It turns out there is something on which even Republicans and Democrats can agree: Facebook Inc. needs to grow up.

At 13 years old, the world's largest social network – with 2.07 billion monthly active users, a stock market value of $517-billion (U.S.) and revenues that are fast approaching $1-billion per week – is a very rich, powerful, secretive teenager. Suddenly, it finds itself being called to account for how it is using that power, and for how it often fails to stop those who want to use its platform for evil, and perhaps illegal, purposes.

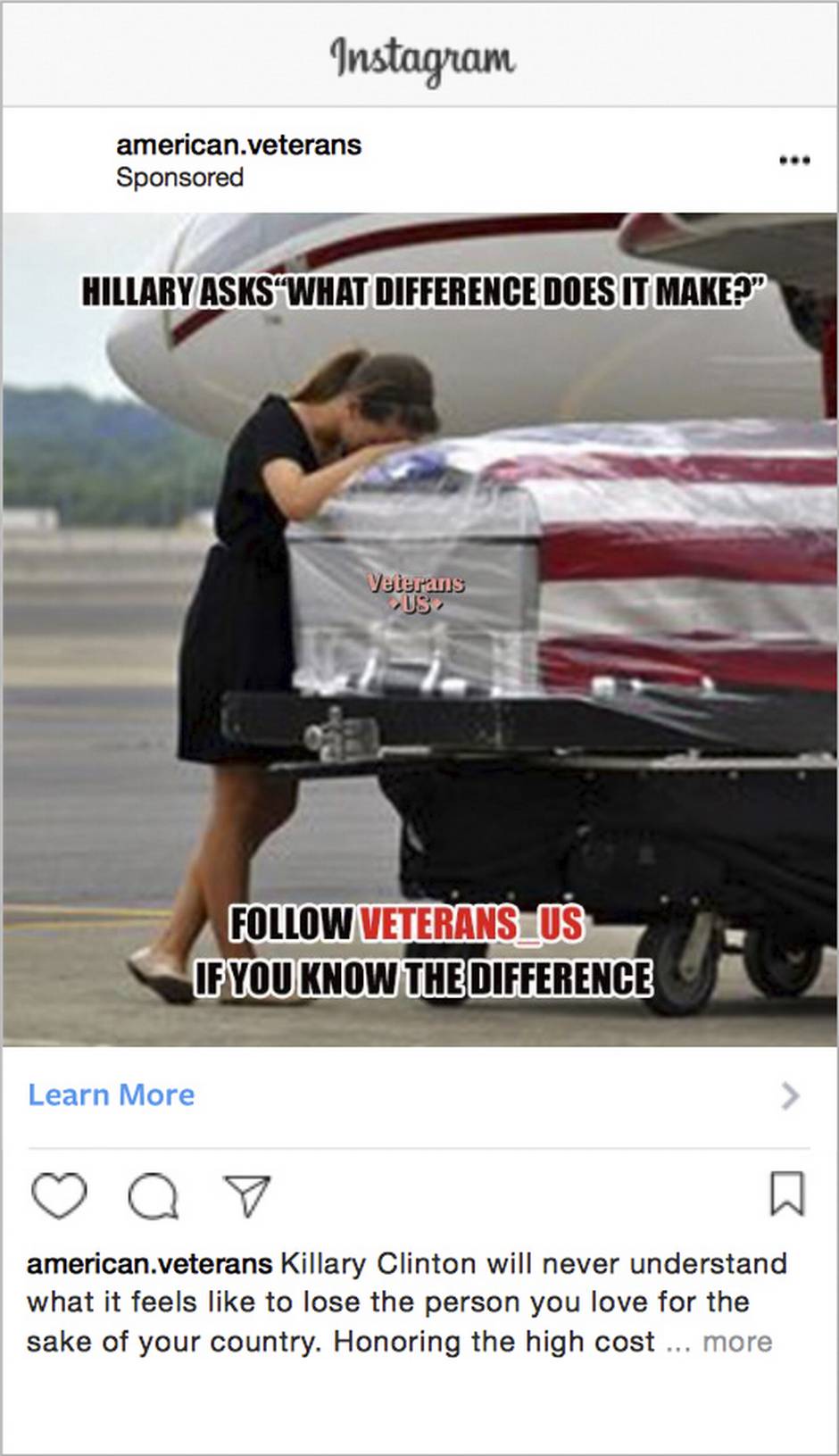

Facebook's algorithms – which reward and promote posts that keep users sharing and caring and "engaging" – can shape public debate and change the fate of a business overnight. But those same tools have also been used to spread fake news, amplify hate speech and connect bigots of all kinds. They were used by agents of the Russian government to stoke division and help tilt the 2016 U.S. presidential election toward Donald J. Trump. That election, of course, was won by Mr. Trump last November on the strength of narrow victories in a handful of swing states, despite losing the popular vote by nearly three million.

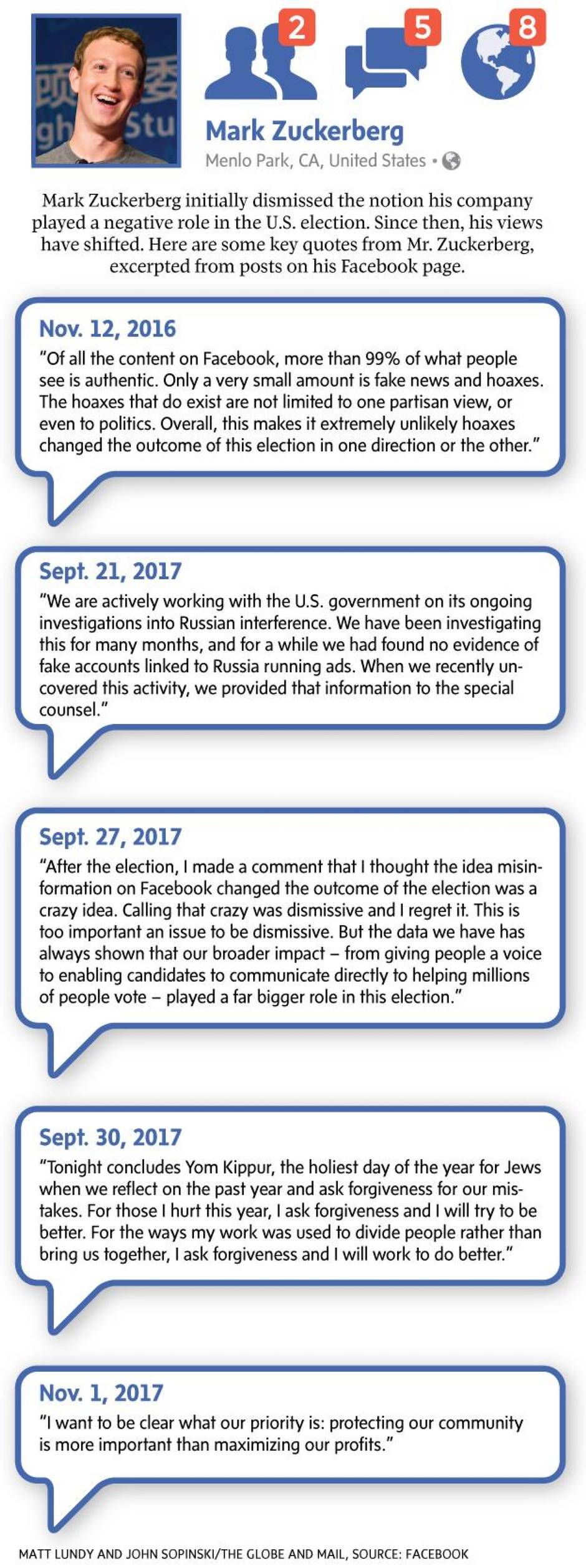

"Personally, I think the idea that fake news on Facebook, of which it's a very small amount of the content, influenced the election in any way is a pretty crazy idea," founder Mark Zuckerberg said right after the vote.

It doesn't seem crazy at all now.

Given Facebook's influence, an increasing number of marketers, courts, regulators and legislators around the world are no longer excusing its mistakes and blind spots as youthful ignorance. Governments are calculating the social costs of an unaccountable publishing platform and are lining up to wrest back some of the control that Facebook has collected.

The regulations being shaped today – and the way Facebook responds – could dramatically affect the shape of the company and its business model in the future.

The exact shape of those rules is still to be determined. But the likelihood that Facebook can avoid them, and continue operating in an almost-unregulated environment, is diminished after what was one of the most brutal weeks in the company's history.

A set of dramatic U.S. Senate and House hearings provided ominous signs of future regulatory action. Facebook, Twitter Inc. and Google Inc. executives were called in to explain what they knew about Russian interference in the U.S. election and describe the steps they are taking to prevent such interference in the future.

In many ways, it all started with Facebook's refusal to acknowledge any negative role in the election. After Mr. Zuckerberg's breezy dismissal of fake news as an election factor, journalists and lawmakers dug up more and more links to challenge his assertion.

The facts began to dribble out. In September, Facebook revealed that, yes, Russian agents had purchased more than 3,000 pro-Trump ads between 2015 and 2017, which may have been seen by more than 10 million people. On Sept. 21, Mr. Zuckerberg released a video in which he said he would work hard to defend democratic values. Then, a week later, he wrote a post that concluded: "Calling that [the Russian/fake news allegations] crazy was dismissive and I regret it."

The latest round of hearings may be cause for more regrets.

All three companies sent lawyers, not their chief executives, a decision on which Republican, Democratic and independent senators remarked caustically. Colin Stretch, Facebook's general counsel, took the lead in answering questions and revealed that perhaps almost 150 million Americans saw some of the more than 80,000 posts – not all of them ads – that Russian agents had placed on Facebook and its photo- and video-sharing service, Instagram.

Democratic Senator Dianne Feinstein – who is from San Francisco and about as tech-friendly a politician as you'll find – sharply rebuked Mr. Stretch's performance: "I went home last night with profound disappointment. I asked specific questions, I got vague answers. And that just won't do.

"We are not going away, gentlemen. And this is a very big deal," she said. "You created these platforms … and now they're being misused. And you have to be the ones who do something about it – or we will."

In a call with investors on Wednesday, Mr. Zuckerberg said his company was being pro-active about preventing abuse of its platform. "Even without legislation, we're already moving forward on our own to bring advertising on Facebook to an even higher standard of transparency than ads on TV or other media."

Prior to the hearings, Facebook announced it would begin testing disclosures on all its ads – in Canada first and in the United States and other countries later – so users will be able to look at all the ads a company or group is paying for on the platform. This is a vital issue for political campaigners who have complained that Facebook's ad-targeting process often meant there was no way to identify what kind of advertising is being done and at whom it is targeted. This voluntary transparency effort also pledges to develop a searchable archive of all U.S. election ads starting with next year's midterm elections.

In a critique of Facebook's promises, Tim Wu, Columbia University professor and author of a critical book aimed at the advertising industry called Attention Merchants, on Thursday wrote on Twitter: "The law of transparency: proposing 'transparency' as a remedy is usually a substitute for actually doing something."

Indeed, what Facebook is pledging on election ads is still less than what the Honest Ads Act – which has bipartisan support in the U.S. Senate – would require of it. The bill would treat online ads like TV ads and require more reporting than Facebook's offering, such as: "a description of the audience the ad targets; the average rate charged for the ad; the name of the candidate/office or legislative issue to which the ad refers (if applicable); the contact information of the purchaser." It would also make Facebook, and really, all online platforms, liable to penalties and Federal Election Commission sanctions if it doesn't comply or lets an advertiser make false claims about itself or its ads.

Sen. Patrick Leahy questions witnesses during a Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime and Terrorism hearing titled ‘Extremist Content and Russian Disinformation Online’ on Capitol Hill, Oct. 31, 2017.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Lawyers for all three tech firms acknowledged their companies were aware of Russian and other foreign campaigns targeting American voters as early as 2015. That serves as confirmation for critics who have said the companies could have developed systems for fighting fake news and political frauds before the election – that it was a matter of will, not ability, that they didn't.

Queen's University computer science professor David Skillicorn, who specializes in the kind of artificial intelligence that the tech giants will likely have to use to identify bad actors such as terrorists and government agents, says the technical challenge is large but manageable.

"They really don't want to take responsibility for what they publish," he said. "[Their] position is: 'We'll generate the fewest possible rules we can get away with politically.' I don't think they have any principle behind that – this is purely pragmatism."

It is pragmatism, but it is also social media's unique business model. In the past, the companies that gathered the lion's share of the global advertising market – television, radio, newspapers, magazines – had to spend a significant percentage of that money creating content, while taking on legal responsibility for that content. For Facebook, the transaction is far more one-sided: it assumes most of the advertising revenue, while others provide the words, photos and videos – and assume most of the potential liability.

"The whole political discussion is opening up in terms of what's their responsibility for what they allow to spread or amplify," said Jason Kint, CEO of Digital Content Next, a trade association for 80 publishers, including The New York Times and Vox Media.

Facebook has made it clear that it will not meekly accept regulation that could hem it in. While the company has offered concessions to regulators in the form of greater transparency, it has also dramatically stepped up its lobbying efforts in the United States, spending $8.4-million this year on a team of 36 strategists who will push to allow the company to self-regulate, according to a report in The Wall Street Journal.

It is fighting to maintain a legal regime that is the "secret sauce" of its business, according to Mr. Kint. The set of legal protections known as "safe harbour" afford the company "very little to zero liability for what's on their platform," he said.

Facebook, and most websites in the United States that allow user-generated content, have argued for years that they are just platforms, not media companies, and therefore are not responsible for what gets published on their systems. This protection is spelled out in section 230 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1996; it includes a so-called "Good Samaritan" provision, which provides significant legal protection to websites, including Twitter and YouTube, that publish user-generated content.

"We might as well call it the internet cesspool act. It invites online services to look the other way," said Benjamin Edelman, an associate professor at the Harvard Business School who studies online markets. "It has been the subject of academic scorn and ridicule for two decades, but maybe the events of the past year will encourage Congress to revisit it."

Mr. Zuckerberg's views on the platform-publisher debate have been evolving since the election. He wrote in December, 2016: "Facebook is a new kind of platform different from anything before it. I think of Facebook as a technology company, but I recognize we have a greater responsibility than just building technology that information flows through."

But in a Sept. 27 Facebook post he included an implicit defence of safe harbour in which he suggested that criticism aimed at Facebook is, in fact, proof of its political neutrality. "Trump says Facebook is against him. Liberals say we helped Trump. Both sides are upset about ideas and content they don't like. That's what running a platform for all ideas looks like."

In October, Facebook chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg, speaking to U.S. news website Axios, affirmed that even so-called "fake news" and ads promoting it should be allowed on Facebook as long as a real person – and not a Russian spam-bot – is the one posting it.

"Sheryl Sandberg's comments show that Facebook is not going to change," said Jonathan Taplin, author of Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon cornered culture and undermined democracy.

"The only remedy is for regulators to revisit the safe harbour status that Facebook and YouTube operate under. The notion that they are incapable of policing their platforms is a fiction."

Mr. Edelman has argued that an update to laws is required – one that adds liability to "high-risk activities," including the functioning of advertising networks. This would require Facebook and other social-media platforms to do greater due diligence on all the advertising they accept – not just political ads – similar to how newspaper publishers or television broadcasters screen ads for things such as false claims.

Indeed, safe harbour is already under threat. In recent weeks, technology lobbyists have been negotiating with lawmakers to narrow the impact of a bill they believe could weaken the protection offered by safe harbour. The U.S. Senate Commerce Committee will vote next week on a bipartisan proposal that would make it easier to penalize operators of websites that facilitate online sex trafficking.

senate intelligence committee

Political power

While U.S. policy makers are grappling with how to deal with speech used as a political weapon on social-media platforms, there are other regulatory threats to Facebook's comfortable existence.

One of them comes as a result of shifting attitudes toward digital privacy in the European Union. Starting in May, 2018, the new EU-wide General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) comes into effect. Among other things, it will force marketers using privacy-sensitive data to seek explicit consent from its users before pushing some types of targeted ads into their Facebook feeds, with fines up to 4 per cent of a company's global revenue.

To understand the significance of this, it's important to grasp how and why Facebook has grown so quickly and become so profitable.

Facebook's powerful algorithms are designed to present stories, photos and videos that you just can't help but share with your friends. But they also help create an intricate profile of you as a Facebook user. Recent research by ProPublica found that there are more than 52,000 categories Facebook uses to microtarget ads at interests and desires users may not even know they have. Facebook's booming ad business shows that combination of precision and scale is compelling and lucrative. In its most recent quarter, Facebook reported there were more than six million advertisers a month bidding for our attention.

But not all of those categories are simple consumer preferences, such as "people who like gummy bears." Another ProPublica investigation found that Facebook enabled advertisers to target those interested in anti-Semitic and white supremacist messages.

How does Facebook's ad targeting work? Read our explainer.

The EU rules could throw some sand in the gears of Facebook's slick ad-targeting machine, by forcing users to "opt-in" before their personal data can be used in some of its most effective ad products, such as Custom Audience tools. "It has been a wildly popular product. Marketers match the e-mail addresses they have with e-mail addresses Facebook has" to target a company's existing customers and to help identify other potential customers, said Brian Wieser, an analyst with Pivotal Research Group. "It's hard to imagine Facebook getting permission from users to do that."

The new rules come at a time where Facebook's European ad business has been growing strongly, with ad revenues from small and medium-sized businesses growing 60 per cent year over year in the third quarter.

Mr. Wieser stands virtually alone among equity analysts with a sell rating on Facebook: He believes the company's current stock price doesn't fully take into account the downside risk of such regulations and their potential for slowing the company's jaw-dropping revenue growth.

While the company would not confirm which, if any, of its ad products will need opt-in, in a statement it said: "Facebook supports consistent data protection laws across Europe. Where applicable, we will of course adapt our existing practices to align with the GDPR."

Perhaps as much as €6-billion ($8.9-billion) in ad spending in Europe could be directly impacted by GDPR, according to Sean Blanchfield, CEO of Pagefair, an Irish company that helps marketers circumvent ad-blocker technology.

"The current tracking industry would have been considered dystopian sci-fi just 20 years ago," he said. "The consent requirements are very exacting. … Publishers and advertisers need to start working on the assumption that zero personal data (including IP addresses and personal cookies) can be used to target ads, except in a small minority of cases where users have agreed to it."

That said, he believes Facebook may be in a better position than most digital ad sellers. "Unlike nearly every other advertising platform, at least Facebook has a relationship with its users and can ask for consent."

Individual European countries are also taking action to control malicious online content. In June, Germany passed the Network Enforcement Act, which requires any social network with two million or more members to remove "unlawful" content (everything from incitements to violence to images of hate symbols) within 24 hours. The fines start at €5-million and can climb to €50-million. "Experience has shown that, without political pressure, the large platform operators will not fulfill their obligations, and this law is therefore imperative," Justice Minister Heiko Maas told reporters at the time.

senate intelligence committee

Mr. Wieser has argued that the costs of hiring humans to monitor user and ad content on a platform of more than two billion people may be higher than expected. In the Senate hearings, Mr. Stretch said that while Facebook has 10,000 employees dedicated to safety and abuse issues, it will double that by the end of 2018. Coupled with other capital investments in video, artificial intelligence and virtual reality, the increase in expenses could be 45 per cent to 60 per cent, Facebook said in this week's third-quarter financial report.

"This is substantially above our prior expectations," Mr. Wieser said in a research note. "Capital expenditures are expected to double next year (to $14-billion versus $7-billion for this year), also well above our prior expectations. These expenditures are likely to be higher than this level in subsequent years."

In Facebook's third-quarter earnings release on Wednesday, Mr. Zuckerberg turned those costs into a virtue: "We're serious about preventing abuse on our platforms. We're investing so much in security that it will impact our profitability. Protecting our community is more important than maximizing our profits." On a call with analysts he was even more direct: "I'm dead serious about this."

But even that may not be enough: In a disturbing but relevant parallel, in 2013 it was reported that the Chinese government employed two million people to run the internet censorship program for its online population; Facebook's still-growing user base is almost double China's total population.

Effective or overloaded?

Not all of Facebook's problems are political, though. Some of the large brand advertisers who provide its incredible profits are questioning whether it has all been money well spent. And some projections suggest the digital ad market is reaching saturation – that Facebook's incredible growth may be on the verge of slowing.

Another of Mr. Wieser's concerns is an issue that has been simmering since 2016: big advertisers questioning the effectiveness of ads on Facebook. "Marketers are increasingly scrutinizing their spending, and some are finding limited benefits from digital media," he wrote in a note published Oct. 12.

Brands such as Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV (with a $1-billion ad budget) and Procter & Gamble Co. ($2.4-billion) have publicly criticized Facebook, blasting confusing proprietary data and demanding third-party validation of ad effectiveness.

In February, the U.S. Media Rating Council announced it would perform an audit with Facebook to verify some of its metrics, though no timeline was announced and the results have still not been shared with advertisers. The MRC standard is that 50 per cent of display ads have to be "in view" for at least one second to trigger charging an ad buyer, while video ads need two seconds of viewership.

Facebook has also warned investors that it may soon reach peak "ad load" on its News Feed feature, that point where users see so many ads that it drives them off the platform. But it is expected to soon unveil new tools to help monetize its huge messaging businesses (Messenger and Whatsapp also have hundreds of millions of users) to keep revenue growth humming.

That said, Mr. Wieser agrees the risks he's outlining have not shown up in Facebook's numbers, yet.

Facebook's third-quarter earnings report saw revenue rise 47 per cent to a record $10.3-billion, above analyst expectations. Quarterly profit jumped 79 per cent to $4.71-billion, or $1.59 a share. Despite worries about ad load, advertisers drawn to mobile (88 per cent of ad revenue) and video continue to spend on the platform, and the average price per ad rose 35 per cent.

Facebook may be the No. 2 ad seller in the world, but its gross, operating and net margins are all better than those of Alphabet Inc., the world's No. 1 ad hawker. Its stock price has grown 60 per cent in the past year.

One final fly in the punchbowl is not something Facebook is doing wrong, but rather what it is doing so well: It cannot continue to grow its ad revenue as quickly as it has.

"The biggest issue limiting growth for Facebook (and for Alphabet) is that the faster the two companies grow, the sooner growth will converge with the rest of the advertising market," Mr. Wieser wrote in a research note on Wednesday.

According to eMarketer, since 2013 Facebook's advertising revenue has soared from $6.9-billion to a projected $38-billion in 2017. Over the same period, the year-over-year revenue growth rate has been spectacular but is finally slowing down – from 63 per cent in 2013 to 43 per cent in 2017. The projection by eMarketer suggests 2018 and 2019 may see growth closer to 20 per cent. By comparison, revenues for Google's more mature ad business went from $38-billion in 2013 to an estimated $72-billion in 2017 and never saw growth rates higher than 18 per cent.

"Digital advertising has grown so fast, but it doesn't cause the overall industry to grow faster than it was before. The crude math in the U.S. is maybe 3 per cent a year [for the total market]," Mr. Wieser said.

The last time Facebook faced such a dramatic set of challenges to its business model was during the transition from being a mainly desktop computer site to a mobile-first company. Its latest results showed 88 per cent of its ad revenue now comes from mobile.

This time, the entire tech industry faces the kind of global public and legal scrutiny not seen since the banking industry went through the wringer after the 2008 financial crisis. And unlike the mobile moment, it's harder to see how Facebook will turn this crisis into an opportunity.

Mr. Zuckerberg addressed his naysayers in the Wednesday investor call in a bold statement of intent: "We're bringing the same intensity to these security issues that we've brought to any adversary or challenge that we've faced."

And even Facebook's harsher critics don't think the company is in mortal danger, yet.

"I don't think we want to be naive here – they are in a position of dominance," Mr. Kint said. "It's the kind of dominance we've never seen by any company, and I don't see that changing significantly in the near future."