The electric locomotive 2EV120.

In a city on the Volga River named after one of the authors of The Communist Manifesto, a factory is producing a new line of locomotives using Bombardier Inc. technology – an effort financed by a Kremlin-controlled bank that is on Canada's sanctions list over the war in Ukraine.

Bombardier Inc. issued no press release in the summer of 2015 when its partners rolled out the prototype for the Traxx 2EV120 locomotive, an engine designed for the wider-gauge rail tracks used in Russia and the rest of the former Soviet Union. Nor did the company's annual reports to shareholders in 2015 and 2016 mention the new locomotive – which is nicknamed the Prince Vladimir. Bombardier's only public confirmation of the project has been a 48-word statement on its Swiss website that announced the engine's first test run.

The Kremlin-run VneshEconomBank, better known as VEB, says it bankrolled the entire $200-million (U.S.) cost of designing the Prince Vladimir via a loan given by its subsidiary, VEB-Leasing.

VEB has been on Canada's sanctions list since July, 2014, when it was among the Kremlin-connected institutions Ottawa targeted as punishment for Russia's seizure and annexation of the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine earlier that year. VEB is considered a foreign policy tool of the Russian state, and the chairman of its supervisory board, by law, is always the Russian prime minister.

VEB also features in the multipronged investigation into the alleged connections between U.S. President Donald Trump's administration and the Russian government. Jared Kushner, Mr. Trump's son-in-law and key adviser, has admitted he met privately with VEB head Sergei Gorkov before Mr. Trump's January inauguration.

The Montreal-based Bombardier is already embroiled in a sanctions-related controversy after admitting it lobbied Ottawa to keep former Russian Railways boss Vladimir Yakunin, a long-time ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, off Canada's sanctions list.

Earlier this year, prosecutors in Sweden detained three executives in the Stockholm office of Bombardier Transportation on suspicion of "aggravated bribery" in connection with the sale of railway signalling systems in Russia and other former Soviet states via a third party, Multiserv Overseas Ltd., that was described in internal Bombardier e-mails as "a vehicle to siphon monies from the public sector into private pockets."

Officials attend the 2015 opening of the locomotive plant in Engels, Russia.

The partnership question

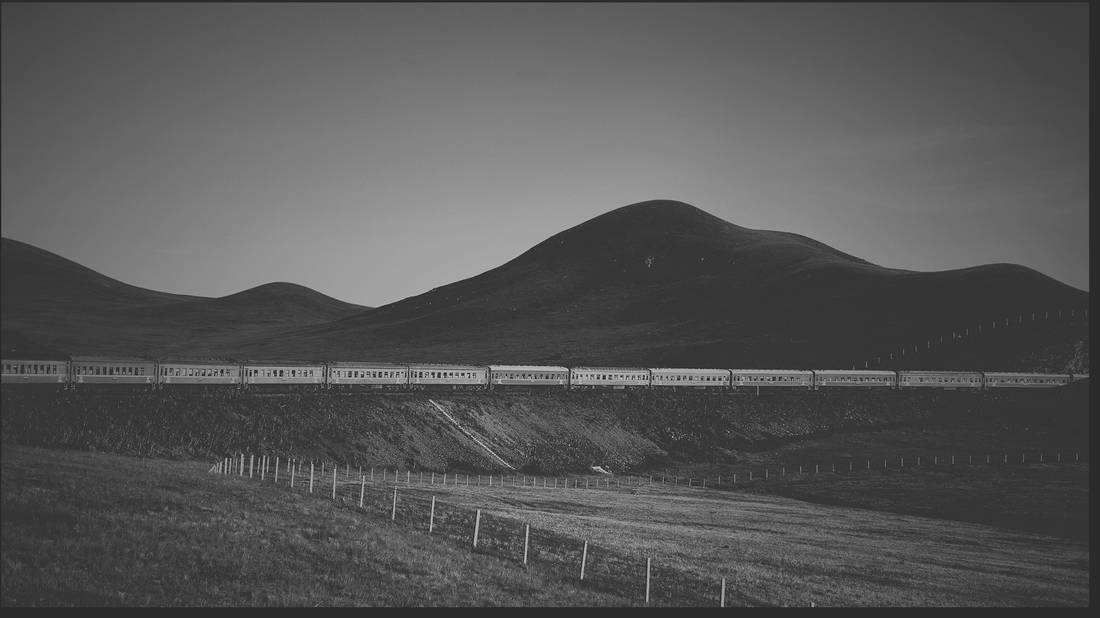

The Prince Vladimir locomotives are manufactured at a factory in Engels, an industrial city named for Friedrich Engels, one of the authors of the Communist Manifesto, about 1,000 kilometres southeast of Moscow on the Volga River, in the Saratov region. The first two models of the new locomotive have been painted in the red-and-white colours of the state-owned Russian Railways, although the railway has yet to buy any of them.

Railway experts say the Prince Vladimir is Bombardier's push to break into the potentially lucrative market for rail equipment in Russia and the former Soviet Union, which until now has been dominated by Germany's Siemens AG and France's Alstom, both of which have their own Russian partners.

The Prince Vladimirs are produced by a Russian firm called First Locomotive Company (FLC), which describes itself on its website as a "part of a joint project of Russian investors and Bombardier Transportation." Bombardier Transportation is the Berlin-headquartered railway arm of the Montreal-based Bombardier Inc.

Mike Nadolski, Bombardier's vice-president of communications and public affairs, said Bombardier's role is less direct than FLC's description.

Bombardier Transportation, he said, owns just 15 per cent of a Swiss entity known as First Locomotive Holding, which in turn owns the Russian-registered FLC. Mr. Nadolski said FLC has a license agreement with Bombardier Transportation that allows it to use Bombardier's Traxx locomotive technology.

"It would be incorrect to say that Bombardier has a direct partnership with VEB related to the Engels factory," Mr. Nadolski said in response to e-mailed questions from The Globe and Mail. He added: "We believe that all of Bombardier's actions are fully compliant with the Canadian sanction regulations."

Both VEB and the Moscow office of First Locomotive Company declined to answer questions about the enterprise. A Russian source with direct knowledge of the deal said the project was brought to Bombardier "by a private investor," and that Bombardier Transportation had been satisfied, after conducting an assessment, that its relationship with VEB was compliant with sanctions law.

"The due diligence was done," the source said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Mr. Nadolski would not identify who controls the remaining 85 per cent of First Locomotive Holding, although its Russian subsidiary appears to have political connections. The chief executive officer of FLC is Alexander Strelyukhin, a 58-year-old who also serves as both the deputy head of the Saratov regional government and the leader of the local branch of United Russia, the political party of Mr. Putin.

First Locomotive Holding lists its address as 29 Lowenstrasse, a mid-rise office block in the centre of Zurich. On the fourth floor of the building is a law firm headed by Thilo Pachmann, a Swiss lawyer who is the only listed director of First Locomotive Company. Mr. Pachmann did not respond to requests for comment.

Another partner in producing the Prince Vladimirs is the Engels Locomotive Factory that builds them, which is itself 15-per-cent owned by VEB Leasing. The Russian business newspaper Kommersant reported in 2014 that the rest of the shares in the factory were controlled by a pair of Cyprus-registered shell companies, Volcam Trading and Rafelar Holdings.

Corporate ownership records seen by The Globe and Mail show that Volcam Trading is itself owned by a company registered in the British Virgin Islands, while Rafelar Holdings is owned by another shell Cypriot company controlled by Said Gutseriev, the oldest son of Mikhail Gutseriev, an oligarch close to Mr. Putin.

The sanctions question

The Canadian government would not give a direct answer when asked whether it believes Bombardier is offside on sanctions by working on a project financed by VEB, and the relevant sanctions language is ambiguously worded.

The most prohibitive Canadian sanctions are deployed against people and entities named on Ottawa's Schedule 1 list, those who bear responsibility for the situation in Ukraine. For instance, it is illegal for Canadian companies to finance or receive financing from Russians listed on Schedule 1. VEB is on Schedule 2 of Canada's sanctions list, which covers people and entities that work for or provide services to those on Schedule 1.

Global Affairs Canada spokesman Austin Jean said the rules prohibit Canadians from "dealing in new debt of longer than 30 days maturity in relation to persons listed in Schedule 2." Mr. Jean said the rules likewise prevent Canadians from "dealing in new securities in relation to persons listed in Schedule 2."

Milos Barutciski, a trade-law expert with Bennett Jones in Toronto, said that Canada's Russian sanctions are generally interpreted as prohibiting Canadians from lending money to entities listed on Schedule 2 of the measures. The sanctions, he said, do not prevent Schedule 2 institutions from lending to Canadian companies.

The language of the Canadian sanctions law was borrowed from the U.S. Treasury Department's sanctions law targeting VEB. The United States, Canada and the European Union collectively applied sanctions against VEB and five other Russian banks as the crisis in Ukraine escalated in the summer of 2014.

The initial deal to have VEB fund the development of the new locomotive was announced in June, 2013, nine months before the annexation of Crimea and the subsequent tit-for-tat sanctions. (Canada has slapped sanctions on more than three-dozen individuals and institutions seen as having played a role in the Kremlin's policy towards Ukraine, Moscow has retaliated by barring 13 Canadians – including Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland – from entering Russia. Moscow's sanctions also ban most Western agricultural products.)

VEB often finances ventures that are dear to the Kremlin. It lent billions for the building of sites for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, a pet project of Mr. Putin's and the most expensive Games ever held.

The bank also lent hundreds of millions of dollars to Russian-controlled companies that bought up industrial assets in eastern Ukraine before the outbreak of the conflict. The bank's chief executive, Mr. Gorkov, is a graduate of the FSB Academy, which produces Russian spies.

Company representatives take part in TransCaspian 2015, an international exhibition of transport, transit and logistics, hosted in Baku, Azerbaijan.

https://1-plk.com

The climate in Russia

Bombardier has attempted to maintain its business in Russia even as relations between Ottawa and Moscow have plunged near an all-time low, but the company's fortunes have taken several heavy blows. In 2014, as the sanctions war began, Bombardier's aerospace division was forced to suspend plans to build an assembly plant for its Q400 turboprop planes in Russia. A $3.4-billion (U.S.) contract to sell Q400s to Russian buyers was also frozen.

The company has struggled financially in recent years, and received $372-million (Canadian) in repayable loans from the federal government earlier this year to help fund aerospace projects. The troubles facing its railway business were highlighted in May, when China's mammoth CRRC Corp. won a contract to build commuter trains in Bombardier's home city of Montreal with a bid that was 30-per-cent cheaper than Bombardier's.

Bombardier is reportedly close to a deal with Siemens for the two companies to tie their railway divisions together in an effort to better compete with CRRC. The agreement would reportedly create two new joint ventures, one for the rolling stock business, the other for the signalling divisions.

Bombardier would have a share of just over 50 per cent in the new rolling stock company, with Siemens owning about 80 per cent of the signalling joint venture, according to a Reuters report. But the deal is not a sure thing.

It is unclear what impact, if any, a Bombardier-Siemens tie-up would have on the effort in Engels.

Russia has long been an important emerging market for Bombardier, but sales have slumped there too, from $505-million (U.S.) in 2014 (rail and aerospace combined) to $268-million in 2015 and $255-million last year.

The company's largest investor, Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, has expressed reservations about the investment climate in Russia, fuelled by worries about corruption, sanctions and inconsistent application of the law. Caisse chief executive Michael Sabia told reporters earlier this year that "Russia is a country where we're not going anywhere near right now." (He was speaking generally, and not specifically about Bombardier's activities.)

The Caisse acquired a 30-per-cent stake in Bombardier Transportation in late 2015.

First Locomotive has struggled to find a market for the Prince Vladimir. (The nicknamed refers to Vladimir the Great, a figure revered – by Mr. Putin among others – for bringing Orthodox Christianity to Russia and Ukraine in the 10th century.)

Shortly after the sanctions war began in 2014, Valentin Gapanovich, the vice-president of Russian Railways, said he did not see the need for the locomotives Bombardier and its partners were planning to produce in Engels.

The Russian source with direct knowledge of the project said the decision to build the Prince Vladimirs was always "speculative" based on the perceived needs of Russian Railways. No deal was ever in place for the state-controlled railway to buy the Bombardier locomotives, he said.

The effort to produce the Prince Vladimirs continued anyway, leaving Bombardier and its partners scrambling to find other buyers. In a 2015 press release, First Locomotive Company said the first 15 Prince Vladimir locomotives would be sold to Armenia, Azerbaijan and Iran.

Officials in Ukraine say there has also been an active attempt – via an intermediary company – to sell the Prince Vladimir locomotives in Ukraine.

"These locomotives are still in the process of certification in Russia, but they have no prospects there," said a senior Ukrainian official with direct knowledge of the country's efforts to upgrade its locomotive fleet.

The official said the intermediary company was trying to disguise where the locomotives had been made, but Ukrainian officials quickly recognized that they had identical specifications to the Prince Vladimir.

"Ukraine has very difficult relations with Russia right now, and we cannot buy locomotives manufactured in Russia," the official said, adding that he nonetheless did not rule out that the mystery company could yet win the bid given the corruption-riddled nature of Ukraine's national railway company, Ukrzaliznytsia.

"It depends if Ukraine decides to be precise about where these locomotives are coming from," the official said. He added that several "mid-level employees" of Ukrzaliznytsia were lobbying for Ukraine to buy the equipment, despite its origin.

The apparent attempts to sell the Prince Vladimir locomotives in Ukraine come despite a memorandum of understanding between Bombardier and Ukrzaliznytsia – in which the two parties agreed to explore the possibility of jointly producing locomotives inside Ukraine – that was signed during Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's state visit to Ukraine last year.

Bombardier Transportation has faced mounting questions in recent months over its operations in Russia and the former Soviet Union. Sweden's anti-corruption prosecutors have thus far focused their investigation into suspected bribe-paying on a single 2013 contract to install rail signalling systems in Azerbaijan, but have suggested the inquiry could widen.

The World Bank, which provided 85 per cent of the funding for the Azerbaijan deal, is also in the midst of auditing Bombardier's Russian and Swedish offices in connection with the project.