Who are the smugglers?

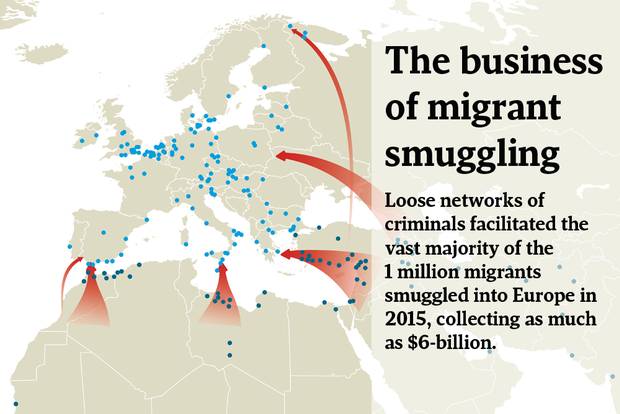

Security officials believe 90 per cent of all human smuggling to Europe takes place with the help of criminal groups. That percentage is expected to increase as the lucrative smuggling routes draws more criminal elements looking to make a profit.

The smugglers are part of a multinational network – and they are as diverse as the very people fleeing conflict, persecution and economic crisis: Smugglers belong to 100 nationalities, often sharing the same country origins as those desperate to get to Europe.

Smugglers are no strangers to criminal activity – and the increasing demand for their services is drawing those already involved with other areas of crime, including drug trafficking, property crime and document forging.

Smuggling networks have a loose structure: Leaders who co-ordinate and control activities along the main routes; organizers who take charge in towns and cities where migrants are transiting and staying; and low-level facilitators that include drivers, scouts and recruiters who promise safe passage for the right price.

Libya's coastline is where thousands put their lives in the hands of smugglers. Libyan smugglers keep migrants in safe houses for days and weeks at a time. Migrants, often suffering from health problems from their journey through the Sahara, have little access to medical aid or food. Some are physically abused. Fishing boats bought by smugglers set off from coastal towns such as Zuwara in early hours of the morning. Those who steer the fishing boats can be incompetent. The sinking of a boat off Libya last April that killed more than 800 people happened in part because the Tunisian captain mistakenly rammed a merchant ship that was attempting to assist them.

How much value is there in the smuggling trade?

On average, refugees and migrants pay between $3,200 (U.S.) and $6,500 for their journey to Europe. Considering that more than one million people attempted to reach Europe in 2015, the average turnover of the smuggling trade is estimated to be between $5-billion and $6-billion.

In 52 per cent of cases, refugees and migrants pay for their journey by cash. An alternative banking system, called Hawala, also a plays an important role and is used to transfer funds to their facilitators. Family relations in Europe are another source of cash – paying the smugglers to get loved ones across borders.

Most of the money pocketed by organized criminal groups is carried across borders – often smuggled in cars – and eventually invested in what appear to be legitimate businesses: car dealerships, grocery stores and real estate. The money often ends up in the myriad countries where smugglers originate, or it ends up in Europe – where many smugglers carry European passports or have residency.

Those trying to get to Europe can often end up in debt which makes them vulnerable to sexual exploitation and slave-like working conditions in which they lack proper access to health care and food. In other cases, they can end up as drug mules – forced to carry drugs across borders.

What is the toll of the smuggling routes?

An estimated 3,279 people travelling in rickety fishing boats and dinghies crammed with passengers died in 2015 trying reach Europe. The overwhelming majority of the deaths, or 77 per cent, took place along the central Mediterranean route. That death toll did not stop the boats pushing off from the Libyan coast for the shores of Europe on a daily basis. The other deaths happened along the most-travelled southeastern Mediterranean route from Turkey to Greece.

In 2016, the number of deaths owing to drowning, illness at sea or inhalation of gas fumes stands at 1,475 as of May 25. The death toll for a similar period last year was 1,828, according to the International Organization for Migration. Deaths in 2016 could still end up exceeding the 2015 toll: There is a crackdown on the southeastern route on smuggling networks in Turkey, and migrants and refugees seek alternatives such as the more deadly central Mediterranean route.

What are the routes?

The most active route in 2015 was the southeastern Mediterranean route, where 885,386 people attempted to cross from Turkey to Greece. That represented a 1,612-per-cent jump compared with the previous year – a massive spike owing, in large part, to Syrian refugees trying to get to Europe. The second-most active route was the central Mediterranean route – drawing 153,946 people, mainly from African countries, trying to cross the dangerous waters. With Turkey cracking down on smuggling networks, the flow of people trying to reach Europe could return to previous patterns with the central Mediterranean route once again overtaking the southeastern Mediterranean route.

Rubber dinghies, eight to 12 metres long, and carrying up to 40 passengers, were the most common means of crossing on the southeastern route. Smugglers seldom get on to the dinghies. Instead, they give instructions to the passengers on how to steer the boats to Greece. Larger fishing boats and vessels are more common on the central Mediterranean route.

Western Mediterranean

In 2015, this route via Spain and Portugal accounted for a total of 7,164 migrant border crossings mainly by Guinean, Algerian and Moroccan nationals. The number of crossings has consistently stayed low compared with other routes since 2008 in large part because of co-operation between Spain and Morocco to stop smuggling networks, according the EU border agency Frontex.

Central Mediterranean

In 2015, a total of 153,946 migrant entries were detected along this route. In 2016, the arrivals stand at around 40,000. A booming smuggling network is using the Libyan coastline and the cover of political unrest to send rickety fishing boats and dinghies in the direction of Europe. Passengers on the boats include young men fleeing indefinite military service or imprisonment in Eritrea, conflict in Somalia and economic deprivation in Nigeria. Migrant arrivals by sea to Italy and their main countries of origin in 2015: Eritrea, 39,162; Nigeria, 22,237; Somalia, 12,433.

Southeastern

Originating from Turkey, refugees and migrants aim to reaching the EU mainly via Greece by sea. The number of those travelling this route increased dramatically in 2015 compared with the previous year, as Syrians and their families fled a brutal civil war in its fifth year and more than 250,000 killed. Syrians accounted for 56 per cent of arrivals. In total, 885,386 entries were recorded in 2015, peaking in October with more than 200,000 arrivals. Although this route is expected to shrink in 2016, as smugglers in Turkey feel the brunt of a crackdown, the current numbers are still high: 156,157 arrivals so far, and Syrians accounting for half.

Eastern route

Refugees and migrants enter the EU along the 6,000-kilometre stretch of external borders with Belarus, Moldova, Ukraine and Russia. In 2015, 1,920 entries were recorded with most of Afghan, Vietnamese or Syrian nationality. That is about 0.2 per cent of the total sea and land arrivals in 2015.

Nordic route

Refugees and migrants travel across Russia to enter the Schengen zone via Norway or Finland. More than 2,000 attempted this route in 2015, including people fleeing Syria, Afghanistan and Pakistan and using bicycles to cross the border. Crossings have taken place even during winter months, when temperatures are well below zero.

Sources: Interpol, Europol, International Organization for Migration, Reuters