A half-century ago, condominiums were an obscure, novel concept in home ownership. Made legally possible in 1967, the notion of owning a suite, and then paying fees to maintain common areas, was seized on by governments as a solution to a crisis in affordable housing in the late 1960s.

It did not work. But 50 years later, while it remains for many the only hope of affordable home ownership in Toronto's red-hot housing market, the tower-of-glass luxury condo has also become a dwelling of choice for a new more urban generation, radically remaking entire Toronto neighbourhoods in the process.

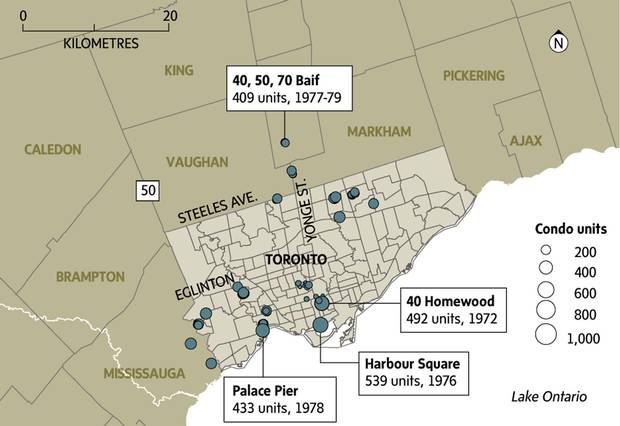

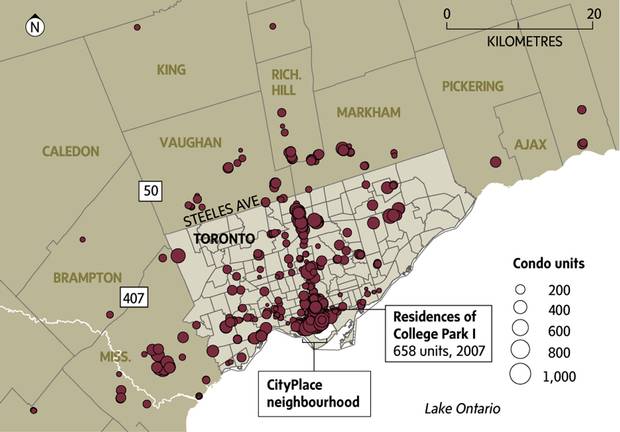

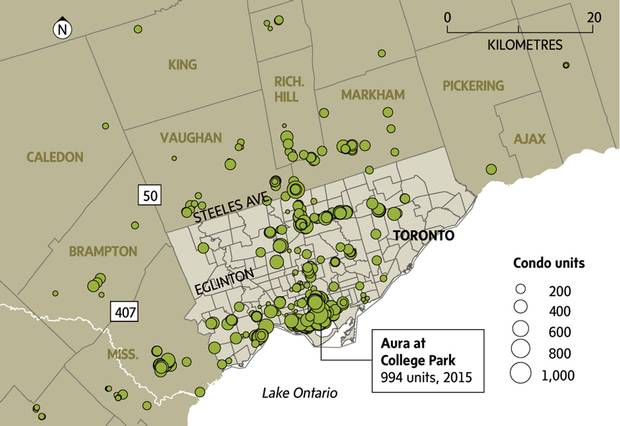

Note: The following maps indicate completed condo buildings by number of units in the Greater Toronto Area, through September, 2016. Some buildings lay outside the map boundaries. (Source: Urbanation)

1970s

11,697 units added

House prices were rising steadily in the late sixties, prompting very familiar anxieties about young couples unable to afford homes. Condos – in high-rises but also townhouse complexes in the suburbs and downtown – were among a slate of solutions embraced by governments, who also handed out millions of dollars in subsidies to builders. Some optimistically predicted condo growth would outpace single-family homes, with marketing aimed at young couples and "empty nesters."

By the early 1970s, complaints over shoddy construction and a glut of units started to emerge. Condos soon won a reputation as drab and unappealing. Sales collapsed mid-decade, prompting promoters to try out new gimmicks: One promised to pay any hikes to hydro, heating and property taxes until 1980.

In 1973, the city became embroiled in a battle over blockbusting and high-rise development, prompting mayor David Crombie and reformers on council to bring in a two-year moratorium on new buildings more than 45 feet in the downtown core.

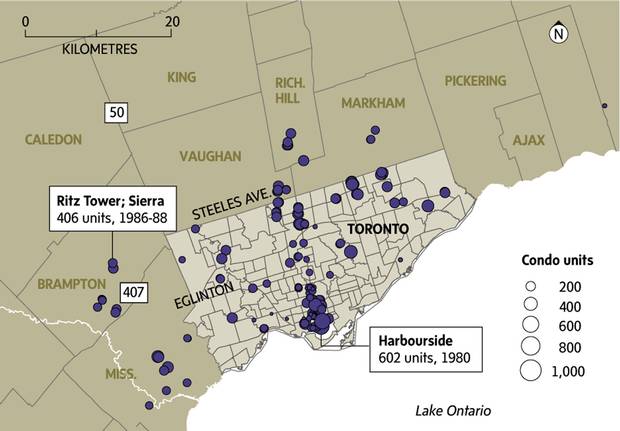

1980s

30,881 units added

Boom times soon returned, as the decade most associated with yuppie excess brought with it a wave of new luxury condos in Toronto, as it did in many other cities around the world.

"Vacant lots all over downtown Toronto are sprouting condominiums of late," The Globe reported in January, 1981. "No sooner has one of the glamorous edifices begun to climb the Toronto skyline than the sold out sign is posted, and the next development announced."

The flagships of this new breed were the Palace Pier and Harbour Square developments on the city's waterfront, completed in the late 1970s. Others, including Olympia & York's Queen's Quay, completed in 1983, would follow. But as many as half of the city's high-end units, The Globe said, were snapped up by businesses or investors.

Controversies erupted mid-decade over flipping and sweetheart deals for insiders at Harbourfront, where towers were built much taller than promised in defiance of objections at city hall. After a dip in 1987, the real end to the party came in 1989, as the city's real estate bubble finally burst.

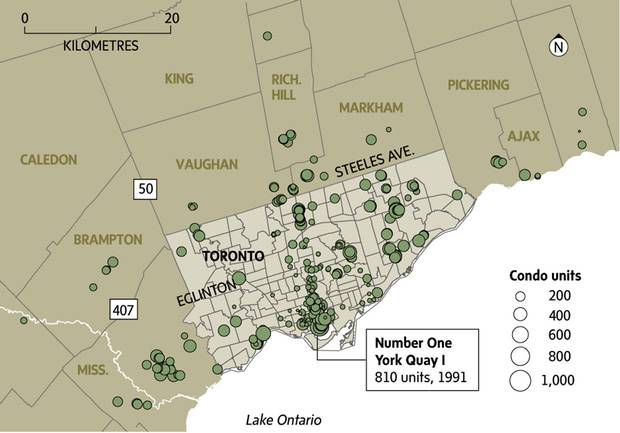

1990s

49,503 units added

The decade began with the market in a hole that just kept getting deeper, as a broader recession rocked the country. Toronto was drowning in unsold condos, and nobody was buying.

Prices sank more than 30 per cent. In April, 1991, The Globe reported that Toronto had 20,000 empty condo units. Increasingly, they were being rented out, rather than lived in by owners.

But by late 1997, new condo starts were shooting back up to 1989 levels. And they were creeping into new parts of the city, where converted factories were marketed as lofts and even newly built condos were made to mimic lofts. Demographic shifts, including downsizing boomers and young couples embracing an urban lifestyle and eschewing lengthening daily commutes by car, were increasingly driving demand.

As the decade neared its close, a 45-storey luxury hotel-condo complex next to Toronto's historic Pantages Theatre – home then to Phantom of the Opera and known at the Ed Mirvish Threatre – sold out in just a few days.

2000s

103,683 units added

Toronto's condo euphoria would see twice as many units completed in this decade compared with the 1990s. Construction started on several new hotel-condo projects that threatened to flood the city with five-star luxury, including the Ritz-Carlton, Shangri-La, the new Four Seasons in Yorkville and Trump Tower, which would later become mired in lawsuits and financial problems.

At the decade's beginning, sales of condos were smashing 1980s records, even amid concerns of a glut. CityPlace, the city's largest residential development, on railway lands to the west of downtown, began a dozen years of construction. The frenzy was interrupted only briefly by the global financial crisis, triggered by the U.S. housing crash in 2008.

Its most prominent Toronto casualty would be Kazakhstan-based Bazis International's proposed condo tower at 1 Bloor East, which was backed by ill-fated U.S. investment bank Lehman Bros. Great Gulf Homes would eventually pick up the marquee site.

2010s

109,497 units added

By 2010, the financial crisis was already forgotten, and real estate markets were hot. Critics urged city planners to force developers to move away from shoebox-sized bachelors for young singles and create larger units to accommodate families with kids. With condo prices up 10 per cent year over year in April of 2010, the CEO of Royal LePage warned of "irrationality" in the market.

Sales in Toronto would cool that summer, for the first time since 1994. But this was a blip. Developers kept unveiling plans for gleaming towers on underused sites.

Thousands of new condo-dwellers were living in downtown neighhourhoods, increasingly walking or cycling to nearby jobs. Condo sales outside central Toronto, in the so-called 905 suburbs, were also smashing records.

Government tinkering with mortgage rules did not stop the boom. In April, 2017, Ontario announced a suite of measures, including a tax on "non-resident" buyers similar to one imposed in B.C., to cool the market.

BUILDING TORONTO: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Done Deals: See inside a midtown Toronto condo that sold in under three days