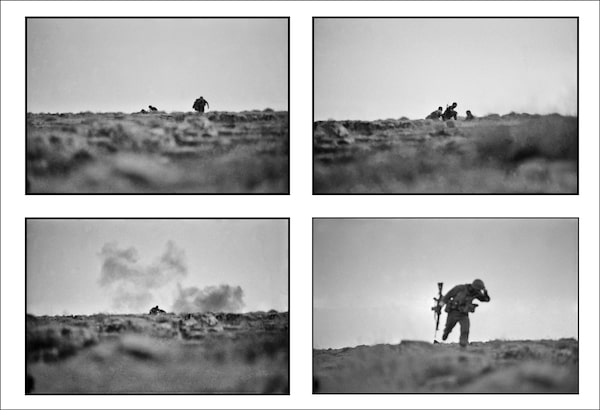

Iranian revolutionary guards celebrate their victory over Iraqi troops Jan. 24, 1987 in Bovarian Island, Iraq.ERIC FEFERBERG/AFP via Getty Images

In September, 1980, hundreds of tanks and thousands of soldiers charged across the eastern border of Iran while Saddam Hussein’s Soviet-supplied jets attacked airfields. Iran’s year-old theocratic regime would soon fire back with “human waves” of tens of thousands of young men and children, who were sent marching across minefields and into machine-gun fire; by 1982, Mr. Hussein would be killing tens of thousands of Iranians and Iraqis with mustard gas, and then nerve gas.

After eight years of total warfare whose forms of brutality had not been seen since the First World War, the Iran-Iraq war would end with nothing gained by either side. More than half a million young men died. Its grisly aftermath would shape almost everything about the future life of Iran and Iraq, and also of the United States, whose entanglements with both countries would shape its political and military life for decades.

We saw that four decades later, in the early days of 2020, when the U.S. assassinated a man considered by most Iranians to be a hero of that war, General Qassem Soleimani. He was in Baghdad, where his Quds Force, created during the Iran-Iraq war to back non-state militias in other countries, had been working for years to ensure Iran’s dominance of Iraq’s post-U.S.-occupation politics.

The Iran-Iraq war was the result of two competing claims to regional dominance.Kaveh Kazemi/Getty Images

Tehran responded Wednesday by firing missiles into Iraqi bases housing U.S. troops, but has so far been careful to avoid a military escalation or American deaths. And whatever led to the deaths of the many Canadians and Iranians aboard UIA Flight 752, it’s clear the Iranian regime does not want to claim that horror as a military act or a response. What its leaders know – and U.S. President Donald Trump does not appear to – are the Iranian lessons from that eight-year war.

First, Iran’s Islamic regime, whose hold on power has always been weak, learned it has far wider domestic popularity when there is an enemy seen to be attacking Iran’s national standing and dignity. Yet, it also learned that it can become the major regional power if it can avoid outright military confrontations with major powers and the unpopular economic hardships that come with them.

The Iran-Iraq war was the result of two competing claims to regional dominance. Mr. Hussein’s Ba’ath Party wanted to be the centre of an ethnic-Arab nationalism across the Middle East; the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini wanted to be the centre of a religious-Islamic nationalism.

An Iranian boy stands on the ruins of his house in Ahvaz destroyed by an Iraqi air raid as the Iran-Iraq war continues on Jan. 25, 1987.ERIC FEFERBERG/AFP via Getty Images

Mr. Hussein’s lesson from the war came in its early months: His real enemy, he concluded, was his own people. He slaughtered Iraqis by the thousands – for being disloyal or ineffective, but especially for being members of any ethnic group he saw as unpatriotic. He used poison gas to kill at least 100,000 Iraqi Kurds just for being Kurdish. In 1991, in revenge for losing the Persian Gulf War, he killed perhaps another 100,000 Iraqi Shiites and Kurds.

Mr. Hussein – who accumulated the worst record for mass civilian slaughter since Pol Pot, and posed a constant risk of committing a third genocide or invading another country – spent the 1990s and early 2000s under United Nations sanctions over his chemical weapons. There was bound to be international military action against him at some point – but the U.S.-led one in 2003, whose postwar occupation was catastrophically botched, was almost perfectly calibrated to strengthen Iran’s hand.

Iran’s regime also spent the 1990s in trouble, but worked to avoid Iraq’s fate. The war had devastated Iranians and destroyed their trust in the government. Its cities are dominated by sprawling war graveyards speckled with photos of young boys. Every family suffered losses, and the economy collapsed.

Coffins are carried on trailers through Tehran on Feb. 19 as thousands watch the funeral service of some 3,000 Iranian soldiers killed during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war, of whom the remains have only recently been recovered.LAURENT MAILLARD/AFP via Getty Images

Iran’s only real reformist leader, Mohammad Khatami, was allowed to be elected in 1997. He seemed to tolerate a huge student protest movement against the regime, on the scale of the one that had brought it to power in 1979 – until a Revolutionary Guard general, that same Qassem Soleimani, publicly told him he’d face brutal punishment if he didn’t quash it. (The Quds Force is not only a threat to other countries.)

Iran has faced more large-scale uprisings, notably the one violently crushed in 2009 – but the hardliners, remembering the war’s lessons, have managed to gain back power and legitimacy by portraying U.S. sanctions as a common threat.

The 2015 six-country peace agreement with Iran showed a sophisticated understanding of those lessons on the part of the Obama administration. They realized Iran’s regime would, and did, prove itself a non-nuclear power if in exchange they could have peaceful and economically beneficial relations with the world. A non-bunkered Iran had a far greater chance of domestic change, and citizens began to speak up.

By both pulling out of that agreement and then launching an attack that rallied a great many Iranians around their autocratic government, Mr. Trump discovered too late that the 1980 war is not yet really over.

Doug Saunders, The Globe and Mail’s international-affairs columnist, is currently a Richard von Weizsaecker Fellow of the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin.

Doug Saunders

Doug Saunders