The election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency on a platform devoted largely to themes of ethnic nationalism and racial and religious intolerance was a wake-up call to those of us who believed our ethnic group was largely benign, but for small pockets of zealotry at the margins.

As white people, it was our turn to experience the cold shock of discovering that a significant part of our community has been radicalized, sometimes over the Internet, into a form of intolerant extremism that rejects conventional Western values and threatens the integrity of entire countries. That it has so far manifested itself in ballots rather than bombs shouldn't mask its gravity: Because we are so numerous, our zealots are capable of paralyzing nations.

We need to do what we have long told other groups to do when they face an extremism problem: Speak up about it, identify it, try to understand what has happened to so many people like us, find a way to lead them away from extremism.

His election was the work, almost entirely, of white people. Almost 90 per cent of Americans who voted for Mr. Trump were white, and most white U.S. voters, both men and women, cast a ballot for him (even though his opponent got more votes over all). And at least 90 per cent of non-white Americans did not vote for him. This was a white riot – an angry, rejectionist turn by a deeply pessimistic majority within the white population against the far more hopeful and inclusive politics of the rest of the country.

The scores of white Americans I've met over the past 12 months who eagerly embraced, or at least tolerated and voted for, the politics of Mr. Trump are usually, in many respects, impossible to distinguish from other white people. They tend to be normal, middle-class; the largest Trump-supporting sub-segment of them are, like me, men over 45 with only high-school educations. With a few exceptions, they are not overt racists or far-right zealots. Many of them are otherwise quite uninterested in politics.

But these white people have developed a set of beliefs that have led them to see a sort of strongman nationalist politics of ethnic exclusion as being perfectly acceptable, only two generations after their country fought a global war against that very thing. They see it as acceptable, even welcome, that a president-to-be has promised to ban all Muslims from entering the country ("temporarily"), to mass-deport millions of Latino American families who have been living in the United States for decades, to describe those immigrants as "rapists," to question the citizenship and loyalty of minority Americans.

These white voters, while they don't consider themselves racist, do not see a problem with a president-elect whose only response to black Americans is to speak of violence and moral degradation. Or a commander-in-chief who has not seen fit to disavow the phalanx of white supremacists, neo-Nazis and Ku Klux Klan figures who have accompanied and cheered his campaign.

Or a soon-to-be-inaugurated president whose biggest advertising expenditure was a two-minute November ad in which he describes a global conspiracy of meddling Jews manipulating the economy – an ad that the Anti-Defamation League has denounced as resembling anti-Semitic propaganda.

It is not just an American problem. There is a striking similarity, in lifestyle, geography and beliefs, between those white Americans who voted for Mr. Trump and the white Britons who voted in June to recommend their country's withdrawal from Europe's economy and politics, on what surveys showed were largely xenophobic grounds. They also have much in common with the white French, Dutch and Austrian voters who have turned far-right parties of racial intolerance into significant political forces. It would be naïve to assume that groups of white Canadians are immune to the temptations of extremism, for many of us live in similar communities and circumstances.

"I'm seeing a lot of common trends between the Brexit voters, Trump voters and people supporting the radical right in Europe – in general, we're talking about disaffected white voters with low education levels and a particular set of values," says Matthew Goodwin, a politics professor at the University of Kent and author of several major studies of white voter support for populist and extremist movements.

He's one of a group of scholars who have spent the past few days poring over the U.S. vote statistics to attempt to identify exactly which parts of the white population are falling prey to this sort of extremism. And they are finding a strikingly consistent pattern – though not the one many people expected. Profiling white people who turn to political extremism, it turns out, is not that different from the effort to profile Westerners who are vulnerable to Islamic extremism – and the two communities have some backgrounds in common.

While Trump and Brexit and far-right voters are clearly distinguished by race, not all white people are falling into political extremism: Certain groups appear immune.

The factors that predict Trump support among white people aren't as easy to predict as you may think.

White extremists are not distinguished by geographical region (Trump voters showed up in the South, the north, the Sunbelt and the Midwest).

Nor, despite what a lot of literature predicted, are they distinguished by poverty or unemployment: Most Americans with incomes below $50,000, and a strong majority of people with incomes below $30,000, voted for Hillary Clinton. Mr. Trump got his strongest support from solidly middle-class white people with incomes from $50,000 to $100,000, and also won more support in higher-income groups.

Nor was gender as big an indicator as predicted: While Trump supporters were more likely male than female (which was expected, given his admissions of sexual assault and the fact that his opponent was Ms. Clinton), nevertheless a surprisingly high 42 per cent of American women cast their ballot for Mr. Trump.

If poverty, gender and region don't draw white people into extremism, what does? One factor is size of community: Americans who live in cities of 50,000 or more overwhelmingly voted for Ms. Clinton, by a margin of 59 to 35 per cent. But "small city or rural" residents voted for Mr. Trump by almost the same margin (62 to 34), with the suburbs almost equally split between the two. And the other big predictor, as the scholars noted, was education: White people without post-secondary education voted for Mr. Trump to a huge degree (70 per cent to 30); he also got the most votes from white people with degrees, but only by 4 per cent. And military service is a big predictor: Six veterans and soldiers in every 10 voted Trump (but this has always been true for Republicans).

Those figures might tell you where to look for Trump supporters. But the fact that they're non-poor, rural, less-educated older people does not really tell me what's happening in my ethnic community. It doesn't explain the source of their extremism, the factors that motivated them to take this controversial political leap, what has made them so angry, and what we might do to channel that rage into something less destructive.

For that, I found that I needed to look more deeply into the thoughts and anxieties and lived experiences that are motivating these voters – and spend some time with them.

Three dinners

As it happens, I've met a lot of Americans over the past 12 months who have embraced, or at least given their vote to, the politics of Donald Trump. Sometimes I've sought them out, but often they take me by surprise: friends, relatives, people sitting next to me at cafés or airport gates, little old ladies working shop counters.

Three encounters with white people this year seem to illustrate most vividly some aspect of the phenomenon. All three were over a dinner table, or at least a counter: This form of radicalism was often shy to show its face, at least before the election; a meal was often needed to open people up.

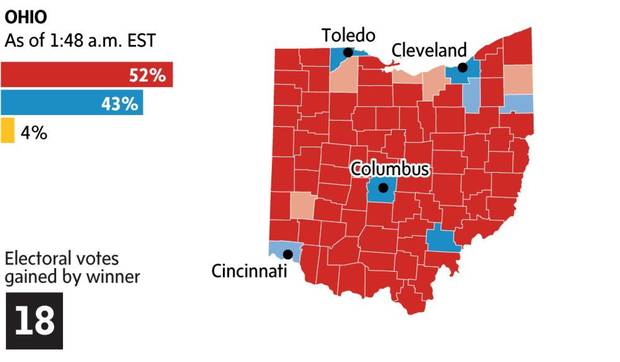

What the map of Ohio looked like the day after the election.

MURAT YÜKSELIR/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, ASSOCIATED PRESS

The first dinner, back in the spring when primary voting was still underway, took place in the eastern suburbs of Cleveland. My companion, who had a beer and a bowl of soup at a sandwich joint, was an affable guy named Burt Weiss, who is in his fifties. He works, at the moment, for the sales department of a pharmaceutical company; it's a series of short-term contracts strung together, so he doesn't get a full pension and only very limited medical benefits. He sometimes drives Uber on weekends for extra income.

He told me he was making, between his income sources, about the same sort of money as his father, who'd had one of those classic old-economy shift jobs in a steel mill. But he has less job security and fewer benefits.

Burt comes close to fitting the stereotypical view of Trump voters as economic victims of a changing economy who are "left behind" by modernization and hit hard by the loss of jobs to technology and China – a profile that doesn't actually suit that many Trump supporters.

Except that he doesn't see it that way: "Let's not kid ourselves, there was nothing great about the kind of job my dad had – it was horrible work that nearly killed him, and I wouldn't wish it on anyone," he said. The Rust Belt's era of deep alienation and poverty ended with the 1990s; people are still in precarious shape, but the Obama-era recovery helped people in Cleveland. It isn't the economy, stupid. It's often something less evident.

What bothered Burt, and made him tell me he was drawn to Donald Trump's then-new message, was the people he believed were changing the world around him, making it less stable. Some of them were white guys like him, who he knew were collecting welfare benefits and grants, which he attributed to Barack Obama's economic-stimulus programs.

But he was especially bothered by the change in complexion in his city. "Look around you, half the signs are in Spanish," he said. "They come in, not even legal, work for cash, and they get help from the government. I don't get any help, and I keep paying more and more for health insurance." He talked about "elites" in Washington more interested in minorities and refugees than in people like him; the idea of giving them citizenship rights appalled him: "They're getting a free ride into the middle class when I have to work for it," he said. He didn't personally know any Central Americans, but he felt drawn to Mr. Trump's bid to solve the problem through mass explusion.

"This doesn't feel like my country any more," he said – a phrase I kept hearing from Trump supporters. He liked Trump, he said, because he could restore the United States of his childhood. Things, he said, had kept getting worse, and he wanted someone to fix them.

Indeed, one of the strongest indicators of Trump support (and support for far-right movements elsewhere) is a belief that things were better in the past. A much-discussed survey by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) found that 72 per cent of Trump voters felt that life and culture had been better in the 1950s – a time before civil rights and racial equality. Conversely, 70 per cent of Clinton voters felt things had improved since then. Those results were borne out on election night: Exit polls showed that 90 per cent of Clinton voters felt the country had gone in "generally the right direction"; only 8 per cent of Trump voters did.

And that sense of decline and pessimism is strictly a white phenomenon: Among racial minorities, six people in 10 feel that life has improved since the 1950s, as do people with postsecondary education. The belief that a golden age once existed, but has been trammelled and despoiled by racially different people, is a classic indicator of authoritarian instinct and susceptibility to extremism.

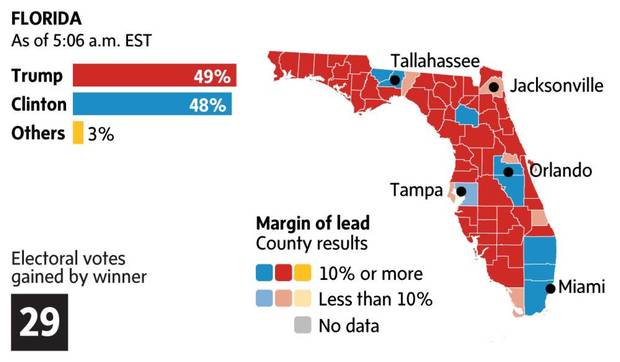

What the map of Florida looked like the day after the election.

MURAT YÜKSELIR/THE GLOBE AND MAIL, ASSOCIATED PRESS

The second dinner took place a month before the election. I met Alice – a successful businesswoman, who lives in one of the Florida beachside communities that stretch north from St. Petersburg – for dinner with her two young-adult sons. An educated and worldly woman, she has friends and associates of every race and religion, and her husband is an immigrant from a non-English-speaking family.

But, she said, she was terrified of the prospect of rising crime brought by "all the refugees and immigrants they're bringing in here," people she felt would strain the health-care system and bring down property values. (Florida has a lot of foreign-born citizens, especially from Cuba and Mexico, but they don't have higher crime rates.) Although her neighbourhood, which is gated and predominantly white, does not see much crime, her family had armed up, accumulating more firearms to protect itself. They spoke favourably of Donald Trump's management acumen, and his ability to close the border and fix things.

As we bade farewell, Alice and one of her sons recoiled in alarm when I told them that I'd be driving back to my hotel in Ybor City, the traditionally Hispanic quarter of Tampa (and, since the 1990s, a popular entertainment district for young professionals).

"You'd better watch yourself – I wouldn't go anywhere near there," she said. It was the source of fear, the inner-city "hell" of Donald Trump's speeches. That Ybor City has become an upwardly mobile place has escaped notice. (It was also, not coincidentally, the site of peaceful anti-Trump protests this week.)

Her anxieties fall into one of the biggest mysteries of far-right support among white people: the phenomenon that has traditionally been called the "halo effect."

By contrast, white people who live in areas where they're immersed in longstanding populations of immigrants and minorities – that is, in big cities – don't generally tend to vote for the politics of racial intolerance. That's called the "contact effect" – you don't get anxious about immigration if you live around immigrants. But people who live in mainly white areas that adjoin cities with greater diversity often show very high levels of support for people like Mr. Trump.

"The general consensus in the literature is that you get the strong anti-immigration sentiment when you have a relatively low local share of minorities and immigrants coupled with a high rate of change," says Eric Kaufmann, a professor of politics at the University of London and author of The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America: The Decline of Dominant Ethnicity in the United States. "That is, if you live in a very white area but you're close to an increasingly diverse area."

Prof. Goodwin has also noted that white people in areas with sudden changes in immigration numbers grow intolerant at first, then become more tolerant after a few years, when the contact effect has been able to kick in.

In other words, proximity is a bigger driver of extremism than is actual experience: It is not economic decline or immigration that cause people to become right-wing radicals, but proximity to those things, from a vantage of white security that feels threatened by the unknown.

Donald Trump holds up a mask of himself at the Sarasota Fairgrounds in Sarasota, Fla., on Nov. 7, 2016.

LOREN ELLIOTT/THE TAMPA BAY TIMES/ASSOCIATED PRESS

My third dinner occurred on Wednesday, the night after the election, at a steakhouse in an upscale shopping mall in a well-off corner of Sarasota. Four white couples, two of them middle-aged and two in their thirties, gathered around me for their traditional weekly meal out, in nice jeans and button-down shirts and summer dresses. From their relatively un-celebratory tone, I assumed that at least some of them were Democrats, until one of the guys asked the waitress to take CNN off the overhead TV and replace it with Fox News. The other three couples piped up in jovial agreement: "Yeah, CNN sucks," said Robin, the youngest of the guys.

They'd all voted Trump the day before; in fact, it was hard to find anyone in the joint who hadn't. And, if you asked, they were pleased with the result. "Finally," said Sarah, Robin's wife, "we can start to get this country back to normal." But you had to ask: None of them regarded the election, or its outcome, as a major event; it was a simple resetting, and they'd moved on.

When I inquired more, they said something that amplified what Burt Weiss had told me in Cleveland: They thought things had gotten worse, that their country had gone off the rails. But, specifically, they all agreed that too much had been changed, too fast.

"Obama seemed okay, but then he started really imposing his agenda on the country like crazy, with amnesty [proposed for millions of undocumented immigrants] and health care and all the cultural stuff," said Calvin, one of the middle-aged men. "It was too radical an agenda. If Hillary had won, we wouldn't be able to recognize America any more."

This sentiment – also one I'd heard a lot at rallies and in Republican campaign offices – is what many scholars regard as a key identifier of an extremism-tolerant psychology: a belief that social and political change – even if it is broadly beneficial – is to be feared and resisted, and that order, stability and authority are crucial to comfort and security. Combine that with a sense of threatened ethnic identity and membership in a lower-education voting group, and you have what Prof. Kaufmann and other scholars describe as the most potent recipe for support of authoritarianism.

"What we're looking at is that part of the white population that prefers stability and order to novelty and change; that identifies with an ethnic conception of the nation tied to their own ethnic group; when you've got people with less university degrees supporting these groups, they tend to be getting a lot of support from those places," Prof. Kaufmann says.

"That, much more than anything having to do with economic circumstances, is what we really see as the driver behind Trump and Brexit and those other movements."

The psychology of wounded privilege

Before Mr. Trump's big victory, there were two very popular theories, built on two very influential books, that were most often trotted out to explain why white Americans were voting for far-right figures.

The first was the one proposed by the left-wing writer Thomas Frank in his 2004 book, What's the Matter With Kansas, which argued that both political parties had abandoned the economic interests of blue-collar Americans in favour of cultural politics: Democrats focused on identity politics, abortion, same-sex rights and building a "big tent" multi-ethnic constituency; Republicans turned against "Washington elites," and wanted to restore "traditional values." Both parties promoted a free-market economy that harmed working-class interests. In this view, white voters had been distracted away from their dealing with their own economic concerns by a politics devoted to scapegoating minorities and immigrants.

The second appeared in the more recent bestseller, Hillbilly Elegy, by conservative author J.D. Vance, which describes poor working-class white communities (such as that of his own Appalachian family) as having become dependent on the state and unable to free themselves from this dependence because they've come to believe in a form of racially tinged conspiracy politics that blames anyone but themselves.

Both works note correctly that the white community has come to view mythic "elites" as the major threat to them, a view that drove Donald Trump (and other conservative political movements) to win them over. But both books were shown by Mr. Trump's victory to be somewhat misleading. In Mr. Vance's case, the author himself proved to be much more typical of the Trump movement than the people he chronicled: It was the angry white voters who resent the hillbillies – people like Burt Weiss – not the hillbillies themselves, who flocked to the Republican candidate. And contrary to Mr. Frank, the radical turn against racial minorities did not turn out to be a distraction from liberal economics; instead, Mr. Trump packaged protectionist, anti-trade messages with closed-border messages of nativism, making the economic and the ethnic equal parts of a far-right, isolationist agenda that captured the interest of a great many blue-collar and middle-class voters, as long as they were white.

What is the mindset behind this rejection of the outside world?

Trump supporters cheer as they watch election returns at a rally in New York on Nov. 9, 2016.

EVAN VUCCI/ASSOCIATED PRESS

The propensity of white people to turn to radicalization does seem to be much more rooted in deep psychological anxieties than in anything material or economic.

"It all largely comes under the rubric of cultural and social identity motivations, and not personal economic circumstances – the notion of the 'left behind' voter is quite flawed in my mind," says Prof. Kaufmann.

What is particularly surprising is that the personal circumstances of most Trump voters have improved during recent years: His movement is not a knee-jerk reaction to an actual economic setback (which would have been more the case in 2008 or 1980, when different sorts of U.S. politics prevailed). Rather, it is based on a deeper psychic sense of loss, one not so solidly moored in lived reality.

Carol Anderson, a historian at Atlanta's Emory University who recently published the book-length study, White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of our Racial Divide, sees the turn toward Trumpian extremism as a psychological response among many white people not to any actual loss – the Trump voters are typically more well-off people, who have gained in recent years – but to a sense of relative loss of influence caused by the increasingly equal status of black and brown Americans.

"When you're talking about the angst and anxiety and feeling of being stifled and that kind of despair, what I see is that, as African-Americans advance in this society in terms of gaining their citizenship rights, that there is a wave of what I've been calling 'white rage,' which are the movements within legislative bodies and within the judicial sector in terms of policies and laws and rulings that undercut that advancement," Prof. Anderson said during a panel last month organized by the online publication, Politico.

"You know, if you've always been privileged, equality begins to look like oppression," she said, in what may be the most definitive phrase to describe the crisis of white extremism. "That's part of what you're seeing in terms of the [white] pessimism, particularly when the system gets defined as a zero-sum game – that you can only gain at somebody else's loss."

Of course, the American experience has not been zero-sum: The inclusion of minorities and immigrant groups into the middle-class economy over the last five decades has not diminished living standards or earnings; they're better than they were in the 1950s. Trade with Mexico and China did hurt employment in the 1990s, but it is not doing so today; the economic precariousness of the Rust Belt is caused by technological change, not by trade or immigrants.

But a psychology of wounded ethnic pride – and often of wounded virility – has overtaken a large part of the white community, and not generally the part that is actually feeling economic pain. If those of us worried about the extremists in our midst want to root them out and turn them around, we need to speak to this underlying sense of loss. It may not be rational or realistic, but it has become profound enough that it has provoked the most extreme and dangerous political event of the century.

Draining the swamp

How, then, do we defuse it? Most scholars feel that the portion of the white community susceptible to extremism has been around for at least a decade and a half; it was simply waiting for someone like Mr. Trump to channel its anxieties into ethnic and foreign scapegoats, as Mr. Trump has done to an extent nobody had previously believed possible.

But a politics of racial demagoguery was by no means the inevitable outcome to this moment of emotional displacement among less-educated, more segregated branches of the white community. Nor is it something that has to be tolerated.

It is clear that economic solutions to the actual crises of the postindustrial white working class, however desirable they may be in their own right, are not going to solve the crisis of radicalization, which is rooted far more deeply in perception and context than in reality.

It might be worth facing the problem directly: If the strongest predictors of white radicalization are a lack of postsecondary education and residence in an ethnically segregated non-urban community, it's worth thinking of reducing the number of people who live this way. Increasing the proportion of adults with university or college educations is both economically sensible – since this is where the middle-class incomes are found – and also politically wise. Canada has a considerably higher rate of postsecondary education than the United States, and it may be one reason why these currents of intolerant racial politics have not washed up here significantly.

Likewise, creating less-segregated, higher-population-density urban and suburban districts is a good idea in its own right, both ecologically and in planning terms (it makes public transit possible, for example); if it cuts down on pockets of racial intolerance, then it is doubly worth pursuing.

On the other hand, Prof. Kaufmann suggests that the language of mainstream politics needs to change. If conventional liberal and conservative parties want to win those numerous angry white voters back from extremists like Donald Trump, he says, they'll need to start talking about our plural society differently.

"I'm interested in how reframing the language of national identity can have an effect," he says. Instead of celebrating "diversity" as a virtue in itself, it may be better to focus on the other side of the immigration coin, the near-universal tendency of newcomers to adopt universal values, to become part of mainstream society, to intermarry, to become normal people.

"I think if you actually speak directly to the ethnic majority and their anxieties – if you point out the degree of assimilation that's occurring, the extent to which people are becoming more like each other and their children are becoming just normal Americans, then white people may begin to see them as something other than a threat."

After all, the tragedy this week was not just that a radical faction within the white community broke away from the rest of the United States and elected an extremist, but that they abandoned the Democratic and Republican parties in the process, leaving mainstream politics without a language that can lead to victory.

If they want to end this nightmare, they will need to find a way to reach 60 million radicalized white people and find words that can bring them back to earth.

Doug Saunders is The Globe and Mail's international affairs columnist.

Follow him on Twitter: @DougSaunders

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The economic impact of Donald Trump’s election victory

2:12