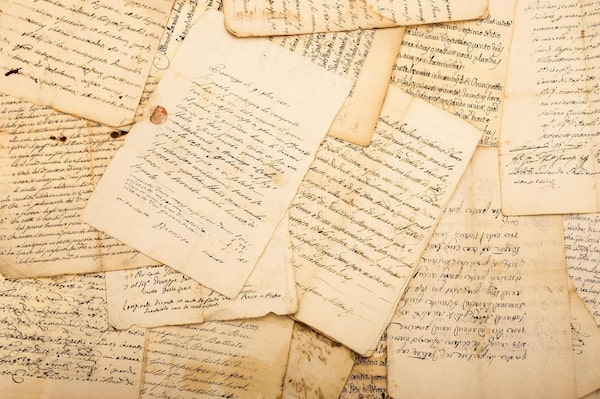

Paul Wright supplies parchment and vellum, a rare writing material, to royal households, governments, universities and religious institutions around the world. His craft, along with an number of other aspects of non-tangible heritage, are on the verge of going extinct, according to a recent study.scisettialfio/Getty Images/iStockphoto

At a time when almost everything is done at top speed, and cellphones and computers are ubiquitous, Paul Wright stands out as a throw-back to an ancient era.

Mr. Wright is one of only two people in Britain who know how to make parchment and vellum, writing material made from animal skins that was used for centuries to record texts such as the Domesday Book, the Magna Carta and the Dead Sea scrolls. He runs a small business northwest of London called William Cowley Ltd., which employs the country's only other parchment maker, and supplies the rare product to royal households, governments, universities and religious institutions around the world that still use it for important documents.

"We're the last of our kind in the U.K., and we're probably the last of our kind in the world," Mr. Wright said from his shop, where making just one sheet of parchment can take three months.

His skills are so rare they are among dozens of ancient crafts that are on the verge of extinction, according to a new study by Britain's Heritage Crafts Association (HCA). The report has raised concern about the growing loss of what is known as non-tangible heritage – rituals, festivals and craft skills, for example. And it comes as the United Nations and other organizations are calling on governments to do more to protect intangible heritage in the same way they preserve historic buildings and artifacts.

Britain has some of the oldest craft industries in the world. Many, such as helmet making, bell founding and sword smithing date back centuries. The HCA report found that of the 169 heritage crafts identified in the country, four have disappeared and 62 are on the verge of extinction or endangered.

The four that have gone are traditional cricket-ball making; "gold beating," which involves pounding the metal into thin strips for gilding; lacrosse-stick making; and manufacturing sieves or riddles, which are a type of sifter. Among the skills close to extinction are making parchment, saws and hat blocks for use in designing hats. The report noted that Britain has just two skilled clog makers, one fan maker, two businesses that make coaches and wagons and only one piano manufacturer.

"It's really sad finding out that things don't exist," said Greta Bertram, an HCA researcher who conducted the study. She said the association will use the list as a baseline for future surveys on the state of craft skills.

The report found a variety of reasons for the decline, including a lack of training opportunities, an aging work force, competition from mass-made products and a lack of government support. It also rejected suggestions these skills are not worth preserving because they are not viable.

"Often people say that people can't earn a living from [these skills] or we don't use these products any more, so why should we keep those skills going? That's a bit ridiculous," Ms. Bertram said. "We don't necessarily expect all of our heritage buildings to justify themselves financially, but we support them and value them as part of our heritage because that's how we view them. We recognize biodiversity as part of our natural heritage and we are concerned about it for that reason. And we're thinking of these craft skills as part of our intangible cultural heritage."

Global focus on intangible assets is increasing. More than 170 countries have signed UNESCO's Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, which was adopted in 2003 and focuses on protecting non-physical aspects of heritage such as performing arts, festivals, rituals and craft skills. Several countries, including Norway, India and Guatemala, have also launched programs to identify and preserve intangible heritage.

Britain, Canada and the United States are among the few countries that have not ratified the convention. Those governments have generally argued that the definition of intangible cultural heritage is vague and that the convention creates onerous obligations. But that is coming under fire from many organizations. The Canadian government has faced increasing calls to ratify the convention, and provincial governments in Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador have introduced laws to protect intangible cultural heritage. Last year, 200 representatives from a range of heritage groups, government organizations, museums and First Nations called on the government to ratify the UNESCO convention. Britain is under similar pressure from the HCA and others.

There are hopeful signs. Crafts such as knitting and carving have soared in popularity in recent years, along with a surge in specialty craft products. That is what got Shane Skelton into saw making.

He had worked as a blacksmith and a gunsmith in Britain and was never impressed with the tools he used. Three years ago, he and his wife, Jacqueline, started Skelton Saws from their house in Scarborough, North Yorkshire. They make saws based on techniques used 300 years ago, producing everything by hand. "A person can send us the size of their hand and we can produce them a saw that fits them perfectly," Mr. Skelton, 39, said from the workshop. It takes up to 25 hours to make one saw, at a cost of about £245 ($398), and more specialized products can take nearly three times as long and cost up to £1,500 (about $2,500).

The Skeltons are the only traditional saw makers in Britain, something Mr. Skelton laments. "There are a lot of people doing all types of very creative things, very old traditional things that probably in another generation won't exist. We're the only saw makers to have set up in over 100 years in England as a traditional maker," he said.

Mr. Wright, 51, is also trying to revive parchment making. He has just launched an internship program at William Cowley and hopes to train someone to take over the business eventually. "It takes so long for someone to be taught the ins and outs of parchment and vellum making. It's a seven-year process," he said, adding that he learned the craft from the previous manager. "It may take a while, but I'll find someone."

Paul Waldie

Paul Waldie