Paul Robinson was visiting Singapore for business in mid-January and decided to drop by a sales and marketing "road show" for the opulent new condo tower, the Butterfly, to be built in downtown Vancouver.

The Butterfly is one of the last designs by Vancouver's legendary architect Bing Thom, who died last year. When the 57-storey skyscraper is completed by 2022, it will be one of Vancouver's iconic structures, centrally located at 969 Burrard St., with the city's best views. It will also be one of the city's most expensive. To live in one of the units on the upper floors of the beautiful building will cost a buyer millions of dollars.

Mr. Robinson, a 36-year-old engineer from Ohio, has been renting an apartment in the West End for eight years with his fiancée. He can't afford to buy in Vancouver and even if he could, he doesn't trust the market. He wanted to see first-hand what it's like to be a foreign buyer purchasing a Vancouver condo. He had to be in Singapore anyway, so he set up an appointment and went to the sales presentation at the Four Seasons Hotel there, which was entirely devoted to sales of the Butterfly.

In the hallway, Mr. Robinson saw a poster advertising Vancouver as having "a low vacancy of 0.9 per cent" and "capital appreciation of 13.5 per cent," selling points for investors. Another poster titled Why Vancouver cited the city as one of the top five most livable cities in the world, because of quality of life, infrastructure and livability. It cited a strong economy, migration, "supply of homes below required inventory" and "rapid increase in home prices."

He also spotted a poster for Westbank Corp.'s Vancouver House, another striking condo building under construction down the street from his apartment in Vancouver.

"I'm sure it's going to be a really nice building. I wouldn't mind living there," he says. "But what's hilarious is, I'm seeing it on a poster in Singapore."

Mr. Robinson told the salespeople he was an American who wanted to invest in a condo in Vancouver. He was told that there were one-, two- and three-bedroom apartments available at the Butterfly, as well as subpenthouse and penthouse units, starting at $1.22-million.

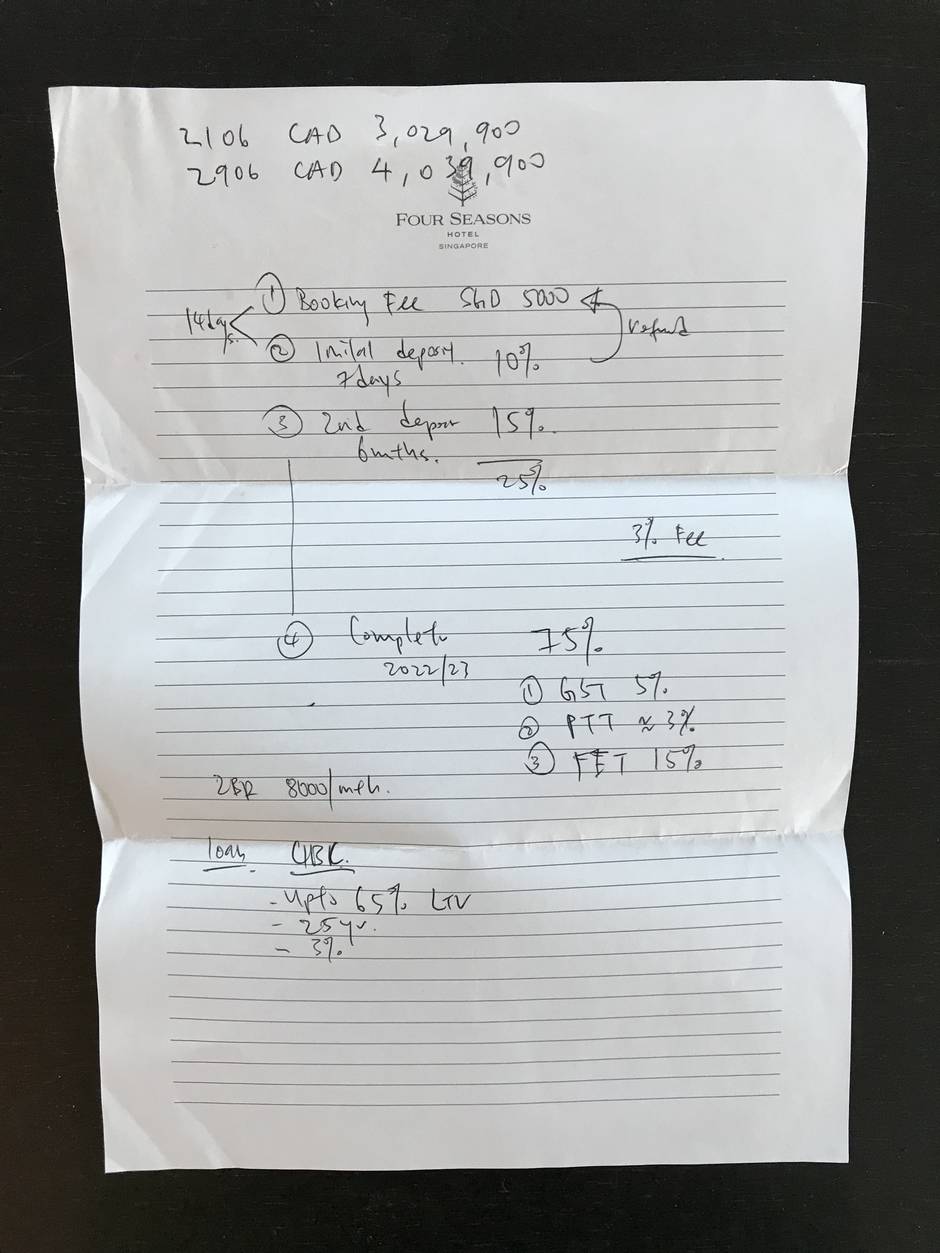

Mr. Robinson spent about an hour talking to a salesperson and watching other interested investors stream in. While there, he began to see the appeal of Vancouver through their eyes. Mr. Robinson was shown the floor plan for a two-bedroom unit on the 21st floor of the Butterfly for $3,029,900. He also looked at a unit on the 29th floor for $4,039,900. He was told the building would include an Olympic-size swimming pool and fleet of BMWs for resident use. He showed me a work sheet that broke down the fees, including a refundable "booking fee" of $5,000, a 10-per-cent deposit due within seven days and a second deposit of 15 per cent within six months.

"These are just folks looking at investment property," he says. "It's similar to [Canadians] buying a timeshare in Florida – there's nothing inherently wrong with any of this," he says. "Everything there was above board. I could totally understand why everybody would want to buy property in Vancouver. It's not weird to me at all."

However, Mr. Robinson says he was encouraged by the salesman – who worked for a global real estate marketing company – to purchase a unit as a speculative investment, flipping the property before the building completes, thereby dodging some taxes - 5 per cent for GST, a 3-per-cent property-transfer tax and the 15-per-cent foreign-buyers tax - which only kick in at completion. (He was told Westbank takes a 3-per-cent fee when presale owners assign contracts. Charging a fee for assignments is a fairly standard practice in the development community. Westbank confirmed the fee.) The work sheet shows that if he did take possession of the unit, he'd owe the 5 per cent for GST, a 3-per-cent property-transfer tax and the 15-per-cent foreign-buyers tax. CIBC offered loans of up to 65 per cent of the value. He was told he could rent the unit for about $8,000 a month.

"The guy definitely stated that the purpose of the investment, as he saw it, was capital appreciation and not to hold onto it and rent it out. Clearly, that is the way it was being pitched," Mr. Robinson says. "Although he talked a lot about how nice the building is going to be, he wasn't even pitching it as a pied-à-terre – although maybe he would pitch that angle more to wealthy jetsetters."

He takes issue with speculative purchases that he sees as driving up prices for permanent residents such as himself and other working locals who want to live and work within the Vancouver region, put down roots and raise families. The West End has long been a highly livable neighbourhood – dense, with the city's largest stock of rental. The area is transforming owing to skyrocketing real estate prices.

Mr. Robinson doesn't blame developers, but he blames government policies that have allowed speculation to run rampant.

"I really take offence to the fact that I have to learn about global flows of capital and I have to read Wall Street Journal articles just to find out if I can afford a home in my own town. It should be a reasonable expectation that if you want a home, you can go buy one and you should be competing with other people who live in that city and who pay taxes there and have a job there."

A poster from developer Westbank at a Singapore sales presentation.

Paul Robinson

Local marketing for the project began in November, as part of developer Westbank's Local First program. Last fall, the City of Vancouver approved a new policy that locals should get the first 30 days of a presales marketing campaign to buy into a property. Developers can voluntarily include the condition when they apply for a rezoning. A few developers have responded by making it part of their own marketing policy.

Local residents, as defined by the city policy, "are residents who live or work in Metro Vancouver." However, the definition can vary from project to project, as long as it meets the intent, according to the city.

Westbank publicist Jill Killeen says the company voluntarily created its own Local First program when it officially launched presales of the Butterfly in Vancouver on Dec. 14. According to Ms. Killeen, 90 per cent of the units in the Butterfly sold to locals within the first 30 days of sales. Ms. Killeen said of the 331 homes, only 30 units remain for sale. They extended availability to international buyers in mid-January at sales centres in Singapore and Hong Kong.

"We anticipate the majority of those 30 remaining homes to be sold locally," she wrote in an e-mail.

As well, she dismissed recent media reports about purchases by "shell companies."

"The vast majority of buyers purchase in their real names," she said. "If a buyer does purchase in the name of a corporation then Westbank verifies they are dealing with the director of that corporation."

Sales of the Butterfly are just one example of Vancouver's globalized housing market. Many Vancouver developers – and developers in other gateway cities – are selling units overseas, including units in projects that are mid-market in their pricing. Sales and marketing company SQFT Global Properties, specialists in overseas property marketing in the Asia-Pacific, shows nine Vancouver projects on its website. Onni Group's the Mark is one of them, with prices starting at $299,900. The remaining eight are Westbank projects that are mid-range to expensive on the price spectrum, including Horseshoe Bay, Joyce, Alberni by Kengo Kuma, 188 Keefer, Vancouver House, Kensington Gardens and Granville at 70th.

Ms. Killeen says the company did not sell any units in Westbank's Granville at 70th, 188 Keefer, Horseshoe Bay or Joyce projects. "Westbank did not know those projects were on the SQFT website and has requested them to be removed," she said in an e-mail.

Hong Kong company Savills advertises 2 River Green in Richmond, by Aspac Developments, as well as Concord Pacific's Concord Brentwood in Burnaby on its website, directing buyers to a Hong Kong-based realtor.

Dallas Rogers, urban studies professor at the University of Sydney in Australia, wrote The Geopolitics of Real Estate and studies housing poverty in relationship to global wealth. He is familiar with the weekend condo presentations held at five-star hotels in Singapore. Singaporeans, as with the Chinese, have an appetite for presales in Australia, he says. According to a recent report by Hong Kong-based international real estate marketers Juwai.com, 19 per cent of Chinese buyers surveyed had plans to purchase property in Australia this year. Twenty six per cent were going to look at U.S. properties and 14 per cent of buyers had plans to purchase in Canada. The top Canadian cities for investment are Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Ottawa and Calgary, in that order, Juwai.com chief executive Carrie Law said.

"People approach you with 'off the plan' sales propositions for real estate developments in Vancouver, London and Sydney," Dr. Rogers wrote in an e-mail.

Off-the-plan is better known in Canada as a presale.

"Our Global Real Estate Project research shows that the sales staff in places like Singapore have a very good working knowledge of the taxation, foreign investment, visa, immigration and education rules. The sales staff use this information in their sales pitch to potential foreign buyers; playing off one set of rules against another.

"Much will depend on what the investor is looking for in a foreign property investment. This could range from a potential long-term retirement property, a place for their kids to live in while they study at a foreign university or a place to park their capital for short-term speculation.

"If it is capital for short-term speculation that the investors are looking for, then yes, Vancouver might be more appealing than Sydney when you have the option of shopping around at a real estate fair in Singapore."

Many argue the new city policy to prioritize locals at the start of a presales launch won't return the housing stock to local income-earners because it's a question of money earned elsewhere. The percentage of homes in the new buildings that are purchased with foreign money is, of course, an unknown. But the source of the money is, to Mr. Robinson, the crux of the problem. People working at local jobs can't compete.

"Let's be real, this is what's going on: For the last 30 years properties in Vancouver have been bought up by people who don't earn money in Vancouver and don't pay taxes in Canada – that's how you can have the average home price get to 25 times the average income," Mr. Robinson says.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article included an incorrect description of taxes paid by foreign buyers. In fact the foreign buyers of Vancouver condominiums who purchase a unit as a speculative investment and who reassign the property before the building is complete can avoid paying the 5 per cent GST, 3 per cent property transfer tax and 15 per cent foreign buyer's tax. Capital gains taxes would still be applicable. This version has been corrected.