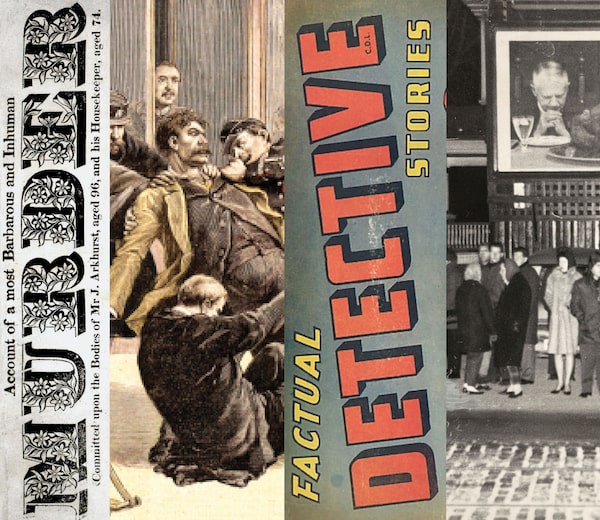

From the left: Justice Comics No. 9, FBI in Action, June 1, 1948; Detail from the dust jacket of Truman Capote’s novel In Cold Blood, 1966; Zac Efron stars as murderer Ted Bundy in the biopic Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, 2019. Japanese version of the True Crime video game, Street of L.A. edition, 2003.

Jana G. Pruden is a Globe and Mail feature writer. This is an adapted version of a speech given at the Lougheed College Lecture Series at the University of Alberta on March 4, 2019.

We are currently in the midst of what some are calling a “true crime boom,” thanks to a resurgence in great true-crime writing and longform journalism, and the popularity of true-crime podcasts like Serial, S-Town and In the Dark, and documentaries like Making a Murderer and The Jinx. In recent days there’s been a lot of talk about the Michael Jackson documentary Leaving Neverland, and I think we’re going to be hearing a lot more about it in the days to come.

But the popularity of these productions and others are raising questions: What does it mean to really enjoy a true-crime show on Netflix? To be hooked on a true-crime podcast? To really appreciate the way a true-crime story is told? Are we hurting families just by consuming these stories? Are we using the pain of others for our own entertainment?

While true crime might certainly be enjoying a bit of a moment, this is not the first time people have been engaged by true stories of crime and misery, and I think it’s helpful to think about this, particularly in recognizing that a resurgence in this genre is not a sign of some new societal breakdown and decay. In fact, true crime has been around about as long as humans have.

There are cave paintings dating back more than 30,000 years that show people pierced with arrows. These paintings are notable not only because they show that the violence occurred, but also that even our most ancient ancestors had a desire to record it.

Zooming ahead a few dozen thousand years, we come to the popular crime sheets of 18th and 19th century England, which were illustrated and descriptive depictions of crime and criminals, usually sold to spectators alongside the public executions of their subjects.

If you start to think binge-watching a murder documentary on Netflix seems grim, remember that we actually used to go watch executions, and then buy illustrated souvenirs.

As literacy rates increased and newspapers made information more broadly accessible in the early 20th century, crime stories proved to be a constant source of public fascination.

During some trials, newspapers put out extra editions all day, updating readers on every development in the case, and people at times literally fought for copies fresh off the presses. I’ve read reports of people jammed onto courthouse windowsills as they watched the proceedings, the original form of binge-watching.

One such case was the hugely sensational Snyder-Gray trial in 1927, in which a woman and her lover were tried for the murder of her husband. It had everything. A scandalous affair, a seductress, a hapless husband, and the dangerous temptations of jazz. People couldn’t get enough. I mention that case in particular because it went on to inspire countless films and other cultural creations. Writer James M. Cain was among those who watched the trial, and it was the inspiration for his book and then the film, Double Indemnity, which played a role in the development of the whole film noir genre, but I digress.

Florabel Muir, one of the few female crime reporters working in the late 1920s, compared getting through the courthouse during the Snyder-Gray trial as being “like pushing one’s way through a stampede of Texas longhorns,” with hundreds of people shoving their way toward the third floor courtroom to get a firsthand glimpse of the murderous lovers. Ms. Muir described the stairwell and halls of the courthouse littered with hats, eyeglasses, fur collars and shoes, and even girdles that had somehow been torn off their wearers in the crush.

Covering the case as a correspondent for the Universal Service, reporter Damon Runyon noticed with some concern that women seemed particularly interested in the more gruesome evidence.

He described seeing a group of women pushing and shoving to get a closer look at the victim’s blood-stained pillow, which sat on the district attorney’s table as a piece of evidence.

“That scene in the court was one that should give the philosophers and psychologists pause,” he later wrote. “The women were far more interested in the bloody pillow than they would have been in a baby buggy or a dishpan full of dirty dishes.”

And while I think Mr. Runyon may have been overestimating the intrigue of a dishpan full of dirty dishes, he was noticing and wondering about some of the very same things we’re thinking about today. Interestingly, some of the recent stories I’ve seen about the so-called true-crime boom also question why the genre seems to hold particular appeal to women.

I also note that Mr. Runyon, who referred to Ruth Snyder in one story as “a black-garbed, white-faced, tawny-haired leopardess of a woman,” was obviously a bit taken with the case himself. I don’t recall reading any big Runyon features about dirty dishes.

The popularity of true crime grew further with the development of crime comics like Crime Does Not Pay, Famous Crimes and True Crime, which depicted true stories of criminals and their crimes in the popular and engaging new comic-book format. There was so much interest in crime comics — and that interest was seen as so dangerous — that by the late-1940s there was a major movement opposing them.

In some cases the comics were burned in pyres. In 1948, John Mason Brown, a writer and theatre critic at The Saturday Review of Literature, described crime comics as “the marijuana of the nursery; the bane of the bassinet; the horror of the house; the curse of the kids, and a threat to the future.”

There were similar concerns in Canada as well. British Columbia MP Davie Fulton led a successful campaign to make crime comics illegal in Canada and they were outlawed in 1949. The law remained in effect until December of last year.

In the 1960s and 70s, seminal true crime books like Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, Joseph Wambaugh’s The Onion Field, and Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song topped bestseller lists and raised similar tensions.

How are we supposed to feel about a beautiful piece of writing about a real and ugly act? Is it wrong to enjoy it?

I mention all of this to say that it is not a new thing that we are drawn to true crime stories. It is also not new that we are simultaneously disturbed and unsettled by our own interest in them.

I’ve been covering crime stories in-depth for about the past 16 years, as the court reporter at the Regina Leader-Post, then moving on to a position as crime bureau chief at the Edmonton Journal and now, as a feature writer with The Globe and Mail.

In that time, I’ve thought a lot about media coverage of crime and “the misery beat” as it was sometimes called.

I’ve found some people think crime stories are by their very nature morbid and unseemly, and assume others only want to read them because of some kind of prurient fascination or bloodlust, the same way people may watch horror movies.

Think of the time-honoured newspaper adage: “If it bleeds, it leads.” That cliché has always bothered me, as I believe it reflects a serious misunderstanding of why people are drawn to true crime stories. That saying implies people only read a story that “bleeds” because of an enjoyment of other people’s pain. In this way of thinking, a crime story gets attention from the press and public not because it’s important, or profound, or relevant to society and the lives of others, but simply because it’s gory. And if you thought that, I can see why you would hold crime reporting and true crime in low regard.

But after 20 years as a reporter, I can tell you with certainty that is not the case. I know this because I talk to cab drivers and dentists and people at grocery stores and cocktail parties about the stories I’ve covered. I get phone calls and letters and tweets and Facebook messages from the readers of these stories.

Sometimes people tell me a story moved them so deeply it made them cry. Sometimes they say a story changed them. Sometimes they ask how they can help the victims. Sometimes a story spurs people into action — sparking a desire to change law, or raise awareness, or do whatever they can in hopes that whatever happened to the people in that story will never happen again.

These aren’t the reactions of people simply revelling in the gory details of someone else’s misfortune.

Instead, I think people are interested in true crime stories for maybe the most shocking reason of all: Because we care.

And because the stories matter.

Human beings want to know about other human beings. We want to know about what other people do, how they live and what happens to them. This is a deeply rooted part of our nature, a truly fundamental aspect of how we operate in the world. And in many cases, we learn these things through stories. This desire to watch and learn about each other is why there are books and TV shows and movies at all. Why we read comics and magazines and newspapers, why we look at pictures on Instagram, why we follow threads on Twitter and read Facebook posts.

In fact, stories are so powerful that we may read or watch or hear a story about someone we’ve never met, someone from a different time, from around the world, someone who has nothing to do with us, and yet that story can stick with us for the rest of our lives. That is the case with all stories, but it is particularly so with stories that are true.

And we want to share stories about ourselves, too. This is why we tell our families and friends and co-workers something funny or difficult or strange that happened on the weekend. Why we, too, tell anecdotes and write Twitter threads and Facebook posts. Why, when something happens to us, whether good or bad, our first instinct is often to tell someone. When we cannot tell an important story, being unable to share it can, in fact, become a burden.

We are all sharing stories about what it means to be human, from those cave paintings right on down to now.

And crime stories are a big part of that.

That’s because crime stories are about some of the most extreme and profound aspects of human experience. They are stories about what it means to kill another person. About what it means for someone to be killed. About what it means to lose everything. About what it means to survive such loss. About what can come out of such ugliness, and the things that happen after. About whether there can be justice or redemption. Stories, quite literally, of life and death. Good and bad and everything in between. I think this is why we are drawn to them. Maybe we are even programmed to be particularly interested in these kinds of stories, because they can help us make sense of the world and its dangers, and serve as both lessons and warnings.

When a crime or tragedy happens, we want to know what happened, why it happened, whether it could have been prevented, and what its effects are. It is also, sometimes, a time for us reflect on what it would have been like if that horrible thing had happened to us, or to our families, or how we could avoid it and keep ourselves and our own families from a similar fate.

In some cases, and I think of the Humboldt bus crash here, it can even be a time to wonder what it would be like if we ourselves were to be responsible for such a horrible thing.

And while individual stories matter, broader social issues such as domestic violence, mental health, drug addiction, racism, sexual violence, and poverty are also often deeply woven into criminal acts. We can look at and understand huge and vitally important issues in new ways, in part, through recording and reporting on individual cases. Through the real stories of real people.

Crime stories are also about accountability, to question the systems and people that govern us. There is an old adage that justice is not done unless it can be seen to be done, and the media has a significant role in that. We are the eyes of the public.

Done properly, crime reporting can be profound and powerful. It can be a way to give a voice to the voiceless, or to help someone find their voice. It can do what all good journalism should: Tell interesting, important stories that matter. What many have actually said is journalism’s duty, “to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.”

The true cost of crime and violence cannot be fully understood without knowing about the lives it touches.

Crime reporting is not always easy, and it is not always comfortable. But that is the nature of tragedy.

Last week, I happened to catch director Joe Berlinger being interviewed about his new documentary Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, and the true crime genre more broadly, and the idea of making entertainment out of other people’s tragedies.

Mr. Berlinger has been making true crime documentaries for close to 30 years. His 1996 documentary Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills remains, to me, one of the best true crime documentaries ever made. I saw it in the theatre before I ever thought of becoming a reporter, and it is the first true crime work I remember. The first time I really noticed how beautiful and moving and important a story about something so terrible could be.

Though Mr. Berlinger has previously said he set out to make a movie about a group of teens who committed horrible, senseless murders, his research instead exposed the wrongful conviction of three young men, one of whom had been sentenced to death for a horrific crime, and the documentary ultimately played a huge role in them gaining their freedom.

Damien Echols has said he believes he would have been executed were it not for Mr. Berlinger’s documentary about the case. These stories matter.

In the interview, Mr. Berlinger said, “That phrase ‘true crime’ somehow conjures up an image of wallowing in other people’s misery for the sake of the entertainment of others, and I’m very sensitive to that criticism. There are certainly works in this category that fulfill that. My answer to how to honour the victims is to tell a responsible story.”

As Mr. Berlinger notes, not all true crime is created equal. I’m sure we could all bring to mind a dime-store paperback with a cover drenched in inked blood spatters and some salacious title. I particularly remember those books from the 1980s.

But a new interest in true crime stories is a chance to do better. To show the power of these stories and this genre, and even to move past the stigma of it.

From the left: A broadside detailing a murder near Leatherhead in Surrey, 1826; arrest of the anarchist Ravachol 1892, Le Petit Journal; crowds wait outside Don Jail while the last two hangings, of Ronald Turpin and Arthur Lucas, take place in Canada on Dec. 11, 1962.

As our culture changes, so does our work evolve.

As journalists and documentarians of true crime, we have to constantly consider why we do what we do, and how we do it. We need to be thoughtful, to evaluate and re-evaluate the choices we are making, to consider our intention in what and how we present something, to be able to explain and stand by the work we do.

As consumers of true crime, our obligations aren’t actually much different. We can speak with our time and our attention to the work we believe in; work that questions, that elevates, that teaches, that amplifies, that gives voice. Those choices support the creation of more good and ethical work.

Instead of abandoning true-crime stories, or fighting our own interest in them, we should be holding them to the highest standards, ensuring that reporting of true crime is responsible and accurate and thoughtful and fair.

And, most importantly, we all need to remember that these are real stories about real people.

They are true crimes.

And that is exactly why they matter.

Jana G. Pruden

Jana G. Pruden