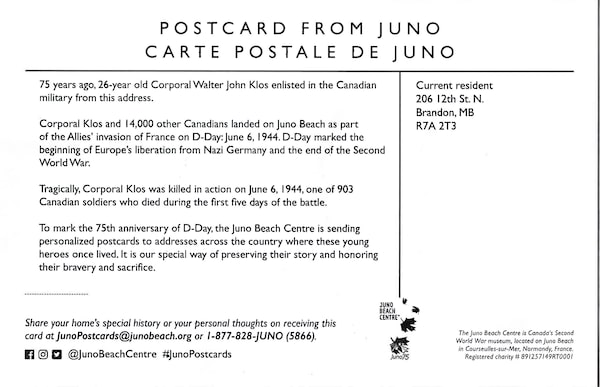

Front side of postcards sent by the Juno Beach Centre to mark the 75th anniversary of D-Day. The postcards were mailed to 355 Canadian homes and inform the current occupants that someone living at their address had enlisted during the Second World War and died during the first five days of the Normandy campaign.Source: Juno Beach Centre

Murray MacLeod felt uneasy. He was a 25-year-old Nova Scotian, the youngest officer of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, but already holding the rank of major.

The mantle of military leadership hadn’t shielded him from harbouring apprehensions. In the hours before D-Day, June 6, 1944, when he would jump into occupied France, he had a hunch he might not survive.

I thought about him recently as I read about the 75th anniversary of the Normandy landing. He was among the first Canadians killed that day when paratroopers under his command tried to destroy a German gun in the village of Varaville.

It was that glimpse of humanity that caught my attention. He overcame his fears and did his duty at the cost of his life. No medal or citation mark his last moments.

His name appears on a list sent to me by the Juno Beach Centre, the museum that honours Canada’s role in the Normandy campaign. The centre has mailed postcards to the former homes of 355 Canadian servicemen killed in Normandy between June 6 and June 10, 1944.

The postcards inform the current occupants that someone who lived at their address died during the first five days of the Normandy campaign. “It is our special way of preserving their story and honoring their bravery and sacrifice,” the cards say.

Maj. MacLeod, from Marsh Street in New Glasgow, was a bank clerk, fourth of the six children of a coal miner. His aunt and uncle raised him after his mother died when he was 8.

The account of his anxieties comes from a fellow officer, Captain Peter Griffin, in an interview for Cornelius Ryan’s book The Longest Day.

In a part that wasn’t used in the book, Capt. Griffin said Maj. MacLeod was a gentle chap who never swore and “had a premonition he was going to get it.”

The night before, he sat on his kit, writing to his Aunt Jessie. “He just felt the need to talk to someone.”

For decades, Capt. Griffin’s interview sat in Folder 22, Box 24 of Mr. Ryan’s papers, stored at Ohio University Libraries. I learned of the archive’s existence from a Toronto man, Geoff Osborne, who has been documenting his grandfather’s military journey.

Mr. Ryan’s book was adapted into a Hollywood epic, in which the most visible Canadian was Paul Anka – playing an American.

More recently, awareness of D-Day was shaped by Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan and the TV series Band of Brothers, with their more gut-wrenching portrayal of combat.

Those productions include nothing about Canadians. Yet, I don’t know what could be more gut-wrenching than, say, the story of Corporal Walter Klos, also on the postcards list.

Like Maj. MacLeod, Cpl. Klos is not a household name, even though some Canadian history books and websites mention his last moments.

He was 26, of Polish ancestry, one of eight siblings who grew up on 12th Street North in Brandon, Man. After Grade 8, he worked at a meat-packing plant. He landed on D-Day with the Royal Winnipeg Rifles.

Jim Parks, who served in the same regiment, told me Cpl. Klos was known by the nickname Bull because he was a sturdy fellow who excelled in tug-of-war contests.

His cause of death is listed as “died of wounds received in action.” What happened, Mr. Parks said, is that Cpl. Klos, despite being injured, charged into an enemy pillbox. They found his body with his hands clenched around the neck of a dead German soldier.

Cpl. Klos’s actions are not commemorated by a medal or a citation. They were the unheralded bravery of the 14,000 Canadians who landed on D-Day.

Back side of the postcard sent by the Juno Beach Centre to "Current resident" of 206 12th St. N., Brandon, Manitoba, the former address of Corporal Walter John Klos. One of 355 postcards mailed to Canadian homes as part of the Postcard from Juno campaign marking the 75th anniversary of D-Day.Source: Juno Beach Centre

The premise of Saving Private Ryan, in which a family loses several sons, befell Canadians, too.

Two of the postcards are addressed to the same Toronto house on Wallace Avenue, home of the Reed family. Philip Reed and his three sons, Gordon, Douglas and Ross, all served overseas.

The brothers wanted to be in the same unit, but officials kept only Douglas and Ross together, to prevent all three from being killed at the same time.

Douglas, a 26-year-old rifleman, and Gordon, a 23-year-old lance corporal, were in the same platoon of the Queen’s Own Rifles regiment. They died with the first wave on Juno Beach. Gordon had just got engaged to a Red Cross nurse.

Another platoon member, Rolph Jackson, told the family that Douglas was hit as he stood before him when the ramp of their landing craft came down, thus sparing Mr. Jackson. Seven of their section’s 10 men died.

Ross survived the war. His son is known as Gord Reed, but his full name is Gordon Douglas Reed, in honour of his uncles. “My dad always felt bad about allowing them to be together. He thought he should have been the one to go,” Gord Reed told me.

Two days after the D-Day landing, the postcard list shows, the brothers Robert and Ronald Northmore of Lansdowne Street in Kingston both died in combat. They enlisted the same day and were issued consecutive service numbers.

Another family that paid a high price was the Rousseaus of Saint-Jean-Baptiste Street in Montmagny, downriver from Quebec City.

Philippe and Maurice Rousseau were among the 14 children of an electrical entrepreneur. The brothers became officers with the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, but Maurice was seconded to the Special Air Service (SAS), the forerunner of today’s British special forces.

Philippe, a 23-year-old lieutenant, jumped with a stick of airborne soldiers in the early hours of June 6. French villagers later wrote to his family to say they had found the remains of two Canadian paratroopers on a road outside Gonneville-sur-Mer.

One body was badly burned, apparently after the ordnance the trooper carried blew up. The other was Philippe. The villagers believe he died trying to rescue his colleague.

The locals began to bury the two Canadians, but were interrupted by Germans who kicked at the bodies, said one letter.

Three months after Philippe’s death, Maurice, a 25-year-old lieutenant, parachuted with an SAS team behind enemy lines in France’s Lorraine region to link up with the local resistance and carry out sabotage operations.

A village priest later told the Rousseau family that Maurice had stayed in his church. At one point, a German officer wanted to be billeted in the presbytery and asked to see the room where Maurice hid. The priest opened the door only partway, the German took a peek, then left without noticing Maurice inside.

Maurice died around Sept. 20, 1944, in a gunfight near Igney, a township in northeastern France. He was protecting his men, a nephew told me.

The nephew, Philippe, is named in honour of his uncle who died in Normandy.

Lieutenants Philippe and Maurice Rousseau, 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, at a transit camp near Down Ampney, England, 13 February 1944. Both officers were later killed in action, Philippe in June 1944 and Maurice in September 1944.Source: Library and Archives Canada

More recent conflicts have garnered ambivalent public reaction, because they were wars with ambiguous aims, with no clear ending, against an enemy wearing no uniform and in battlefields with no front lines.

But even with the moral clarity of the Second World War, the stories of men such as Cpl. Klos or the Reed brothers or Maj. MacLeod have made little impact on the public consciousness.

In 1944, their deaths did not stand out amid scores of casualties regularly reported in newspapers. Today, details of their heroism has to be teased out of old library books, yellowed files, history websites or the memory of family members.

Like the other soldiers’ relatives I spoke with, the younger Mr. Rousseau was grateful for the postcards project. He said to me that we could never talk too much about men who died saving us from Nazism.

Tu Thanh Ha

Tu Thanh Ha