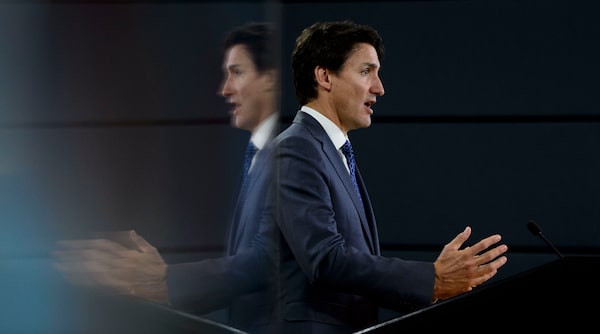

About 64 per cent of Canadians voted for the group of centre-left parties that will be asked to hold Justin Trudeau’s minority government together.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

After an ugly and divisive year, it’s time for Canadians, and their government, to stand up, shake off the dust and look beyond the immediate horizon.

About 64 per cent of Canadians voted for the group of centre-left parties that will be asked to hold Justin Trudeau’s minority government together. For Liberals, it will be tempting to do things to appeal to some part of the other 36 per cent.

Yes, Canada will have a national government that has no MPs in Alberta and Saskatchewan, is at war with several provincial governments, has a leader whose image is tarnished and relies on the support of opposition parties. None of this is new or unusual for Canadian governments, though. It might be called Canada’s default configuration.

There is another way to treat such a political moment: as a time to look beyond immediate partisan interests and make some badly needed changes to Canada’s underpinnings, and a time to use a governing consensus supported by almost two-thirds of voters to make investments supported by multiple parties and lasting far beyond the next election cycle.

Some of Canada’s most fruitful periods of forward-looking policy have occurred during eras of minority government – almost all of the ambitious 1960s, a couple of fruitful years in the 1970s, the middle years of the 2000s, times when MPs from multiple parties have been forced to negotiate around issues larger than their own partisan perspectives. Many of Canada’s signature policies – universal medicare and most of the social safety net, the points-based immigration system, the modern pension system, Canada’s largest inflation-adjusted investment in affordable housing, access to information, marriage equality – were the products of minority governments.

This is a good time for Canadians. The economy and incomes are growing; there is nearly full employment; living standards are rising and poverty falling. This election showed that Canada has little political risk of intolerant nationalism.

But this success rests on an unsteady foundation. A big part of Canada’s economy is still dependent on the extraction of scarce resources. It has an aging, only modestly growing population whose shortage of people of income-generating age will make the 2030s and 2040s an extremely expensive and restrictive time for governments and the private sector. The proportion of women in the work force has not grown for 15 years. Canada has a dire shortage of housing supply that has made a home all but unaffordable in major cities – and an existing housing stock, overly dependent on isolated single-family houses, that is both wasteful of energy and ill-suited to building tight-knit communities. Canada’s transportation infrastructure is unsustainably energy inefficient, lacking in capacity and a poor fit for a modern economy.

And Canada has barely grappled with the long-term problems of a changing climate – not just the fiscal cost of shifting to a carbon-neutral economy (despite impressive policy packages offered by the parties likely to govern together), but the even larger cost of adapting and protecting cities and rural areas. Fighting climate change is going to be very expensive, and it will get more expensive the longer we put it off. A study published last month by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities found that protecting cities against modest climate change alone will cost $5.3-billion a year through the foreseeable future.

But that study pointed to one hopeful side of those multiple challenges: many have shared solutions. Investing in green infrastructure is part of a larger, badly needed investment in infrastructure and housing to reduce inefficiency and inequality and support a larger population. Canada’s major cities will hold nearly twice their current population by the end of this century even if immigration rates remain modest, and groups ranging from the right-wing Fraser Institute to the Liberal government’s council of economic advisers have called for a larger population increase, to perhaps 100 million.

A report released this week by the Century Initiative – a group of academic and business leaders who support that target – analyzed the investments and planning decisions that would be necessary to make sure a larger population is an aid to ecological sustainability, economic growth and quality of life, rather than a hindrance.

Those investments include better family and child-care policy, support for cities that increase in density by adding housing to existing neighbourhoods rather than in sprawling across the land, strategies to get Indigenous nations, retirees and under-represented populations a bigger role in the economy, a big expansion of knowledge centres surrounding universities and a plan to expand the capacity of the cities of the North.

They are, as I’ve argued elsewhere, things that we need to be doing anyway – even if the population doesn’t increase – to make the country an affordable, sustainable, inventive place for the next generation. They’re the sorts of policies that repay their investment many times over. And they’re broadly backed by all of Canada’s major political parties. This is a moment to bring them together.

Doug Saunders, The Globe’s international-affairs columnist, is currently a Richard von Weizsaecker Fellow of the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin.

Doug Saunders

Doug Saunders