Some call it fishing, but it's more like threading a needle.

A Bell Canada technician in an apartment high above a Toronto street pulls a stiff metal wire out of a tube in the wall. The tech ties a string to the wire and pushes them both back in and through the ducts to a telecommunications closet on the same floor. A waiting technician grabs the end of the wire, unties the string and attaches it to a cable before sending the whole thing back through the tube to its destination in the home.

It's one of the final steps in rigging up an older apartment with state-of-the-art Internet service, and it will be repeated in every unit in the building – whether or not the residents are Bell subscribers. And the effort won't stop there.

As it races to keep up with faster Internet speeds offered by cable rivals such as Rogers Communications Inc., BCE Inc.-owned Bell is going to great lengths to build its network of the future. And Bell isn't alone. Canadian phone companies are more than three years into multibillion-dollar investments in the wires that connect them with their customers.

They have little choice but to improve those connections. The traditional home-phone business is dying a slow death and subscription TV is under huge pressure as more households opt to stream everything they want. Fast Internet has become the most important communications product by far and the company that wins the Internet race wins the home.

But while Canada's big telecoms rip up streets and buildings to offer speeds that meet or best their cable competitors, phone giants in the United States are waiting for wireless technology to bridge the gap between their networks and the last mile to subscribers' homes, raising fresh questions about the strategy playing out in Canada.

If you live in Toronto, you've likely seen Bell's plan in action. Technicians – their white-and-blue trucks often parked next to muddy holes surrounded by cracked pavement, orange pylons and caution tape – have been tearing up sidewalks and lawns for more than two years. The mess and inconvenience are all part of a $1.1-billion project to upgrade all homes and businesses in Toronto from old copper telephone wires – in place since the 1880s – to fibre-optic cables, which send information over tiny strands of glass at the speed of light. When complete, Bell will have laid more than 9,000 kilometres of fibre across the city.

"This is really a complete rebuild," BCE chief executive George Cope said in an interview. "It's like building the telephone network right from ground zero all over again."

A Bell utility vehicle is shown in Toronto on Sept. 19, 2017.

Christopher Katsarov/The Globe and Mail

Bell's investment comes as Canada's cable and phone companies are fighting an escalating battle. The rise of streaming services such as Netflix have taken a significant bite out of the traditional cable business and are placing increasing demands on networks just as the sheer number of connected devices – smartphones, laptops, tablets, smart appliances and health-tracking devices – is also on the rise. Add to the mix an increased use of applications such as video conferencing, file sharing, online gaming and 4K TVs, and it's clear the hunger for data will only intensify . By 2021, according to estimates from networking hardware company Cisco Systems Inc., global Internet traffic will be 127 times what it was in 2005.

The key to future profit growth is the Internet. To win that fight, Bell believes it needs a line into people's homes. And it needs to be fast.

Rogers, which has made less expensive and far less disruptive upgrades to its cable network, is already widely advertising gigabit speeds. In parts of the city where Bell has not installed fibre all the way to customers' doors, its speeds often top out at 100 megabits a second – at best, a tenth of the premium speed offered by its competitor.

The challenge for Bell is to reinvent itself to meet the need for bandwidth and speeds its customers don't even know they want yet.

"It's one gig today, and next year at some point you get into five gigs and then, as technology evolves and modems upgrade, ultimately, at some point folks tell me it will get as high as 40 gigs," Mr. Cope said.

Many people are already happy with download rates of 100 Mbps, which make it easy enough to stream music and movies instantly on multiple devices at the same time. So it can be hard to see how you would use speeds 50 – let alone 400 – times faster. Selling customers on the need for speed is one hurdle. Justifying the massive cost of rebuilding a network to shareholders is another.

Mr. Cope said the increase in speed will be used to support many more devices on the same connection. He admits that even five gigabits a second is "a lot of bandwidth for the average user at this point," but, "we're getting ahead of growth with a network built for the future. Provide the high-capacity bandwidth and innovators will use it to make the things that ensure people use that bandwidth even more. More and faster is always the way it needs to go with networks," he added.

To build this network, Montreal-based Bell, along with fellow telephone operator Telus Corp. – which sells residential services in the West and parts of Quebec – have both undertaken huge fibre to the home (FTTH) projects. Since 2014, Bell has invested $8.1-billion into its wireline business, while Telus has spent $5.2-billion – increases of 26 per cent and 30 per cent, respectively, over the previous three years. While that wasn't all spent on fibre upgrades, FTTH projects are the reason for the significant increases in spending.

It's a costly endeavour and it doesn't come without risk. The capital expenditures place demands on cash flow, making investors fret over usually rock-solid dividend payments. On top of that, the upgrades won't be complete for several years – and shareholders won't see a payoff for several more after that. And even after the telecoms have connected fibre cables to homes, they still have to persuade the people who live there to buy their services. But Bell and Telus insist they are making the right bet at the right time. Debt is cheap. And the race with cable companies to win the "bundle" of home services is already on.

"The telephone guys look at this as a generational thing," Bank of Montreal telecom analyst Tim Casey said. "The regulatory environment is stable, interest rates are at historically low levels, they monetized copper for 100 years, so now they're going to monetize fibre for 50 years. This is what they do."

Wired for war

Earlier this month, Mr. Cope stood on stage in a secondary ballroom at the Conrad New York, a business hotel just steps from the Lower Manhattan headquarters of Goldman Sachs Group Inc., which was hosting an annual investor conference. Upstairs, on the main stage, an executive from Major League Baseball was speaking.

A few hours later, Twenty-First Century Fox Inc. scion Lachlan Murdoch would make an appearance. But Mr. Cope – the only Canadian telecom CEO to speak at the three-day gathering of dozens of the world's most powerful media, communications and sports executives – still drew an audience of about 200 U.S. investors and analysts. He had the typical task of explaining Canada.

While Canadian phone companies are pouring billions into running wires into homes, U.S.-based giants are going a different direction entirely: wireless. Verizon Communications Inc. and AT&T Inc. have been aggressively testing 5G wireless technology that they hope to use within the next year or two to deliver home broadband service. The new "fixed wireless" technology uses very high-frequency radiowaves – shorter wavelengths that carry a lot of data, but don't travel far. To make it work, U.S. telecoms will need to install a dense blanket of small cellular sites in urban areas. But they won't have to dig up yards and sidewalks.

It's not that the Canadian telecoms aren't interested in 5G technology, Mr. Cope said in New York. They do plan to use it for mobile service, but just don't see it as the best solution for connecting to customers' homes.

"In the United States, as I understand it, some of the major carriers are planning to roll out 5G from a fixed perspective. And to have what is talked about as a one [gigabit a second] wireless fixed mobile service. I get it," he said. However, "in Canada, we are doing fibre to every one of those premises. And so, you will, in all likelihood, not see a fixed 5G service in the urban markets – certainly not from us."

"The economics [for Bell] don't seem extraordinary to me," a skeptical audience member said, asking the Bell CEO to walk him through the financial case for FTTH and launching Mr. Cope into a back-of-the-envelope-style explanation that most Canadian telecom analysts could recite by heart at this point.

George Cope, president and CEO of BCE, speaks at the company’s 2017 annual general meeting.

Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

Assuming it can win its targeted 50-per-cent market share in the places where it rolls out fibre, Mr. Cope said the cost of connecting each customer's home averages out to about $4,000. But the investment is in the home itself, he said, which will be connected to fibre services long after the current occupant moves on.

In addition to Internet service – which brings in $60 to $65 a month – Bell hopes to sell customers on its TV offerings, charging an additional $40 to $60 a month. Mr. Cope figures Bell can make about $120 for every user in this scenario.

Mr. Cope also thinks Bell has an edge thanks to its ownership of Bell Media, the biggest media company in the country, which brings down costs on content for the TV service – and helps Bell compete with Rogers and Quebecor Inc.'s Videotron, which also own media businesses of their own.

Operational costs are also lower with fibre, he says, because of fewer service calls.

"That's the model – that's why we think it works," Mr. Cope concluded as his session wrapped up.

But analysts say the reason for the rush to fibre goes beyond financial forecasting: There's simply no time to wait for 5G.

"Rogers is stealing customers from Bell in Toronto because they offer higher speeds," Desjardins Securities analyst Maher Yaghi said in an interview. "If the telephone companies don't make the fibre investment, they're going to lose a lot of customers. That is what is facing them."

Rogers, which is Bell's primary competitor in the crucial Ontario market, started offering gigabit speeds in Toronto in late 2015 and now sells it across its entire service footprint, aggressively promoting its range of Internet products to help offset a weak TV product. That strategy gave the company a noticeable boost, leading to a 4.7-per-cent increase in its total base of Internet subscribers last year.

Over the first half of this year, Rogers attracted 41,000 additional Internet customers, an increase of 46 per cent over the first half of 2016. Bell, which is not yet able to widely market its FTTH service in Toronto, added just 16,000 broadband subscribers – 40 per cent fewer than the same period last year.

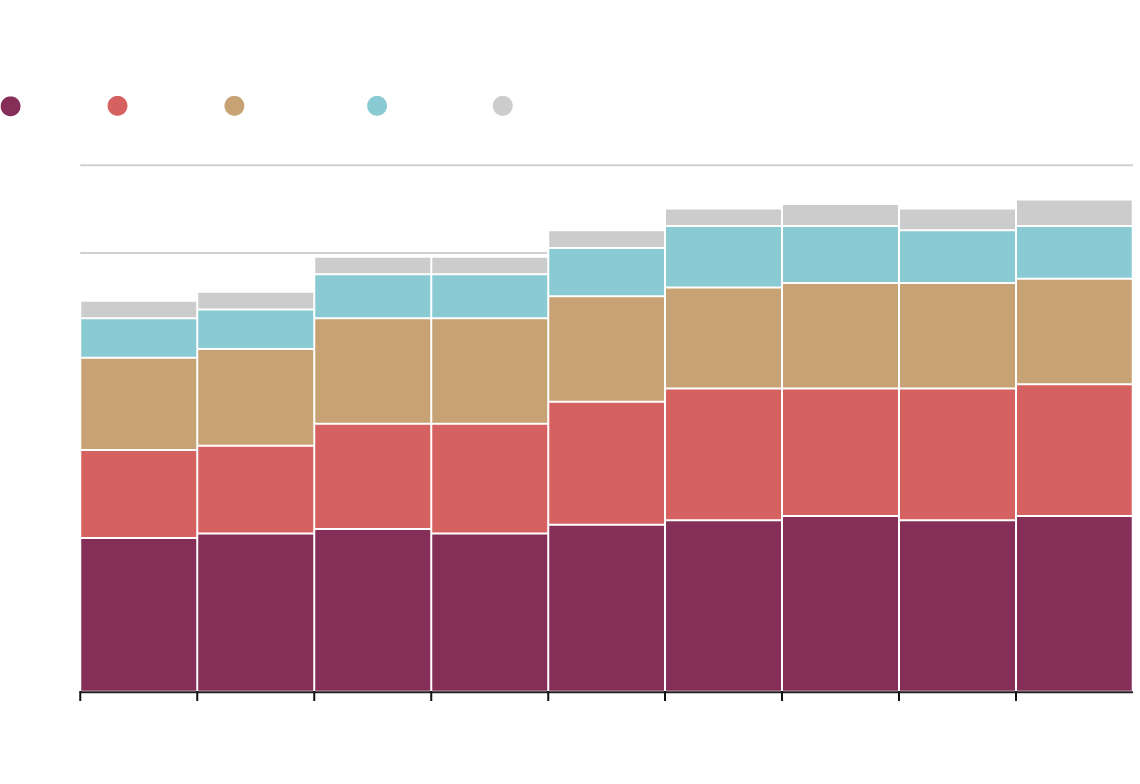

And it's bigger than Rogers versus Bell. In many ways, it's an extension of a decades-long battle that has pitted cable against telephone in Canada's telecommunications landscape. Moody's analyst Bill Wolfe said there's an "investment race emerging between Canada's cable and phone companies."

Cable and telecom capital expenditures

Estimates for 2017 and onward

Rogers

Shaw

Cogeco

BCE

Telus

$12

In billions

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.5

0.4

0.4

0.4

10

1.2

1.4

1.2

1.4

1.1

0.4

0.4

1.0

1.0

0.9

2.4

2.4

2.4

0.9

2.3

8

2.4

2.4

2.4

2.2

2.1

6

3.0

2.9

3.0

3.0

2.8

2.4

2.5

2.0

2.0

4

4.0

4.0

2

3.9

3.9

3.8

3.7

3.6

3.6

3.5

0

2012

2014

2016

2018

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: CAPITAL IQ, ALTACORP CAPITAL

Cable and telecom capital expenditures

Estimates for 2017 and onward

Cogeco

BCE

Telus

Rogers

Shaw

$12

In billions

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.5

0.4

0.4

0.4

10

1.2

1.4

1.2

1.4

1.1

0.4

0.4

1.0

1.0

0.9

2.4

2.4

2.4

0.9

2.3

8

2.4

2.4

2.4

2.2

2.1

6

3.0

2.9

3.0

3.0

2.8

2.4

2.5

2.0

2.0

4

4.0

4.0

2

3.9

3.9

3.8

3.7

3.6

3.6

3.5

0

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: CAPITAL IQ, ALTACORP CAPITAL

Cable and telecom capital expenditures

Estimates for 2017 and onward

Telus

Rogers

Shaw

Cogeco

BCE

$12

In billions

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.5

0.4

0.4

0.4

10

1.2

1.4

1.2

1.4

1.1

0.4

0.4

1.0

1.0

0.9

2.4

2.4

2.4

8

2.3

0.9

2.4

2.4

2.4

2.2

2.1

6

3.0

2.9

3.0

3.0

2.8

2.4

2.5

2.0

2.0

4

2

4.0

4.0

3.9

3.9

3.8

3.7

3.6

3.6

3.5

0

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: CAPITAL IQ, ALTACORP CAPITAL

The major cable players in Canada all have wireless businesses now – Rogers, Quebecor and Eastlink in the East and Shaw Communications Inc. in the West – and Mr. Wolfe wrote in a report this spring that this dynamic plays into the push for phone companies to invest in fibre.

"Canadian cable companies' wireless capabilities force Canadian [phone] companies to – ironically – spend money to enhance their fixed-line capabilities. Otherwise, the [phone] companies risk the cable companies eventually emerging as winners, with growing wireless franchises and with fixed-line superiority allowing share growth in that market as well," he said.

"As Internet streaming-based programming increasingly replaces television, the quality of the Internet connection will become paramount, requiring investment to assure best-in-class speed, volume, reliability and cost of service."

Pulling fibre directly into customers' homes isn't the only way to improve speeds. For years, telephone companies installed fibre throughout their "core" networks, building into neighbourhoods and getting closer to people's homes. Known as fibre-to-the-node (FTTN), this technology still uses copper telephone wires for the end of the last mile, but it is faster than the original high-speed Internet service that telecoms offered (digital subscriber line or DSL). It also let telecoms offer Internet protocol television (IPTV), which chipped away at the dominance in the TV market that cable companies previously enjoyed.

But cable operators have also upgraded their infrastructure, pushing fibre-optic cables through their core networks and deeper into neighbourhoods and using software improvements to get faster speeds out of their cable lines, outpacing what telephone companies can offer without fibre all the way to the home.

Even with FTTH, Mr. Yaghi said he thinks Bell's goal of winning 50 per cent of the market "is an aggressive target," considering the competition from cable players, satellite options and smaller competitors who buy wholesale access to the incumbent cable and phone companies' networks at regulated rates.

"They have to try and get the [50-per-cent market share], but I think it's a tough objective to maintain over the long term," he said. Still, he estimated Bell and Telus will "get at least 40-per-cent market share in the markets that they're building up and that they'll be able to get $130 or more in revenue per customer per month."

In a report last year, Mr. Yaghi predicted that once the telecoms have covered about 60 per cent of their base with FTTH, they might scale back and consider wireless technologies such as 5G to connect remaining customers with higher-speed broadband.

That's not out of line with Telus CEO Darren Entwistle's approach to the 5G versus FTTH debate.

"Within Canada, it's not that we're ignoring what could potentially be a nice economic-access method to complement what we're doing in terms of building fibre to homes and businesses," Mr. Entwistle said on an earnings call in August.

"But for us right now, we continue to pursue direct fibre connectivity.

"We are taking an accelerated roll out to fibre, which we think is the right thing for us to do," he added, pointing to the low cost of borrowing and regulatory conditions that support and reward companies for investing in their infrastructure.

Mr. Yaghi agrees. The low-interest-rate environment gave them ample room to manoeuvre a couple of years ago, though he expects they will have less flexibility in the coming years.

"Imagine having to explain to investors you're loading up on leverage when interest rates are going up."

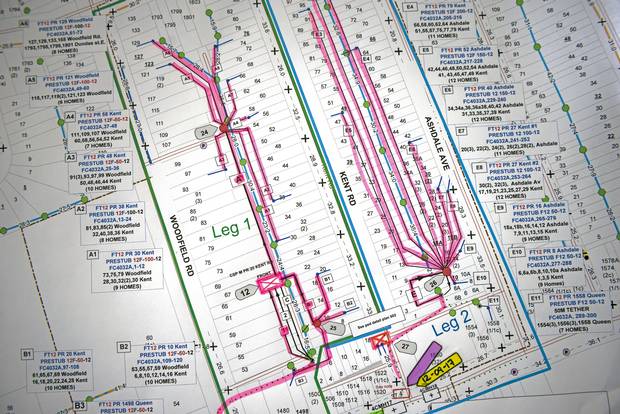

A map of city areas where fibre-optic cable is being installed.

Christopher Katsarov/The Globe and Mail

On the front line

Long before Bell technicians show up in apartment buildings or back alleys to string fibre, teams of engineers divided into groups of four plot out each part of the City of Toronto, devising plans to access and connect about 350 homes at a time. Jamie Nightingale, director of network provisioning, supervises one part of the effort at a Bell office on Wynford Drive, where the walls are lined with large neighbourhood maps marked up with slashes of neon highlighter and sticky notes.

"When we rolled out Toronto, they broke the city up into little pieces – a patchwork to put together," he said. "So each group of four is accountable for one area and they figure out how to get the fibre from our central office out to the customers."

Central offices, often non-descript brick buildings, are scattered throughout the city and house telephone-switching equipment, reams of old copper telephone wires and rows of blinking computer servers. They offer connections to the broader Internet, and it's from these offices that fibre-optic wires snake under roads, manholes and lawns, eventually connecting individual houses or entire apartment buildings.

"We've got to contact owners, work with cities for municipal consent to access right of ways and work with utility companies to get permission from them as well," Mr. Nightingale said, adding that lighting up each area with fibre "can take from three months on a really good one to up to 71/2 months on some outliers."

In some cases, the city may have just repaved a street or sidewalk and issued a moratorium on digging it up for a number of years, meaning the Bell engineers have to figure out a different way to access the building.

The company also has to carefully manage its relationship with the public. Barclays Capital analyst Phillip Huang noted in the spring that Bell was hard at work in many "prime neighbourhoods in the city such as Lawrence Park, Kingsway and the Beaches." Homeowners are often amenable to the construction, he said, seeing it as a "free enhancement to their property values," but residents in such neighbourhoods also tend to expect "'white glove' service on manicured lawns."

Still, as it progresses, Bell has been increasing the pace of its roll out, and Mr. Cope said "the goal here is to hopefully cover 700,000 or 800,000 additional homes per year … and ultimately get to 80 per cent of our footprint over time."

Bell says it will have connected most of the homes and businesses in Toronto by early 2018 and will begin mass marketing its gigabit-Internet service. It can't justify such a campaign before reaching about 60 per cent of premises.

The company has also been laying fibre in Montreal since March, a further $854-million investment, and says it is on track to complete 40 per cent of its total FTTH build by the end of this year, with 3.7 million homes connected.

Earlier this year, it launched a cheaper, app-based TV service known as Alt TV to appeal to TV cord cutters. It's a strategic move to keep at least some TV revenue and, crucially, get into the home with an Internet subscription.

But the company won't have an easy ride. Early next year is also right around the time that Rogers plans to launch a revamped television service (using IP-based technology licensed from Comcast), and the cable company is likely to launch a renewed campaign to sell TV while continuing its aggressive marketing of Internet.

Bell's push in Toronto and Montreal came after starting with Quebec City in 2012 (Bell Aliant, which BCE now owns, has also rolled out FTTH service widely in its Atlantic Canada service footprint).

"We chose Quebec City because it was big enough to kind of sink our teeth into, but small enough that it wasn't a massive build like Toronto or Montreal," said Stephen Howe, an executive vice-president and chief technology officer with Bell. Quebec City was also appealing, he said, because about 95 per cent of the network is "aerial," meaning the wires are connected to telephone or hydro poles, making it easier and cheaper to upgrade than underground cables. Toronto is "probably, at best, 60-per-cent aerial."

Wiring up Canada's biggest city – complete with its signature traffic congestion and numerous utilities that must be consulted each time Bell puts a shovel in the ground – is a challenge, Mr. Howe said. "It certainly is not an easy project, but we're very pleased with our progress to date."

Telus, which started its FTTH program in 2013, took a different approach to its build, beginning with eight small communities in Alberta and British Columbia with populations of 2,000 to 20,000, explained Tony Geheran, executive vice-president and president of broadband networks. It has now completed 75 communities and has 25 more under way, including larger cities such as Vancouver, Edmonton and parts of Greater Victoria.

"What we did was fairly unusual. We started with a relatively small investment of $50-million to build eight communities. We were looking at them as pilot incubators to work out processes, try techniques and see what worked and didn't work," Mr. Geheran said, adding that what they learned along the way changed how Telus works with vendors and contractors and how it markets the new service to consumers.

He said the personal touch involved in explaining the construction to homeowners often helps when it comes time to convert them to customers. "Our team members are in the community not only doing the physical build but also knocking on every door and every business, explaining the process, getting permission to place fibre to the premise. And once the fibre is placed, we come back and then we talk about the service options."

Telus has already connected about 1.26 million homes with FTTH, about 42 per cent of its service footprint, and plans to near 50-per-cent coverage early next year. That puts it further along, relatively speaking, than Bell, which has a much bigger base to cover.

Both companies aim to get permission to install fibre from every homeowner in their service area, assuring them there is no commitment to purchase service down the road – but also hoping to pique people's interest in super-fast broadband.

Bell and Telus also try to cultivate positive relationships with municipalities, given the disruptive and messy work they have to perform. Bell committed to provide gigabit fibre service to United Way community hubs across Toronto. When Telus announced plans to build fibre service in Edmonton in 2015, the company donated $120,000 to the city's public library.

With the capital demands of its fibre build combined with spectrum purchases, Telus's ability to generate cash has come under pressure, but Mr. Entwistle said the company plans to return to growth in free cash flow by mid-2018 and stay there. However, he has also warned investors not to expect capital investments to slow to zero, as Telus still needs to keep spending on fibre. Mr. Geheran said the company will invest about $900-million on the fibre program this year, about the same as last year.

"It's very expensive. It's a massive undertaking. But we are very confident based on the results that we're seeing that it's the right long-term bet," Mr. Geheran said. "It resonates really well with customers."