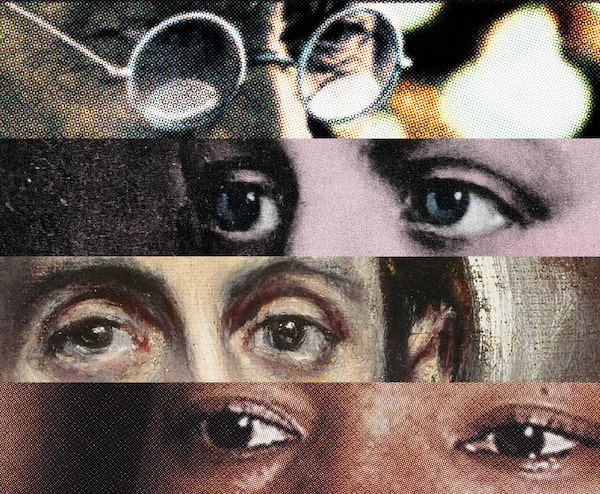

History is full of inspiring charismatic figures – Mahatma Gandhi, Jeanne d’Arc, Jesus Christ, Martin Luther King Jr., but meaningful social change comes about through the work of many people. Photo Illustration: The Globe and Mail. Source images: AP Photo. Painting detail: Salvator Mundi, El Greco.

Barry Lopez is the author of several books of fiction and non-fiction, including Arctic Dreams, which won the National Book Award. His latest book is Horizon, from which this essay is adapted.

World history is full of inspiring charismatic figures – Muhammad, the dissenter Jesus Christ, Jeanne d’Arc, Mahatma Gandhi, Albert Schweitzer, Dorothy Day, Jose Marti, Martin Luther King Jr., Wangari Maathai – but historians of social change often point out that meaningful social change, the kind of change that improves the conditions in which people live, comes about through the work of many people. A charismatic figure might galvanize change and stand as its historical representative, but human beings are social animals. They take care of one another through continuous social interaction. The popular notion that in bad times, heroes show up is an enduring literary device, but it is wiser for a population in difficult straits to effect a means of courteous and respectful social exchange – conversation and ceremony – than to wait for a hero to speak. I emphasize this because I’ve so often been struck by the difference between a society that believes wisdom is part of the fabric of a community, and that it is best represented in the words and actions of particular people (elders), and a society that believes wisdom is only to be found in certain people. The difference for a community would be the difference between choosing to act heroically as a group or waiting for a hero to act.

The human effort to listen to each other is, for me, one of the most remarkable of all human capacities, although hardly a word is ever said about the human capacity to listen to another person. I bring this up because if the creation and maintenance of effective social networks, a particularly striking human attribute, is necessary to protect individuals against threats to this species’ health, then the ability to listen carefully to one another becomes critical.

A key to maintaining large, effective social networks is having the ability to comprehend what someone else is thinking and, importantly, being able to understand that whatever someone else is thinking, it might be different from what you yourself are thinking in the same situation. It’s not until a child is 4 or so that she or he can grasp that someone else who sees the same world they do sees it differently.

The ability to understand how others perceive a situation amounts to a kind of empathy. It can lead to an amelioration of tensions in a group faced with a problem. Or, of course, it can lead to the manipulation of others in the group.

What most of us notice in small social settings, I think, is not the ability of another person truly to empathize with someone else’s point of view, but the inability of some people to do this. They cannot entertain another point of view without fearing the loss of their own, or they’re simply less capable of being empathetic. Autistics and psychopaths, although some in either group might be highly intelligent, have a limited ability to empathize, to be attentive to the needs, the fears and the hopes of other people. They quickly become impatient with a world not organized according to their preferences.

The relevance of these thoughts about empathy and social co-operation lies with the convergence in our time of two extremely powerful forces. One is ecological – our ability essentially to bypass nearly every natural control on the increasing size of our population. Only a catastrophic viral outbreak or widespread nuclear warfare now threatens man’s ability to exploit all of Earth’s ecosystems in order to secure energy, sustenance and economic profit.

The second powerful force is the accelerating rates of change in the man-made world, when considered in the light of recent research on the biochemical, morphological and histological landscape of the human brain. The social and cultural development of H. sapiens over the past 55,000 years has been relatively swift. The rate of change in the man-made environment today is so great, in contrast, that the idea that one generation is meant to teach the next generation how to manage has begun to seem quaint. Also, evolutionary psychologists question whether all human beings have the same ability to adapt to such rapid change. Some people, then, might seem marked for marginalization if human societies are to continue to pursue higher levels of efficiency or adapt easily to increasing amounts of social control. We’re reluctant to address publicly the inability of certain people to “keep up” for fear of being regarded as bigoted, intolerant, chauvinistic or xenophobic. The failure to speak in defence of marginalized or persecuted groups is a constant in recent human history. It is also an act of cowardice that asks to be reckoned with before mankind faces truly staggering shortages of energy, freshwater and food.

If H. sapiens’s future is threatened by environmental factors, both natural and anthropogenic, and if the ability of many people to cope with the complexity of the man-made environment is compromised, and if the need for co-operation seems great, how are we to tone down the voices of nationalism, or of those in support of profiteering, or religious fanaticism, racial superiority or cultural exceptionalism? If economic viability trumps human health in systems of governance, and if personal rights trump community obligations at almost every turn, what sort of future can we expect never to see?

All people, every culture, every country, now face the same problematic future. To reconsider human destiny – and in so doing, to leave behind adolescent dreams of material wealth, and the quest for greater economic or military power, which already guide too much national policy – requires reassessing the biological reality that constrains H. sapiens. It requires “resituating man in an ecological reality.” It requires addressing the inutility – the biological cost to the ecosystems that sustain him – of much of mankind’s vaunted technology. Whether the world we’ve made is not a good one for our progeny – asking ourselves about the specific identity of the horsemen gathering on our horizon and what measures we need to take to protect ourselves – requires a highly unusual kind of discourse, a worldwide conversation in which the voices of government and those with an economic stake in any particular outcome are asked, I think, to listen, not speak. The conversation has to be fearlessly honest, informed, courageous and deferential, one not guided by concepts that now seem both outdated and dangerous – the primacy of the nation-state, for example; the inevitability of large-scale capitalism; the unilateral authority of any religious vision, the urge to collapse all mystery into one meaning, one codification, one destiny.

When I’ve passed through different troubled parts of the world and sought local advice – on Indigenous reservations in the United States, at Banda Aceh in northern Sumatra after the Boxing Day tsunami in 2004, in Western Australia during the heady days of mining ceaselessly for iron ore (financed by the Chinese) – I’ve seen the same pattern of coping with disaster. Deferential local co-operation. This suggests to me that for many people in difficult circumstances, the notion of needing help from a centralized authority, especially one living at a remove from the problem, and the notion of fully protecting certain types of economic progress are not much on people’s minds.

What I see consistently in these situations is the emergence of individuals who embody that culture’s sense of competence into positions of authority. They are its wellspring of calmness. They do not disappear with defeat or after setbacks. They do not require reassurance in their commitments to such abstractions as justice and reverence. In traditional villages, they’re called the elders, the people who carry the knowledge of what works, who have the ability to organize chaos into meaning and who can point recovery in a good direction. Some anthropologists believe that the presence of elders is as important as any technological advancement or material advantage in ensuring that human life continues.

I’ve not travelled enough, read enough, spoken to enough people to know, but this observation feels almost eerily correct to me. At the heart of the generalized complaint in every advanced or overdeveloped country about the tenor of modern life is the idea that those in political and economic control are self-serving and insincere in their promise to be just and respectful. I sat down once at my desk and wrote out the qualities I observed in elders I’d met in different cultures, nearly all of them unknown to one another. Elders take life more seriously. Their feelings toward all life around them are more tender, their capacity for empathy greater. They’re more accessible than other adults, able to engage in a conversation with a child that does not patronize or infantilize the child, but instead confirms the child in his or her sense of wonder. Finally, the elder is willing to disappear into the fabric of ordinary life. Elders are looking neither for an audience nor for confirmation. They know who they are, and the people around them know who they are. They do not need to tell you who they are.

To this list I would add one more thing. Elders are more often listeners than speakers. And when they speak, they can talk for a long while without using the word “I.”

Living in one of the most highly advanced of human cultures, I often wonder, What have modern cultures done with these people? In our search for heroes to admire, did we just run them over? Were we suspicious about the humility, the absence of self-promotion, the lack of impressive material wealth and other signs of conventional success? Or were we afraid they would tell us a story we didn’t want to hear? That they would suggest things we didn’t want to do?