Canadian auto executive Keith Henry was enjoying a vacation in Florida this week when Donald Trump's Twitter feed caught his immediate attention.

Mr. Henry is president of Windsor Mold Group, a parts maker with three factories in and near Windsor, Ont., five in the United States and one in Queretaro, Mexico. Prior to the U.S. election in November, the executive had been contemplating whether to expand the Mexican operation. Then Mr. Trump won a surprise victory on Nov. 8, partly on a promise to rip up the North American free-trade agreement and make U.S. manufacturing great again.

If anyone doubted the president-elect's resolve to do just that, those doubts are gone now. Before he is even inaugurated, Mr. Trump seems determined to try to rewrite the rules governing the North American automotive business, 140 characters at a time. This week he turned up the heat, using Twitter to threaten to impose border taxes on vehicles General Motors Co. and Toyota Motor Corp. ship to the United States from Mexico.

His tweet warning to GM had barely been digested when Ford Motor Co. cancelled plans to build a new $1.6-billion (U.S.) assembly plant in Mexico, which had drawn fierce criticism from Mr. Trump during the election campaign.

"I was cautious then and I'm even more cautious now" about building a larger business in Mexico, Mr. Henry said in a telephone interview as he was driving back to Windsor. "The events of the past week have given me even more pause to think."

The hectoring of three global giants in the world's largest manufacturing industry by the most powerful politician sent shudders through head offices from Japan to Detroit to Ontario. The threat of tearing up NAFTA or imposing big tariffs on vehicle exports into the United States is a serious one as Mr. Trump seeks to force companies selling in the U.S. market to keep jobs in the country.

Auto makers and parts suppliers in Canada have so far escaped – at least publicly – Mr. Trump's Twitter wrath.

Employees with Ford Edges on the line following Ford’s official kick-off of the new 2015 Ford Edge production at the assembly plant in Oakville, Ontario on Thursday, February 26, 2015.

Peter Power/For The Globe and Mail

But a quarter of a century of continental free trade has transformed the auto industry – so much so that almost all global auto makers from Audi to Toyota have created intricate supply and distribution chains that stretch across the two borders. The end of the trade agreement would disrupt all of that, creating chaos in auto logistics and investment. As Mr. Henry's comments show, the mere threat of it is likely to cause at least a temporary freeze in new investment in some places.

For Canada, the consequences of Mr. Trump's anti-trade crusade are massive. At stake is the country's position as a nation that punches above its weight in the global auto sector. Although there is no home-grown auto maker, car makers as a group build more vehicles in Canada than they sell. That, in turn, has spawned a successful domestic auto parts sector; companies such as Magna International Inc., Martinrea International Inc. and Linamar Corp. are among the handful of large Canadian manufacturers that can be described as global champions.

If Mr. Trump follows through and creates a tariff wall protecting the U.S. industry, several thousand direct jobs at Canadian parts companies are in jeopardy and potentially more than $60-billion (Canadian) worth of finished vehicles that are made in assembly plants in the auto heartland of southern Ontario and delivered to Americans. For Canadian parts makers that now are now lean, efficient and competitive after having survived the original shock of NAFTA, the threat to Mexico is also a menace to them. Any actions that would halt the expansion of vehicle assembly in that country would choke off one of their key growth markets. Mr. Henry said any parts maker would be apprehensive about growing in Mexico until the new administration makes its North American trade strategy clear.

"I would even extend that into Canada," he said. "If you're a U.S. supplier or a European supplier looking to expand into North America, would you consider establishing or increasing your production capacity in Canada?"

The potential ramifications to Windsor Mold aren't confined to its Mexican operations, he said in an interview in the boardroom at the company's Tenneplas plant in Pulaski, Tenn., a few weeks after the election. Tenneplas, which sits about a 90-minute drive south of Nashville in a town that has the dubious distinction of being the original home of the Ku Klux Klan, ships plastic parts to Mexico as well as assembly plants in Mississippi, Michigan, Missouri, Kentucky and Indiana.

As country music plays over the plant's intercom, seven-metre long moulding machines pop out plastic radiator shields, door trim and parts called cowl vents that sit at the base of a vehicle's windshield. The Windsor Mold operation is a prime example of the auto sector in the NAFTA era: A Canadian company that adroitly expanded in the United States and Mexico as the auto assembly industry moved south from the Great Lakes region and is now making parts in all three countries that are snapped into vehicles sold in all three countries.

Mr. Trump may want to turn back the clock to an era when a made-in-America sticker on a car meant precisely that. But at what cost?

Ford and Lincoln vehicles are parked outside the Oakville Assembly Plant in Oakville, Ont., in November, 2016.

CHRIS HELGREN/REUTERS

Canada was originally a reluctant partner in the negotiations for a continental trade agreement. Ottawa's decision to join the talks was in part defensive – to make sure we stayed on the same path as our largest trading partner – but also to correct some of the defects in the 1989 Canada-U.S. free trade deal.

The United States wanted to help bring stability to its troubled southern neighbour and open a new market to U.S. companies. But the NAFTA deal was not without controversy – especially when maverick presidential candidate Ross Perot got some traction with his campaign against it. "If you're paying $12, $13, $14 an hour for factory workers and you can move your factory south of the border, pay a dollar an hour for labour … and you don't care about anything but making money, there will be a giant sucking sound going south," he said in one presidential debate.

"Giant sucking sound" became one of the most memorable phrases of the election. But Bill Clinton won and NAFTA became a reality on Jan. 1, 1994.

In the early years of the deal, investment by auto makers poured into the southern United States, not Mexico. Since 2010, however, vehicle companies have pumped about $21-billion (U.S.) into new and existing factories in Mexico. That's about one-third of the $63-billion global auto makers invested in U.S. facilities. All that investment has shifted the centre of gravity of vehicle manufacturing southward from the days when the Great Lakes basin dominated. The operating system for auto makers and their parts suppliers in Canada, the United States and Mexico is now based on the trade agreement and duty-free access of vehicles and parts among the three countries.

Pedestrians in downtown Oshawa, Ont. pass by murals painted on the walls of the bus station on July 20, 2013.

Peter Power/The Globe and Mail

Vehicles built in any one of the countries are sold in all three. Components manufactured in one of the countries are assembled into vehicles made in that country or one of the other NAFTA nations, sometimes all three. Finished vehicles and the parts that go into them cross borders seamlessly – although the perpetual mess at the Windsor-Detroit border is one nagging reminder that transportation is not as smooth as auto makers and their suppliers would like.

"It's like an ecosystem," said Mr. Henry. "It's very interconnected and it's very related." The creatures in that ecosystem are on high alert given Mr. Trump's hostility toward NAFTA and his threats to impose tariffs of as much as 35 per cent on vehicles made in Mexico.

NAFTA is "one of the worst deals ever made of any kind, signed by anybody," he declared during a September debate with Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton in the presidential campaign. Executives of Canadian auto parts makers beg to differ.

"We've spent a ton of time making the most efficient logistical supply chain in the history of the world," said Rob Wildeboer, executive chairman of Martinrea International Inc., the third-largest Canadian auto parts supplier as measured by annual revenue. "That supply chain means we get incredibly high-technology, state-of-the-art vehicles at a very decent price." Tariffs on Mexican-made vehicles will raise prices for U.S. consumers as well as Canadians, he said.

"Ultimately, the customers are going to say 'Dear Donald, some of this stuff doesn't make sense,'" because they won't like the price increases, Mr. Wildeboer said.

Liz Samms inspects brake lines destined for the U.S. made by Caledon Tubing, a division of Martinrea International, in St. Marys, Ont. on Monday December 5, 2016.

Glenn Lowson/For The Globe and Mail

A tour of Martinrea's Caledon Tubing plant in St. Marys, Ont., illustrates how the company – and the entire industry – has come to rely on NAFTA as a guiding system. Copper-coated low carbon steel that is used in brake fluid lines arrives at Caledon Tubing from Ohio, where it is roll formed into a double-walled tube about five millimetres in width. Then it's coated for corrosion protection, coiled and put into boxes that hold about 11,000 metres of tubing.

The brake tubing is then transported to Martinrea plants in Mexico, which in turn ship some of it back across the Mexico-U.S. border to General Motors Co. assembly plants in Arlington, Tex., and Fort Wayne, Ind. The tubing is installed on GM sport utility vehicles and trucks that are sold in the United States, but also cross the U.S.-Mexico and Canada-U.S. borders to be sold to consumers.

"It's amazing to follow that material from its infancy stage right to the end product, right to the end user, which could be us at the end of the day," said Peppi Rotella, assistant plant manager of Caledon Tubing.

Caledon Tubing ships 244,000 metres of brake tubing a week to Mexico, out of a total of 1.23 million metres sent to auto makers in the NAFTA countries.

Workers in the Magna plant in Puebla, Mexico, Wednesday, January 22, 2015.

Brett Gundlock / Boreal Collective / For The Globe and Mail

Parts flowing out of Mexico have helped Magna International Inc. remain competitive in the automotive seating business, chief executive officer Don Walker said. Seat covers are cut and sewn in Mexico because it's highly detailed, manual labour and it's hard to find people in Canada or the United States who want to do that work, he said. If costs were too high in Mexico to do that work and it had to be done in China, for example, transportation charges would increase the costs of the fabric that is shipped to a seating plant to be assembled into seats.

"The costs of the cut and sew would be higher, which means that the seat cost is higher, which means the vehicle cost is higher, which means the vehicle makers are less competitive," Mr. Walker said.

Mr. Trump has threatened to impose tariffs of 45 per cent on goods from China, but it's not clear if he would slap tariffs on vehicles imported from Europe or South Korea and whether that would lead to a World Trade Organization battle or whether he would adhere to a WTO rule requiring the United States to remove such tariffs. Mr. Walker pointed out that other industries such as electronics, the high-tech sector, transportation and materials suppliers have a stake in the debate because they depend on a competitive auto industry.

"If anything happens to make [auto] less competitive … jobs will go down," he says.

Magna was operating in Mexico before NAFTA came into force, but now has 30 plants in the country and 27,100 employees, more than it has in Canada or the United States. "I think it's been good for Canada and I think it's been good for the States," Mr. Walker says. "If it wasn't for NAFTA I think we would have fewer employees in both countries."

In 1999, five years after NAFTA came into force, Magna had 17,000 employees in Canada and 11,500 U.S. workers. Today, the parts maker employs 22,400 Canadians and 24,100 Americans. That's not entirely a result of NAFTA, but includes acquisitions made in the past two decades and a structural change in the industry as auto makers outsourced almost all of the parts manufacturing they once did themselves.

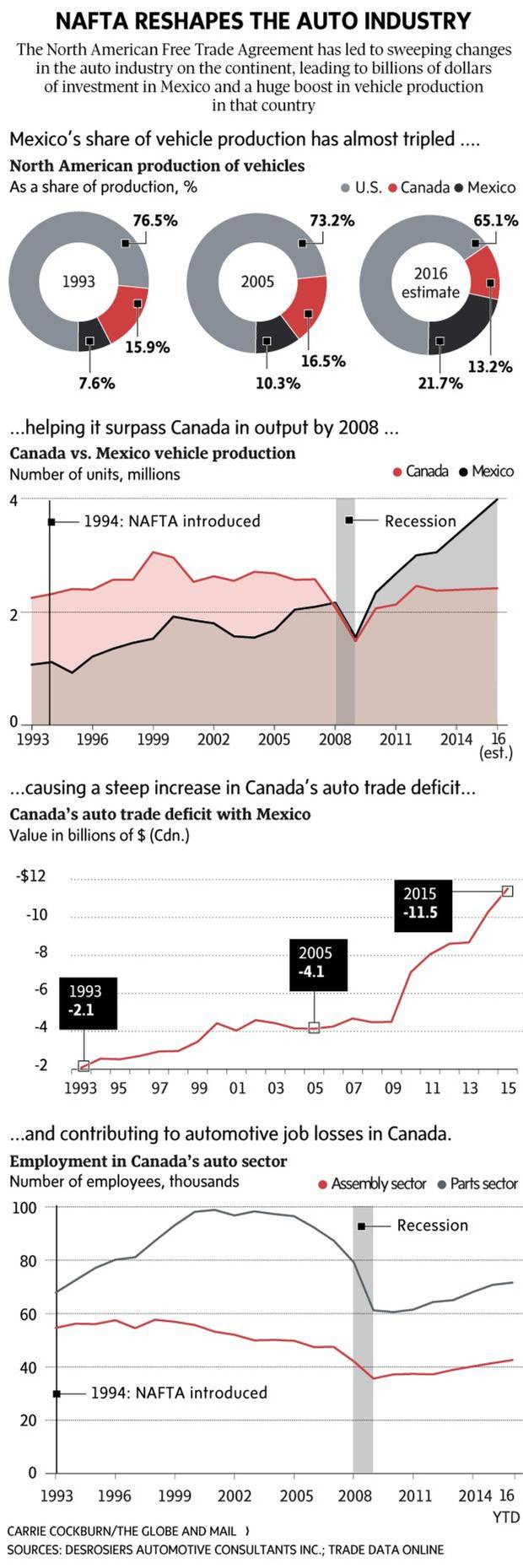

By several measures, Mexico has made the biggest gains as the auto industry in North America restructured itself to adjust to the trade deal. Mexico's share of North American vehicle production has almost tripled to 21.7 per cent from 7.6 per cent; vehicle production itself has more than doubled to 3.675 million annually and is projected to grow to five million by the end of the decade. The country's trade surplus with Canada soared to $11.5-billion (Canadian) last year from a pre-NAFTA level of $2.1-billion.

U.S. data released earlier this month show that the massive growth in auto production in Mexico will enable it to surpass Canada this year for the first time as an exporter to the United States. By those same numbers, Canada has been the biggest loser since 1994. Canada’s share of North American production has fallen more than the U.S. share on a percentage basis, while employment in the parts and assembly sectors in Canada and vehicle output has plunged since hitting a post-NAFTA peak in the late 1990s.

NAFTA is not the sole cause of the drop in Canada's vehicle production and employment. The trade deal coincided with a massive swing in consumer demand in North America away from the Detroit Three and to Asia and Europe-based auto makers. That shift led to the closing of several Detroit Three assembly and parts plants in Canada.

The lower employment numbers on the vehicle assembly side of the ledger are actually a positive indicator, argues industry analyst Dennis DesRosiers, president of DesRosiers Automotive Consultants Inc. Canada is now producing about the same number of vehicles it did in 1993 with 13,000 fewer workers, a signal that productivity has improved. NAFTA has also forced Canadian auto parts makers to become more competitive, Mr. DesRosiers adds.

One noticeable trend, however, is that Canada has not been obtaining its proportionate share of new automotive investment in North America. Between 2000 and 2010, auto makers invested about the same amount of money in Canada as they did in Mexico – $7.4-billion (U.S.). But the $21-billion spent in Mexico since then dwarfs the $4.2-billion spent on existing or new Canadian operations, data in a report done earlier this year by the Center for Automotive Research (CAR), an industry think-tank based in Ann Arbor, Mich., show. The CAR report notes, however, that this is not a result of closing U.S. plants and reopening them in Mexico.

"Much of the reduction in U.S. share [of output] is due to new production coming online in Mexico rather than shuttering and moving current U.S. production capacity out of the country," says the report, entitled The Growing Role of Mexico in the North American Automotive Industry. While Windsor Group, Magna, Martinrea, Linamar Corp., Exco Technologies Inc. and other Canadian parts makers have invested heavily in Mexico, the value of auto products imported into Canada from Mexico far exceeds Canadian exports to Mexico, as the trade data show.

A billboard welcoming Ford Motor Co. is seen at an industrial park in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, on January 4, 2017.

Christine Murray/REUTERS

The auto trade deficit with Mexico represents almost two-thirds of Canada's overall auto trade deficit of $18.5-billion (Canadian), said Jim Stanford, former economist for Unifor, which represents workers at the Detroit Three's Canadian plants. "That's far larger and more damaging than anything we ever had with Japan, even in the peak years," said Mr. Stanford, who is now a professor at McMaster University in Hamilton and director of the Centre for Future Work in Australia.

The bilateral trade deficit corresponds to the loss of 16,000 of the 40,000 jobs in the vehicle assembly and parts sector since 2001, he said. What Canada could seek in a renegotiation of NAFTA would be limits on such trade imbalances, he added.

But the jobs aren't likely to return to Canada – or to the United States for matter, which is Mr. Trump's goal in seeking to open up the agreement. The job market in Pulaski, a town of about 8,000 people, provides one explanation of why that is the case – it's hard to find people to fill existing openings.

At SaarGummi Tennessee Inc., two doors down from Tenneplas in an industrial park on the south side of Pulaski, a sign on the outside of the factory proclaims: "We're hiring. Walk-ins welcome." SaarGummi employs about 240 people making automotive sealing systems. In the north end of town, Magneti Marelli SpA is looking for people to work in its automotive lighting plant. Employment websites in the area say the auto parts company is offering $10.50 (U.S.) an hour to start, but will boost that with a $1 an hour bonus for anyone with perfect attendance in the first month. Hamburger chain Hardee's is running advertisements on a local country and western radio station seeking people to start at $8.50 an hour.

The Linamar Corporation innovation centre in Guelph, Ont.

Glenn Lowson/The Globe and Mail

The unemployment rate in Giles County, where Pulaski is located, was 4.5 per cent at the end of September, just under both the state and national jobless rates of 4.6 per cent. Even such states as Michigan, Ohio and Indiana, whose manufacturing sectors have taken some of the big hits in the southward shift of jobs, don't appear to have huge pools of excess labour. Indiana's rate of 4.2 per cent is lower than the national rate, while Michigan and Ohio are slightly above the national average at 4.9 per cent.

Mr. Henry said Tenneplas pays competitive wages, but the pay scale was not the reason for locating in Tennessee or for opening Mexiplas, the company's plant in Queretaro, which opened in 2011. "We've never chased the dollar in terms of wages," he said. "I'm not in Mexico to take advantage of cheap labour. I'm in Mexico because our customers are building vehicles in Mexico and they need us close to them."

He and other senior executives at Canadian parts makers point out that opening production facilities outside Canada also creates jobs at home in sales, engineering, design and other highly skilled functions. "Our IT department – we've got 30 people in that and all of that is in Windsor," Mr. Henry said. "That's all supporting all of our different manufacturing operations."