the inquiry into the decision-making leading up to the Iraq invasion.

The goal of the inquiry was to answer two questions – whether it was right and necessary to invade Iraq in March 2003, and whether the U.K. could and should have been better prepared for what followed.

The report was published seven years after the inquiry began.

What was the scope of the inquiry?

It looked at the period beginning immediately after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the U.S., through the 2003 invasion and even up to 2009, when British troops left Iraq.

Why did it take so long to be published?

The sheer length of the report – 12 volumes containing 2.6 million words – is part of the reason it took so long. The inquiry was marred by delays and controversies from the beginning.

In 2009, there was a disagreement over how public evidence should be, with Mr. Brown insisting that evidence would be heard in private. That decision was eventually reversed: The first round of public hearings began late in 2009; the last ended in February 2011.

The release date for the report was repeatedly delayed. According to a House of Commons briefing report, one of the main reasons for the delay were arguments over what documents could be included, particularly in relation to communications between Mr. Blair and former U.S. president George W. Bush.

What did the inquiry find?

The inquiry issued a damning indictment of the decision-making leading up to the invasion, saying Iraq was not a threat at the time and that Mr. Blair was too eager to support Mr. Bush.

Among the many conclusions:

- The strategy of containment could have been adapted and continued for some time

- Military action at that time was not a last resort

- British Prime Minister Tony Blair overestimated his ability to influence U.S. decisions on Iraq

- Judgments about the threat posed by Iraq’s alleged weapons of mass destruction were presented with a certainty that was not justified

- Despite explicit warnings, the consequences of the invasion were underestimated

- The planning and preparations for Iraq after Saddam Hussein were wholly inadequate

- The British government failed to achieve its stated objectives

- It is now clear that policy on Iraq was made on the basis of flawed intelligence and assessments. They were not challenged and they should have been

What happens now to Tony Blair?

The report offered a scathing critique of the former prime minister’s decision-making.

However, as cited in the report, the inquiry was not established to investigate criminal offences nor was it equipped to do so.

If the inquiry were to receive credible evidence that criminal offences had been committed, it would be obliged to refer all evidence to investigating authorities. No such evidence was found.

Scottish National Party MP Alex Salmond said in a statement that Mr. Blair “recklessly committed the country to war without collective judgment.”

“There must now be a consideration of what political or legal consequences are appropriate for those responsible,” Mr. Salmond said.

Mr. Blair issued a 20-page statement in response to the report, saying he takes full responsibility for mistakes made in regards to the Iraq war decision, but added “there were no lies, Parliament and cabinet were not misled, there was no ‘secret deal’ with America, intelligence was not falsified and the decision was made in good faith.”

Whether any legal implications will arise in relation to the report is still unclear, but Mr. Blair’s political legacy has certainly been tarnished by the inquiry.

How long is the report?

The Iraq Inquiry's 12-volume, 2.6-million-word report is about five times the length of Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace (about 560,000 words) and more than three times the length of the Bible (about 780,000 words).

JEFF J. MITCHELL/ASSOCIATED PRESS

How much did the inquiry cost?

Up to March 2015, the inquiry had spent £10.4-million ($17.4-million). The costs for the rest of 2015 and 2016 have not yet been released.

Who is Sir John Chilcot?

The inquiry's chairman was a senior civil servant at the Northern Ireland Office before retiring from that post in 1997. However, work did not stop for Sir John: He was a member or chairman of numerous inquiries, including the U.K.'s 2004 Review of the Intelligence on Weapons of Mass Destruction.

The Iraq Inquiry: By the numbers

- 10,375,000 - The cost of the inquiry, in British pounds, up to March, 2015

- 2,578 - The days it took for the report to be released after the inquiry was initially announced on June 15, 2009

- 2,600,000 - Words in the report

- 6,000 - Pages in the report

- 12 - Volumes included in the report

- 150,000 - Documents studied during the inquiry investigation

- 7,000 - Approximate number of documents referenced in the report

- 2 - Times Mr. Blair was interviewed for the inquiry

- 200 - More than 200 British citizens died as a result of the conflict in Iraq, according to Sir John

- 150,000 - An estimate of the number of Iraqi deaths during the conflict

With a report from Paul Waldie

Follow me on Twitter: @alcjawithaj

Verbatim

Tony Blair’s response to the Chilcot report

Tony Blair arrives for a press conference at London’s Admiralty House on July 6.

STEFAN ROUSSEAU/WPA POOL/GETTY IMAGES

The former British prime minister issued a short statement after the report’s release Wednesday before speaking to reporters later in the day. He defended the decision to join the invasion, but apologized and acknowledged the “hostile, protracted and bloody” aftermath.

The intelligence assessments made at the time of going to war turned out to be wrong. The aftermath turned out to be more hostile, protracted and bloody than ever we imagined. For all of this, I express more sorrow, regret and apology than you will ever know. ... The inquiry claims that military action was not a last resort, but it also says that it might have been necessary later. With respect, I didn’t have the option of that delay. I took this decision because I believed it was the right thing to do based upon the information I had and the threats I perceived.

With a report from Reuters

reaction

How families of the fallen responded to the report

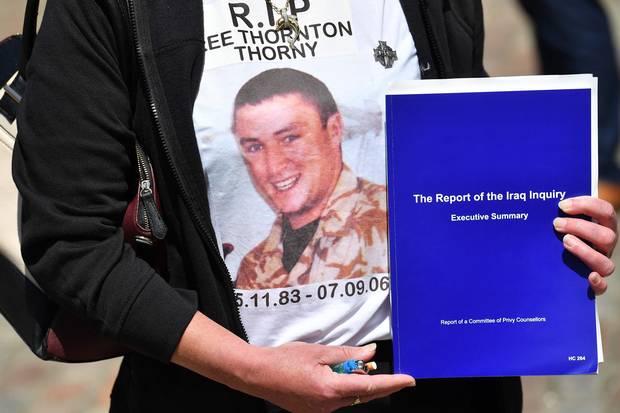

The mother of Gunner Lee Thornton – who died on Sept. 7, 2006, from wounds suffered while fighting in Iraq – holds a summary of the Iraq inquiry report in London on July 6, 2016.

BEN STANSALL/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

“My son died in vain.” –Roger Bacon, who lost his son Major Matthew Bacon during the war

“There’s one terrorist in this world, that the world needs to be aware of, and his name is Tony Blair.” –Sarah O’Connor, whose brother Sergeant Bob O’Connor died in 2005 when the helicopter he was in was shot down over Iraq

With a report from Paul Waldie

ESSAY

Thirteen years later, Iraq still burns – and what have we learned?

by Mark MacKinnon in London

A Iraqi child carrying a sink passes a British tank as they flee Basra, southern Iraq, on March 29, 2003.

ANJA NIEDRINGHAUS/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Sitting in an air-conditioned conference room in the Queen Elizabeth II Centre, with the spires of Westminster Abbey visible out the window, I saw around me some of the faces of 13 years ago.

I saw a colleague with whom I’d once spent a terrifying night sleeping in our cars on a bridge outside the now-infamous Abu Ghraib prison. We were trapped on the highway between Amman and Baghdad as a firefight between the U.S. Army and the remnants of the Fedayeen Saddam blocked our way on the last night before the Iraqi capital capitulated.

I saw another reporter who used to pop by the room I shared with colleagues in the Ishtar Hotel during the chaotic days that came next in April, 2003. The Ishtar, which like most of Iraq had neither air-conditioning nor running water at the time, overlooked Baghdad’s central Firdos Square, where the iconic statue of Saddam Hussein was pulled down as we watched.

All of us had front-row seats in the days that followed, as the mood in the country rapidly slid from hope to anxiety to anger.

A U.S. soldier watches as a statue of Iraq’s president Saddam Hussein falls in central Baghdad on April 9, 2003.

GORAN TOMASEVIC/REUTERS

On Wednesday, we were all in the QE II Centre, pouring over the blunt verdict contained in the 6,000-page report of the British government’s Iraq Inquiry. Meanwhile, 4,000 kilometres away, the country in question, which barely exists anymore as a single entity, continued to burn.

The judgments of the Iraq Inquiry – better known as the Chilcot Inquiry after its chairman, Sir John Chilcot – took seven years to reach. But most of them were obvious to anyone who has been paying even scant attention. The findings will be little salve to the 179 British servicemen, 4,500 U.S. soldiers, and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis who have died as a result of an avoidable conflict that haunts us all still.

The war was unnecessary, the inquiry concluded, after reviewing 150,000 documents and interviewing more than 150 witnesses. It also found that the subsequent occupation of Iraq was poorly planned and managed.

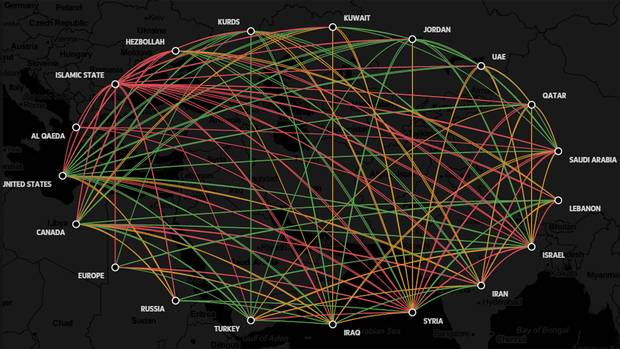

“The evidence is there for all to see. It is an account of an intervention which went badly wrong, with consequences to this day,” Sir John said in a statement shortly after the publication of the report. The inquiry didn’t spell out those consequences, but a short list isn’t hard to conjure: the rise in violent sectarianism across the Middle East; the growth of the so-called Islamic State; the proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran; the ongoing refugee crisis; and the precipitous decline in Western influence around the world.

Then prime minister Tony Blair – taking his lead from U.S. president George W. Bush – was found to have “presented with a certainty that was not justified” the sketchy evidence that Mr. Hussein had an active weapons of mass destruction program.

Former prime minister Tony Blair arrives back at his home after a press conference following the outcome of the Iraq Inquiry report on July 6, 2016.

DAN KITWOOD/GETTY IMAGES

“Peaceful options for disarmament had not been exhausted,” Sir John said of the march to war in 2003. “Military action at that time was not a last resort.” (In reply, Mr. Blair said he “didn’t have the option” of delaying military action. “I believed it was the right thing to do based upon the information I had and the threats I perceived,” he told a press conference in London.)

The inquiry was similarly understated in criticizing the haphazard occupation of Iraq that followed. “The planning and preparations for Iraq after Saddam Hussein were wholly inadequate,” Sir John said. “The [British] government failed to achieve its stated objectives.”

The report is not the “ j’accuse” statement that Britain’s political class had feared. Names are named, but guilt is not assessed. The presumption of good intentions is given to all.

The Chilcot report instead contents itself with drawing up the lessons that should be learned from Britain’s war in Iraq, while admitting that the circumstances that led to war in 2003 “are unlikely to be repeated.”

Mr. Blair is presented as having gone to war largely to preserve Britain’s relationship with the U.S. He appears to have committed the U.K. to war as early as July 28, 2002. “I will be with you, whatever,” he wrote in a letter to Mr. Bush that laid out the challenges of removing Mr. Hussein.

But if Britain went to war to preserve its influence within the Bush Administration, it didn’t succeed. The Chilcot report notes that the U.K. was given little say in – and often completely excluded from – major decisions over the post-war administration of Iraq, including the use of Iraq’s oil revenues, as well as the controversial U.S. decision to fire all former Baath party members from the army and civil service.

On the crucial question of whether the British public was misled about the reason for war via the infamous “dodgy dossier” that portrayed Mr. Hussein as an imminent threat, Mr. Blair receives less blame than the U.K.’s Joint Intelligence Committee.

“The JIC should have made … clear to Mr. Blair” that the gathered intelligence did not conclusively prove that Iraq had an ongoing weapons of mass destruction program, the report concludes.

Perhaps the most damning line in the 12-volume report refers to the damage done to the public’s trust in government by the whole affair. The effort to persuade people of the threat posed by Iraq “has produced a damaging legacy, including undermining trust and confidence in government statements.”

“The lesson is that all aspects of any intervention need to be calculated, debated and challenged with the utmost rigour,” Sir John said in his statement.

So no serious reckoning from the long-awaited report.

A small crowd of protesters gathered outside the conference centre as the inquiry’s findings were released. “Blair must face war crimes trial,” read one banner. That seems further away after the publication of the Chilcot Inquiry’s findings than it was before. Another woman stood alone on the sidewalk holding an Iraqi flag.

A British Iraqi protester holds up an Iraqi flag outside the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre in London on July 6, 2016.

MATT DUNHAM/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Staring out the window, I thought of the faces of 2003 who are no longer here.

I thought of my driver Mohammed – a onetime member of Iraq’s national volleyball team – who cheerfully regaled us with terrifying stories of Saddam’s Iraq as we drove around a country that was already slipping toward civil war. He was at the wheel in 2003 when a crowd that had been cheering our car as we drove through Baghdad’s Sadr City slum suddenly turned on us and began smashing our windows.

When I tried to find Mohammed on a return trip to Baghdad in 2008, I was told to look in his neighbourhood cemetery, which had grown so much in size over the previous five years that it had overtaken what used to be an adjacent playground. I couldn’t find a trace of Mohammed there either.

Residents of a Baghdad neighbourhood dig a fresh plot in the graveyard in 2008.

MARK MacKINNON/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

I thought of my friend Marla Ruzicka, an American aid worker who was killed by a car bomb in 2005 while trying to collect information in Baghdad about the civilian casualties of the war that none of the involved governments seemed interested in amassing. (The report notes that “greater efforts should have been made” by the U.K. government to keep track of the number of civilians killed.)

Mohammed would have laughed at the Chilcot report’s overwrought findings, which will mean nothing on the ground in his country, which is still at war 13 years later. Marla would have been furious that nobody – still – is being held to account.

Follow me on Twitter: @markmackinnon