If architect Rohan Walters wasn't so soft-spoken, his fist would surely be pounding the table to help underline his frustration.

"For every building we put up, we have to get water to it, and get the sewage from it," he says, his voice raising only a little. "It's massive.

"Do you know how many smart people we have in this city?" asks the 56-year-old, rhetorically. "It's ridiculous: Enough, let's do it!"

I can't claim to know as much about sewage and water treatment as Mr. Walters does – along with trying to solve the emerging problems of 21st-century urban centres, most know him as designer of the "Lego House" at 157 Coxwell Ave. and his own "Triangle House" at 1292 College St – but I've come to his dining table to absorb as much as possible.

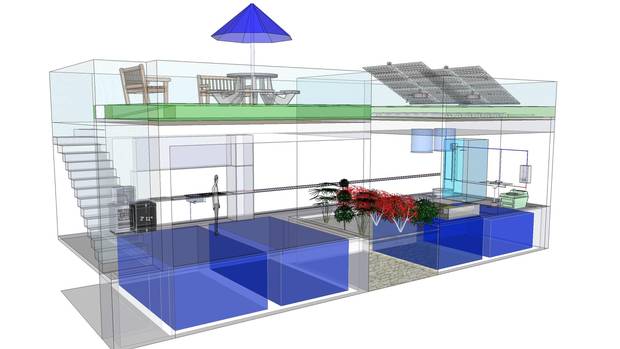

Seated next to us is Princeton-educated engineer Andrew Hellebust, 50, whose voice is only slightly louder. "A house like this could, maybe, reduce its peak demand on the city by 90 per cent or something," he says, motioning to the graphic on the glowing laptop screen in front of us. "So that little house could be attached to an umbilical cord to the city's infrastructure rather than a big pipe."

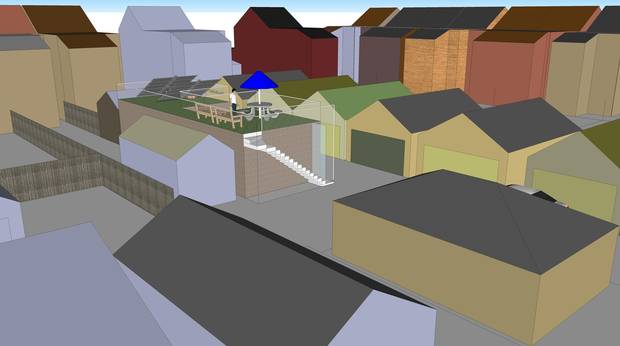

The "little house" on the screen has yet to be built. In fact, "Water House," as this forward-thinking pair has dubbed it, was designed for a client back in 2010 as a laneway dwelling, but a series of events and a subsequent sale of the four-garage-wide property put the kibosh on the project. But the idea is so good, so vital, Mr. Walters has not given up; a recent passionate blog post about it at spacesbyrohan.com intrigued this writer enough to arrange a meeting.

The house was originally designed for a client in 2010 as a laneway dwelling.

The Water House does two big things. First, as originally designed, it doesn't connect to the city's water system at all. Instead, by using a series of large cisterns, storage tanks, and cutting-edge technology, it collects rainwater and transforms it into shower- and sink- grey water, it stores and breaks down human waste (via an electrical composting toilet), and it creates its own drinking water via an atmospheric water generator. To further close the loop, some of the grey water travels up to the green roof to feed the plants. Fertilizer manufactured on site (from guess what) could also be used to feed the roof.

The second thing it does is to supply itself with its own power via solar panels.

To ensure this bold and complex idea would get the city's green light (whether they could build in their client's laneway was a separate matter), the duo sat down with a half-dozen City of Toronto specialists. "And they were quite supportive," says Mr. Walters, his voice now back to its usual timbre. "They gave us a heads-up on a couple of things we're going to have to address with them …"

Walters is still passionate about the project, which uses a closed-loop system to manage waste water.

"… The City is probably unfamiliar with looking at waste-water when it's not in a sewer," Mr. Hellebust interjects. "One of the ideas is that you would have a small amount of excess waste water effluent, and could you, in theory, infiltrate that into the soil below a house?" Of course, since the current building code wouldn't permit this, he adds, more work still needs to be done.

While it may not be sexy, the pair is concerned that the gallons and gallons of clean water used "as a means of moving our fecal material off to a distant sewage treatment plant" is no longer sustainable, especially when one considers that the GTA welcomes hundreds of thousands of new residents each year.

"I'm trying to think ahead 50 years," Mr. Hellebust says. "We just have to capture this stuff and put it back onto farmland … a good option to consider is toilets as receptacles that are part of a bigger system; you could export this through the brown bin … like the green bin – you could have a vacuum system to move this stuff around, you could have the reverse of an oil pipe in a house, the truck comes up and pulls it out."

Walters says Water House would be linked to the city’s infrastructure via an ‘umbilical cord’ instead of a ‘big pipe.’

If this dynamic duo seems obsessed with doo-doo, perhaps it's because they also worked on a proposal for a small washroom building at Dufferin Grove Park in 2010. Although the park has existing washrooms, the playground area to the south does not, and Mr. Walters and Mr. Hellebust (along with other experts), proposed a Canadian-made, Phoenix composting toilet to avoid paying a minimum of $73,000 to bring sewer lines to the site (not to mention the cost of transporting water to and from thereafter) in a comprehensive, 52-page feasibility study. As with Water House, it has not been built either.

Mr. Walters, his voice rising again, says he can't understand why these "really tremendously supportable and good ideas that are safe, that are clean, that will help housing, that will help the water situation, that will provide interesting opportunities for architecture," fail to ignite the city's – or even the public's – imaginations.

Maybe, this writer suggests, it'll take sexy to sell Water House; after all, the electric car wasn't cool until Elon Musk's Tesla came along.

"That's what designers are for!" Mr. Walter says, punctuating his point with a clap.

Touché, Mr. Walters, touché.

Want to interact with other informed Canadians and Globe journalists? Join our exclusive Globe and Mail subscribers Facebook group